Open Source and DIY Permaculture Design

This is an open source and do-it-yourself permaculture design resource and tutorial. It is on the Geoff Lawton Permaculture Design Certification, Bill Mollison’s “Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual”, “Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture” by Sepp Holzer, and review of all of the content from Paul Wheaton’s Permaculture Design and Appropriate Technology Course Videos. All of these resources are highly recommended and links to each of them are in the resources section along with any others we’ve found useful. We discuss here the complete open source and DIY permaculture design process with the following sections:

- What is Permaculture

- Acknowledging Permaculture’s Founders

- Why Open Source Permaculture

- Ways to Contribute and Consultants

- Permaculture Design Details

- Permaculture Ethics, Principles, and Domains

- 3 Key Permaculture Ethics

- Permaculture Principles

- The Seven Domains of Permaculture Action

- Permaculture Design Process

- Step 0: Familiarize Yourself with the Process

- Step 1: Identify Needs and Assess Resources

- Step 2: Assess Site Through Observation and Research

- Step 3: Develop a Conceptual Design

- Step 4: Develop a Detailed Design

- Step 5: Implementation and Evaluation

- Open Source Final Detailed Permaculture Design (case study)

- Case Study Step 0: Familiarize Yourself with the Roots of the Permaculture Process

- Case Study Step 1: Identify Needs and Assess Resources

- Case Study Step 2: Assess Site Through Observation and Research

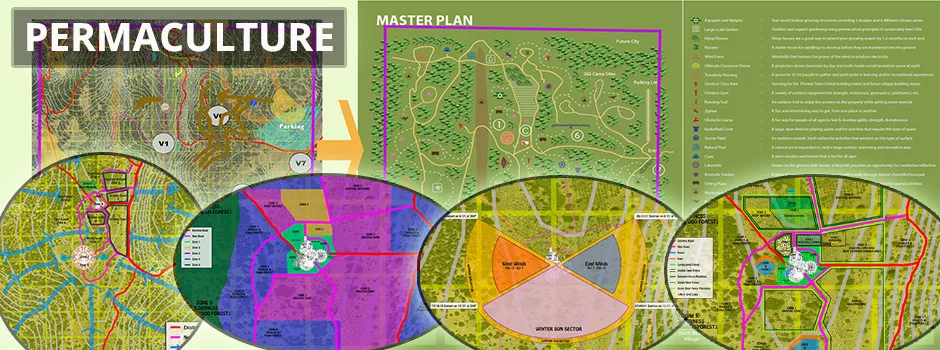

- Case Study Step 3: Develop a Conceptual Design

- Case Study Step 4: Develop a Detailed Design

- Resources

- Summary

- FAQ

RELATED PAGES (Click icons for complete pages)

WHAT IS PERMACULTURE

Permaculture is a design system that utilizes a set of principles and ethics that guides us to create holistic systems aiming to replicate nature. Observing nature within permaculture can be a path towards a paradigm shift of interconnected, regenerative closed-loop systems. Permaculture’s way of living and connected way of thinking focuses on the opportunities rather than obstacles. This moves us from a consumption mindset to a responsible and sustainable production alternative. At the core of this conceptual framework for sustainable development are 3 foundational ethics and 12 guiding principles that apply to all aspects of our existence and the decision making process – see Holmgren’s flower below.

Permaculture is a design system that utilizes a set of principles and ethics that guides us to create holistic systems aiming to replicate nature. Observing nature within permaculture can be a path towards a paradigm shift of interconnected, regenerative closed-loop systems. Permaculture’s way of living and connected way of thinking focuses on the opportunities rather than obstacles. This moves us from a consumption mindset to a responsible and sustainable production alternative. At the core of this conceptual framework for sustainable development are 3 foundational ethics and 12 guiding principles that apply to all aspects of our existence and the decision making process – see Holmgren’s flower below.

By using this as a ‘permaculture lens,’ we become earth protectors, people protectors, and fair-share/future care mediators. Using these 12 principles, we illuminate different perspectives and whole-systems thinking for design. This can address many of the most challenging issues of our generation while producing new opportunities.

In short, permaculture is about designing efficient and sustainable human settlements and preserving and extending natural systems. It models and integrates the successful strategies of nature and covers all aspects of settlement design from climatic factors, soils, housing, food, and energy to social, legal, economic design, and more. Ultimately, it is about ethical and intelligent stewardship as conscious and conscientious members of the natural systems that surround and support all life. When implemented properly, permaculture enriches all aspects of these systems sustainably and for the benefit of all people and life that interact with them. One Community calls this living and creating for The Highest Good of All.

ACKNOWLEDGING PERMACULTURE’S FOUNDERS

The term ‘permaculture’ was first coined by Bill Mollison and Mollison and David Holmgren in the mid-1970s. Permaculture was originally a contraction of ‘permanent agriculture’ and more currently has been expanded to ‘permanent culture.’ The concept of permaculture was born through questioning the mainstream trajectory of the way we live our lives, which had its rise in the environmental movement of the 1970s. David Holmgren planted the seed of permaculture through the exploration of the nexus between the design practices of landscape architecture, the holistic principles of science ecology, and the primary way we provide for human needs (agriculture). Bill Mollison has been the catalyst for spreading permaculture concepts to the world. Several books have been written on the topic, with the original being authored by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren entitled Permaculture One. Bill Mollison then went on to write Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, which is commonly used to teach courses. Several years later, David Holmgren wrote Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, also textbook-like presentation.

WHY OPEN SOURCE PERMACULTURE

Open sourcing One Community’s permaculture designs and processes supports and is part of our four primary goals. Our first and foremost goal is to demonstrate comprehensive sustainability covering food, energy, housing, and more. Second, to operate as an open source eco-tourism and teacher/demonstration hub that can be replicated as a sustainable living model. Third to provide and demonstrate food and lifestyle abundance beyond self-sufficiency and fourth to function as an educational example of comprehensive stewardship. This page will continue to develop with any additional resources we find helpful, input from consultants that choose to join our team and contribute, and the actual permaculture design implementation as part of the One Community Highest Good food, Highest Good society, Highest Good energy, Highest Good housing, etc. components. This will include the addition of pictures and our ongoing (indefinitely) experience with what worked, changes we made, evolutions in thought process, etc.

Open sourcing One Community’s permaculture designs and processes supports and is part of our four primary goals. Our first and foremost goal is to demonstrate comprehensive sustainability covering food, energy, housing, and more. Second, to operate as an open source eco-tourism and teacher/demonstration hub that can be replicated as a sustainable living model. Third to provide and demonstrate food and lifestyle abundance beyond self-sufficiency and fourth to function as an educational example of comprehensive stewardship. This page will continue to develop with any additional resources we find helpful, input from consultants that choose to join our team and contribute, and the actual permaculture design implementation as part of the One Community Highest Good food, Highest Good society, Highest Good energy, Highest Good housing, etc. components. This will include the addition of pictures and our ongoing (indefinitely) experience with what worked, changes we made, evolutions in thought process, etc.

“We cannot possibly imagine how abundant the world can be… it is way more abundant than we presently imagine.”

~ Geoff Lawton ~

WAYS TO CONTRIBUTE TO EVOLVING THIS SUSTAINABILITY COMPONENT WITH US

SUGGESTIONS | CONSULTING | MEMBERSHIP | OTHER OPTIONS

CLICK THESE ICONS TO JOIN US THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA

CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS COMPONENT:

Christopher Blair: GIS Technician/Horticulturist

Faisal Rasheed: Graphic Designer

Hakan Sabol: Certified Permaculture Designer, Wed Designer, Graphic Designer, and Video Editor

Jae Sabol: Certified Permaculture Designer, Project Manager, and Holistic Health Professional

Jennifer Lee: Graphic Designer (web design for this page)

Julia Meaney: Web and Content Reviewer and Editor

Maya Callahan: Sustainability Researcher

Pallavi Deshmukh: Software Engineer

Sangam Stanczak: Environmental Engineer (Ph.D., P.E.)

PERMACULTURE DESIGN DETAILS

Permaculture is a path to demonstrating what truly ethical and carefully planned land stewardship is capable of. When applied comprehensively, this approach can holistically integrate food, energy, housing, society, and economics as a complete stewardship model. It is regenerative and symbiotic with existing natural systems and provides living models that are healthier, happier, and long-term sustainable. We discuss this and more with the following sections:

Permaculture is a path to demonstrating what truly ethical and carefully planned land stewardship is capable of. When applied comprehensively, this approach can holistically integrate food, energy, housing, society, and economics as a complete stewardship model. It is regenerative and symbiotic with existing natural systems and provides living models that are healthier, happier, and long-term sustainable. We discuss this and more with the following sections:

- Permaculture Ethics, Principles, and Domains

- 3 Key Permaculture Ethics

- Permaculture Principles

- 1. Observe and Interact

- 2. Catch and Store Energy

- 3. Obtain a Yield

- 4. Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback

- 5. Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services

- 6. Produce No Waste

- 7. Design From Patterns to Details

- 8. Integrate Rather Than Segregate

- 9. Use Small and Slow Solutions

- 10. Use and Value Diversity

- 11. Use Edges and Value the Marginal

- 12. Creatively Use and Respond to Change

- The Seven Domains of Permaculture Action

- Permaculture Design Process

- Step 0: Familiarize Yourself with the Process

- Step 1: Identify Needs and Assess Resources

- Step 2: Assess Site Through Observation and Research

- Step 3: Develop a Conceptual Design

- Step 4: Develop a Detailed Design

- Step 5: Implementation and Evaluation

- Open Source Final Detailed Permaculture Design (case study)

- Case Study Step 0: Familiarize Yourself with the Roots of the Permaculture Process

- Case Study Step 1: Identify Needs and Assess Resources

- Case Study Step 2: Assess Site Through Observation and Research

- Observation and Research by Component

- Case Study Step 3: Develop a Conceptual Design

- Site Design Considerations

- Applying Permaculture Design

- Case Study Step 4: Develop a Detailed Design

- Final Design Plan

- Permaculture Implementation Process

- Before and After Photos

- What Worked and what We’d Recommend

- What We’d do Differently

- Costs and Yields

- Resources

- Summary

- FAQ

PERMACULTURE ETHICS, PRINCIPLES, AND DOMAINS

Permaculture is about designing efficient and sustainable human settlements and preserving and extending natural systems.

Permaculture design contains 3 ethics and 12 principles. We discuss here what each of these are, where and how they can be applied, and the design process itself. For easy reference, we’ve divided this information into the following sections:

- 3 Key Permaculture Ethics

- 12 Permaculture Principles

- The Seven Domains of Permaculture Action

- Initial Design Considerations (People Analysis and Assessment)

- Site Design Considerations (Site Analysis and Assessment)

- Applying Permaculture Design

- Design Concept Development Using Energy Flow

- Implementation & Evaluation

3 KEY PERMACULTURE ETHICS

The Ethics of Permaculture are compiled from the common thread among cultures that coexist with nature in a balanced manner, while applying lessons from modern times. There are three of them: Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share.

EARTH CARE

Earth Care is the key ingredient to sustaining life on Earth. This ethic places emphasis on supporting all life forms and in particular rebuilding soil, a natural capital that represents the overall long-term well-being of society. Soil is a living ecosystem. The soil is where all life begins and ends and it supports all life. The soil ecosystem is vital in sustaining plants, animals, and humans.

Earth Care means taking responsibility for, protecting and staying connected to the physical elements that are life giving – the things we could not survive without, for example soil, water, air, plants and pollinators such as bees. Humans are uniquely positioned to either continue damaging the earth (our home) or preserving it. Human action tends to be shortsighted – we are changing the world faster than we can see resulting consequences. The situation has become so adverse that geologists have named this era of heavy human influence the Anthropocene, which follows the Holocene, a geological epoch that lasted nearly 12,000 years. The problems of today are complex, yet the solutions remain simple.

PEOPLE CARE

People Care is the key ingredient to bringing about change that will ultimately secure a more fulfilling existence. This ethic calls for self-love, out of which grows intimate care for families, neighbors, and our wider communities. It also includes a recognition that greater wisdom results from collaboration. People Care at its core is about comradery, collaboration and peace. When there is a sense of belonging and community, it relieves the burden placed on meeting our needs through the fleeting satisfaction experienced through material goods. People Care naturally complements Earth Care because greater satisfaction and happiness is possible through connection, which puts less stress on the earth.

FAIR SHARE / FUTURE CARE

This third ethic supports the first two ethics. Future Care is derived from the Seven Generation Stewardship concept from Indigenous American teachings. This philosophy is based upon the idea that the decisions we make today should result in a sustainable world for seven generations into the future. This ethic calls for redefining what is enough and applying self-regulation towards our own consumption, and the consumption of the earth’s resources. Fair Share requires people to have an intuitive understanding of how much to give and how much to take. This is also often referred to as creating systems that return surplus, which can come in the form of time, fruits, healthy soil, wildlife, water, etc. This ethic requires us to apply common sense and to keep our desire to accumulate and overindulge in check.

PERMACULTURE PRINCIPLES

Permaculture principles are design principles that promote systems thinking, a holistic way to perceive all interactions with the world and our existence. These principles within permaculture have evolved since its inception. Bill Mollison left the principles up for interpretation and sprinkled them throughout his writings.

Holmgren clearly presents 12 Design Principles which appear to be inclusive, in some form, of the various lists available online and his principles apply to any kind of design, not just gardening or homesteading. Here is a fun song about the 3 permaculture ethics and Holmgren’s 12 principles.

Holmgren’s Design Principles are designed to be applied simultaneously and for all decisions. They are based on the modern science of ecology, specifically systems ecology. The principles, under the umbrella of the ethics, can be used as simple thinking tools to identify, plan, and evolve design solutions. The first six are from the perspective of elements and living beings, whereas the second six are from the perspective of the patterns and relationships that tend to emerge by system self-organization and co-evolution.

1. OBSERVE AND INTERACT

By taking time to engage with nature we can design solutions that suit our particular situation.

The principle of Observe and Interact reminds us to slow down, be aware, and truly engage with our surroundings, through reciprocal interactions for consciously and continuously evolving systems. This is also about introspection – looking within, as well as outward.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Observe and Interact”

2. CATCH AND STORE ENERGY

By developing systems that collect resources at peak abundance, we can use them in times of need.

The principle of Catch and Store Energy is about collecting resources when they are abundant and storing them for later use. This especially focuses on nearly infinite resources like the sun, rain and wind. It also applies to personal and communal progress – when motivation and energy are high, take action and make progress.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Catch and Store Energy”

3. OBTAIN A YIELD

Ensure that you are getting truly useful rewards as part of the work that you are doing.

The principle of Obtain a Yield is about making creative and wise decisions that result in responsible surplus. It is important to make choices that are expansive and long-term, choices that bring returns that are undying. This also extends to having energy to pursue what you love – having enough energy at the end of the day to pursue your passions and pleasures. This results in a positive feedback loop that amplifies the permaculture lifestyle.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Obtain a Yield”

4. APPLY SELF-REGULATION AND ACCEPT FEEDBACK

We need to discourage inappropriate activity to ensure that systems can continue to function well.

The principle of Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback applies at both the individual and global scale. It is our responsibility to take only what we need (keeping greed in check) and to be flexible and cognizant of our behavior, always striving to be better. At the global scale, it is important to be attentive of feedback and to adjust accordingly, prime example being Global Warming.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback”

5. USE AND VALUE RENEWABLE RESOURCES AND SERVICES

Make the best use of nature’s abundance to reduce our consumptive behavior and dependence on non-renewable resources.

The principle of Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services reminds us to take action that maximizes long-term returns, while minimizing consumables and single-use types of operations.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services”

6. PRODUCE NO WASTE

By valuing and making use of all the resources that are available to us, nothing goes to waste.

The principle of Produce No Waste calls to see everything as a resource. Putting value on everything and finding creative ways to refuse, reduce, reuse, repair, repurpose or upcycle, recycle, and finally rethink. Bill Mollison’s definition of a pollutant is “an output of any system component that is not being used productively by any other component of the system.”

Here’s a fun song that explains “Produce No Waste”

7. DESIGN FROM PATTERNS TO DETAILS

By stepping back, we can observe patterns in nature and society. These can form the backbone of our designs, with the details filled in as we go.

The principle of Design From Patterns to Details is a natural outcome of the application of the principle of Observe and Interact – pattern recognition. This principle reminds us to always keep the big picture in mind and to be cognizant of the long-term overall impacts of our actions, our choices, and designs. When designing, it is important to step back and observe the patterns in nature and society, where society represents human evolution – how well we have adapted to our surroundings. This icon used for this principle, spider on its web, directly represents zone and sector site planning – most widely used concept of permaculture design.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Design from Patterns to Details”

8. INTEGRATE RATHER THAN SEGREGATE

By putting the right things in the right place, relationships develop between those things and they work together to support each other.

The principle of Integrate Rather Than Segregate highlights the importance of working together as a society because we can go further together. This also applies to all aspects of our existence – looking at all aspects of our lives in an integrated, interconnected manner. All elements are designed to be interconnected (have a relationship), both serving and supporting multiple functions within the whole system.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Integrate Rather than Segregate”

9. USE SMALL AND SLOW SOLUTIONS

Small and slow systems are easier to maintain than big ones, making better use of local resources and producing more sustainable outcomes.

The principle of Use Small and Slow Solutions helps to prevent permanent damage, or time wasted in cleaning up an unforeseen mess due to haste and lack of foresight. Smaller and slower systems are more manageable in terms of maintenance, while simultaneously creating space for creative, more sustainable decisions along the way.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Use Small and Slow Solutions”

10. USE AND VALUE DIVERSITY

Diversity reduces vulnerability to a variety of threats and takes advantage of the unique nature of the environment in which it resides.

The principle of Use and Value Diversity is key to security. Diversity offers insurance against unpredictable variations in the natural environment. Diversity is valuable in reducing vulnerability within the natural fluctuations that we live in. Also, a diverse society is more stable and a more effective think tank.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Use and Value Diversity”

11. USE EDGES AND VALUE THE MARGINAL

The interface between things is where the most interesting events take place. These are often the most valuable, diverse and productive elements in the system.

The principle of Use Edges and Value the Marginal reminds us to be creative in our thinking and to question the norm for the possibility of something extraordinary. This also reminds us that everything has value, even the things that appear initially as marginal or unconventional. If we stopped cutting the forests down now and left it to perform its essential functions for the larger biosphere, the earth could recover. The permaculture lifestyle calls for us to transform the land that is marginal and make it productive.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Use Edges and Value the Marginal”

12. CREATIVELY USE AND RESPOND TO CHANGE

We can have a positive impact on inevitable change by carefully observing, and then intervening at the right time.

The principle of Creatively Use and Respond to Change is directly linked to our very survival. Charles Darwin said, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, not the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Humans are unique in the evolutionary process because we have more input in our survival through creative adaptation than other living beings. Other living beings are reliant on random opportune events that give them an advantage, but humans, for the most part, can be deliberate in our survival. The only constant in life is change – nothing is for certain. So instead of resisting the inevitable, it is important to embrace, accept, foresee, and be prepared for change. Change brings lots of positives, often little pockets of blessings in disguise. This principle calls on being flexible, going with the flow, and improvising along your journey. This also links us back to Principle 1: Observe and Interact, because we must be able to see things not only as they currently are, but also as they will be in the future.

Here’s a fun song that explains “Creatively Use and Respond to Change”

THE SEVEN DOMAINS OF PERMACULTURE ACTION

The Seven Domains of Permaculture Action are where we apply the ethics and principles of permaculture. These seven domains are radical in a sense, calling for substantial revisions to how we currently exist and are central to a more sustainable and just society. They call upon us to transform from being passive recipients to participants. This process starts with ourselves, and spirals outward to include families, communities, and eventually all life. Weaving the seven domains together with a backdrop of the foundational ethics and principles has the potential to create a holistic, all-inclusive, and completely sustainable civilization.

Here is a 2.5-minute audio of David Holmgren talking about the seven domains | source

The icons below each domain also link to what we consider as One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to each one.

LAND AND NATURAL STEWARDSHIP

The domain of Land and Nature Stewardship is what most people think of when they hear ‘permaculture.’ It includes all elements having to do with working nature to obtain long-term, responsible yields. Some real-world examples include regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, biointensive gardening, forest gardening, organic agriculture, holistic rangeland management, integrated aquaculture, and wild harvesting and hunting. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Land and Nature Stewardship include the following:

BUILDING

The domain referred to as ‘Building’ covers all infrastructure and emphasizes constructed elements built to last, while honoring land and nature stewardship and enhanced living. Some real-world examples include solar design, natural construction materials, water harvesting, waste reuse, biotecture, earth sheltered construction, and natural disaster resistant construction. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Building include the following:

TOOLS & TECHNOLOGY

The domain of Tools and Technology covers human ingenuity and how it can be used in a creative and resourceful way – a way that preserves foresighted survival and current comforts. Some real-world examples include recycling, fuels from organic wastes, and renewable energy. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Tools and Technology include the following:

EDUCATION AND CULTURE

The domain of Education and Culture covers the way we teach and the way we function and define culture – striving towards a more flexible, active and creative way of learning and existing among one another. Some real-world examples include social ecology, home schooling, Waldorf education, participatory arts and music, action learning, and transition culture. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Education and Culture include the following:

HEALTH AND SPIRITUAL WELL-BEING

The domain of Health and Spiritual Well-Being encompasses taking more responsibility for personal well-being through preventative care methods and extends to dying with dignity and mental well-being. Some real-world examples include alternative medicine, home birth and breastfeeding, dying with dignity, and body/mind/spirit disciplines. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Health and Spiritual Well-Being include the following:

FINANCE AND ECONOMICS

The domain of Finance and Economics strives to encourage the development of a more robust, stable, and sustainable economy. Some real-world examples include ethical investment and fair trade, farmers markets and community supported agriculture, tradable energy quotas, and ecological living. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Finance and Economics include the following:

LAND TENURE AND COMMUNITY GOVERNANCE

The domain of Land Tenure and Community Governance encourages a more communal existence, honoring our social nature as humans and the ingrained desire to co-exist. Some real-world examples include: native title and traditional use rights, cooperatives and body corporates, and co-housing and ecovillages. One Community’s most relevant open source contributions to the domain of Land Tenure and Community Governance include the following:

PERMACULTURE DESIGN PROCESS

Several permaculture design processes can be used when implementing a permaculture-based design. Each step is informed by the previously mentioned ethics and design principles that lead to sustainable, designed-to-last, and regenerative solutions. Interestingly, the end product of the design process is all but a starting point. The true design happens when the design is put into action and you engage in an evolutionary process that calls for adjustments along the way. The design process described here is a good starting place to kickstart the long-term progression and transformation that naturally occurs through feedback and a desire to steer towards efficiency and common sense. Approach the process with confidence. The aim is not perfection, but rather a deliberate and conscious engagement in a journey with the sole goal to make things better and better over time.

The Design process is comprised of the following overarching steps:

- STEP 0: Familiarize Yourself with the Process (optional)

- STEP 1: Assess Resources and Identify Needs

- STEP 2: Assess Site Through Observation and Research

- STEP 3: Develop a Conceptual Design

- STEP 4: Develop a Detailed Design

Note: William Horvath eloquently brings together the details from many known contributors of Permaculture and we recommend his resource that can be found here and this flow diagram that distills the overall process. Our information in this section draws most heavily from this information and Geoff Lawton’s Permaculture Design Course. A broad diversity of other resources were then used to confirm and support this information, but to a much lesser extent. We’ve included the most significant of them within the content and in the resources section.

STEP 0 – FAMILIARIZE YOURSELF WITH THE PROCESS

The design process is best initiated by familiarizing yourself with the permaculture concepts with the intent to keep these in the forefront while going through the design, implementation, and adaptive experience. The 3 foundational ethics and 12 guiding principles can be written on index cards so this information remains at your fingertips – as pictured below:

In this way, the ethics and principles become the backbone of all decisions, big and small:

- EARTH CARE: I pledge to preserve and protect the water, air, soil, plants and pollinators – all baseline life-giving elements.

- PEOPLE CARE: I pledge to care for self, family, neighbors, and the wider community. I recognize the potential for greater wisdom through collaboration, peace, and a secure sense of belonging.

- FAIR SHARE: I pledge to redefine what is enough, keeping my desire to accumulate and overindulge in check.

- OBSERVE AND INTERACT: I am reminded to slow down and genuinely engage with, learn, explore, document, and improve my internal and external landscapes.

- CATCH AND STORE ENERGY: I am reminded to hold ‘boundless’ and retainable energy within the system I live in for as long as possible, slowing down the entropic process.

- OBTAIN A YIELD: I am reminded to produce only long-term, efficient, and responsible surplus, both monetary and non-monetary.

- APPLY SELF-REGULATION AND ACCEPT FEEDBACK: I am reminded to take only what I need and consciously keep that in check. I create self-regulating systems and make adjustments from the feedback.

- USE AND VALUE RENEWABLE RESOURCES AND SERVICES: I am reminded to have each element within the system I live contribute to other elements, as well as receive from other elements to thrive.

- PRODUCE NO WASTE: I am reminded that everything is a resource and to rethink the concept of waste through reduce, reuse, repair, repurpose or upcycle, and recycle.

- DESIGN FROM PATTERNS AND DETAILS: I am reminded to apply natural ecosystem mimicry.

- INTEGRATE RATHER THAN SEGREGATE: I am reminded to think with diversity and multifunctionality in mind.

- USE SMALL AND SLOW SOLUTIONS: I am reminded to work at a pace that allows me to see my impact to prevent permanent damage.

- USE AND VALUE DIVERSITY: I am reminded to use diversity to reduce vulnerability against unpredictable variations in the natural environment.

- USE EDGES AND VALUE THE MARGINAL: I am reminded to look for often invisible advantages and functions and improve unproductive areas.

- CREATIVELY USE AND RESPOND TO CHANGE: I am reminded of what Charles Darwin said, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, not the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”

STEP 1 – IDENTIFY NEEDS AND ASSESS RESOURCES

Identifying your needs and assessing your resources is an important step prior to beginning the permaculture-based design process (or any large design or construction project for that matter). It is helpful to gather key information and assess your resources and commitment to the process by identifying your needs (or design criteria) and objectively assessing the resources available to you. Step 1 is to organize your talents and engage in a cooperative process that is centered around being ethically responsible and accountable. People with a desire to make a difference and are willing to invest the necessary energy are the only true resources needed to bring about harmony and restore the very forces that keep us alive – air, water, and land.

IDENTIFY YOUR NEEDS

Identifying your needs or design criteria helps get clear on the intent of your design. This is called the “Design Brief” and should include the intended use and priorities of the property, the level of food self-sufficiency desired, who and how many people will live there, and an overview of anything else relevant to the design. Having a clear vision and goals speeds up both the design and implementation process. Toby Hemenmay says the following regarding envisioning your future, “The visioning phase begins with a no-holds-barred brainstorm, limited to some degree by finances and really only by ecological and ethical constraints.” During this step clearly articulate your goals – this is a foundational step of the design process.

ASSESS YOUR RESOURCES

Objectively assessing the resources at hand is essential to your success. The design process requires research, time, and problem-solving skills. Implementation requires deeper research, considerably more time, patience, observation skills, flexibility, and complex problem-solving and adaptation skills. The larger the project, the more people will be involved. This means the addition of quality management and people skills. Larger sized projects may require greater financial investment as well.

A resources and limitations analysis is useful to accomplish this step and entails listing your personal resources and limitations to identify areas of abundance and scarcity. During this step, assess your time, budget, skills and other aspects that may be limiting factors to execute your endeavor. Knowing yourself is key, because you can only build on your strengths. As said by Aristotle, “knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.”

It is extremely important to consider your ability and dedication to the entire process before you start. What is your track record of success with similar-sized projects and commitments? What are your strengths and weaknesses and what are you able and willing to lose if it fails? What new skills will you need to learn and what skills will you need help with? Are you the person to lead the project implementation or would someone else be better suited for that?

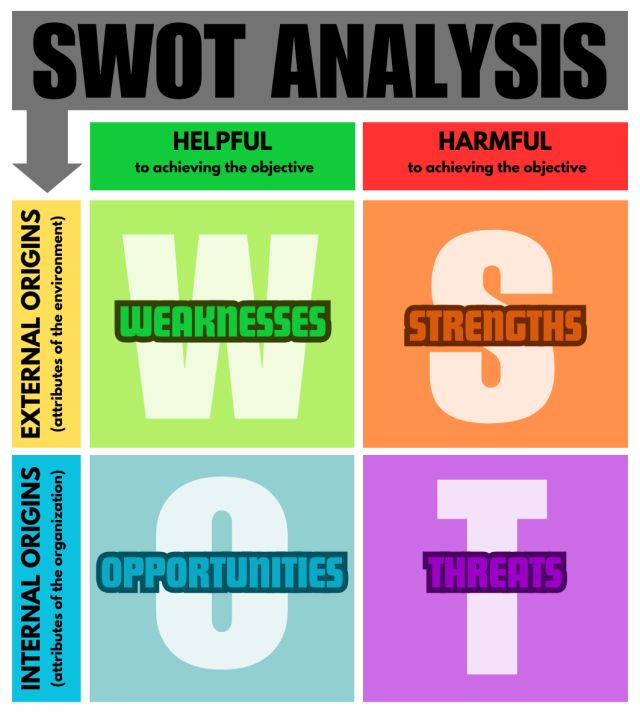

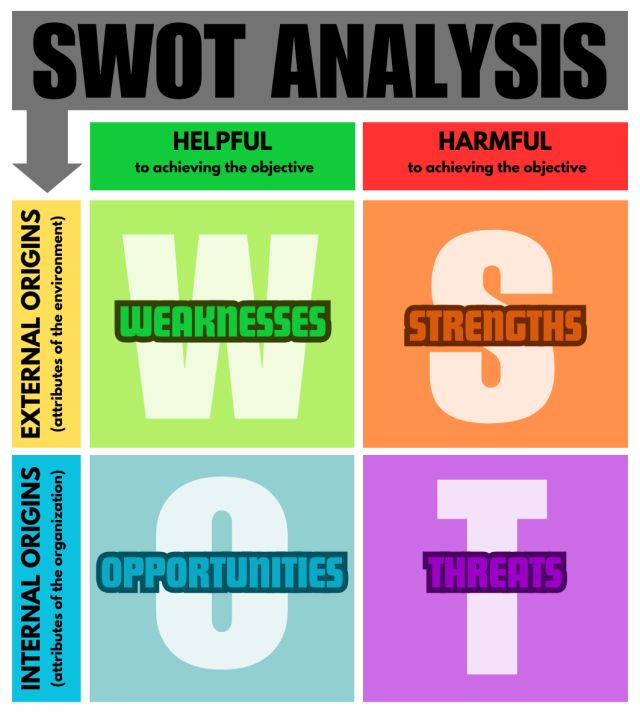

If you haven’t already, conducting a SWOT analysis would be a good thing to do before starting. If you need help, this Wikipedia page that teaches the process. The image below shows an overview of what the process is and clicking on the image allows you to download an editable version of the table that you can complete for your project. This is a view-only file, so please create your own copy of this template to edit by clicking File > Make a copy…

Once completing this table, which entails listing the team and project strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, the next step is to come up with the following strategies:

- OPPORTUNITY – STRENGTH: Strategies to use strengths to take advantage of opportunities

- OPPORTUNITY – WEAKNESS: Strategies to overcome weaknesses by taking advantage of opportunities

- THREAT – STRENGTH: Strategies to use strengths to avoid threats

- THREAT – WEAKNESS: Strategies to minimize weaknesses and avoid threats

STEP 2 – ASSESS SITE THROUGH OBSERVATION

Step 2 is to assess your site through observation and research. During this step, the goal is to collect information that is potentially relevant to the design process. This step has two components. The first is observation – ideally making direct observations in the field for an entire year – learning where the sun shines, shadows cast, wind blows, water flows, water collects, pollution drifts, and the such. The second is research – gathering characteristics that were not observed directly. Research uses off-site resources, such as books, local experts, and the internet. These two components ultimately inform our choices to create an effective permaculture design.

OBSERVE AND DEVELOP A BASE MAP

Before you go to your site for the observation phase, make a basemap. The basemap provides a framework for your design. The basemap should at a minimum have your property boundaries, along with a scale and compass rose. You can consult your local municipality or use an online mapping tool to define the property line. Online mapping tools include: Google Earth, Google Maps, Bing Maps Bird’s Eye View, Topographic Maps on Google Earth, Area Calculator, Topographic National Map Download, GPS Visualizer: Assign elevation data to coordinates, Creating Contours using ASTER DEM and Global Mapper | MacOdrum Library and MyTracker App.

Google Earth is a powerful, free program that can be used to learn about the property and get an overall picture of your property and the surrounding area. Take time to look at the many features offered to familiarize yourself with the property: historical maps, distance to the ocean, altitudes, compass aspect, terrain, contours.

If possible, get contours on your basemap to help with understanding the terrain. Contour lines give essential information, such as how the land slopes, which impacts sun energy exposure and water travel. Darren Doherty provides this tutorial we think is pretty good for how to create a boundary in GoogleEarth:

Click here to view Darren Doherty’s tutorial

He also has an article on Making Contour Maps on the Cheap, which suggests having elevation data about every 1 foot. A visual terrain of your property may also be available using Google Maps’ terrain view. If using Google Earth,”World_Topo_Map (MapServer)” may be of assistance. Topographical data is also available in online viewers, such as through ArcGIS, National Map Viewer, ESRI’s World Topographic Map Viewer, Mapping Support, My Topo, and Contour Map Creator.

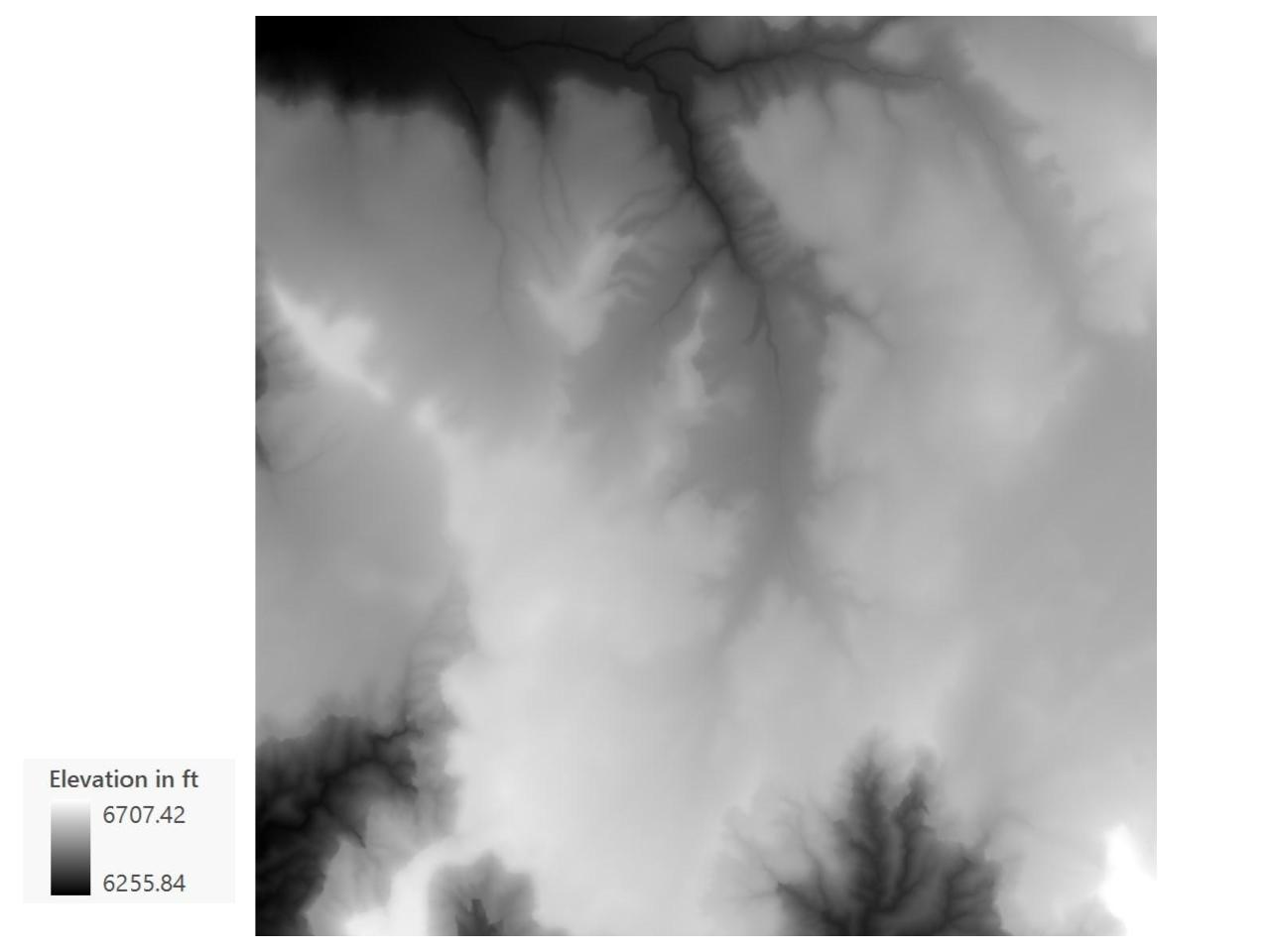

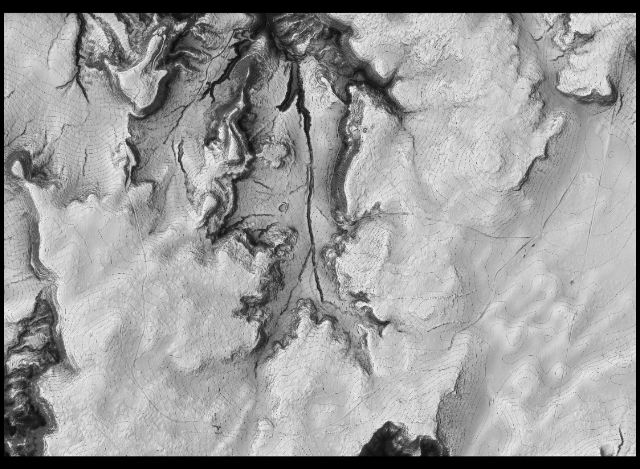

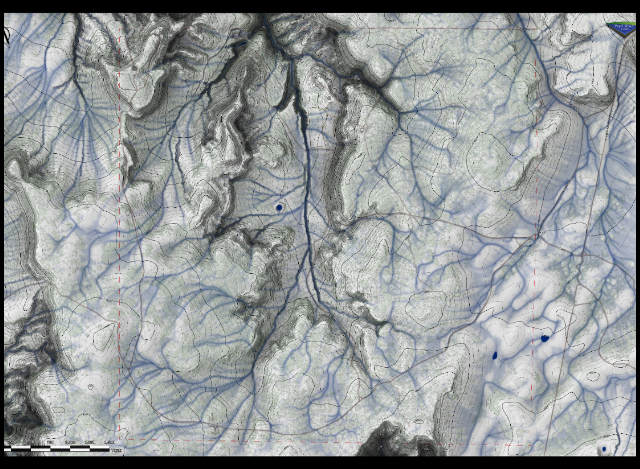

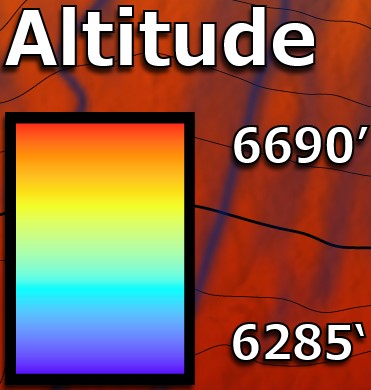

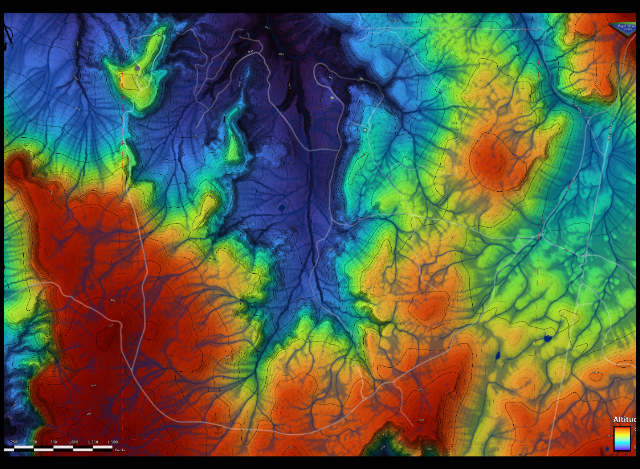

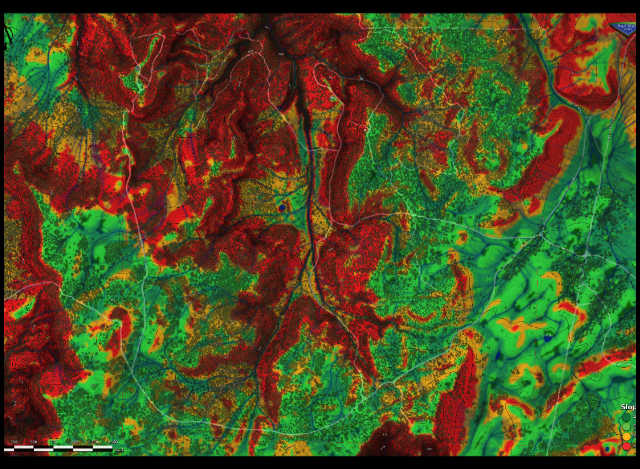

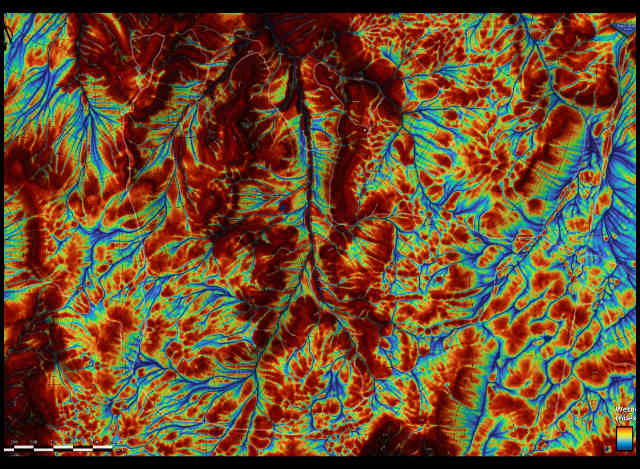

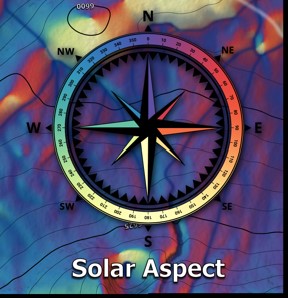

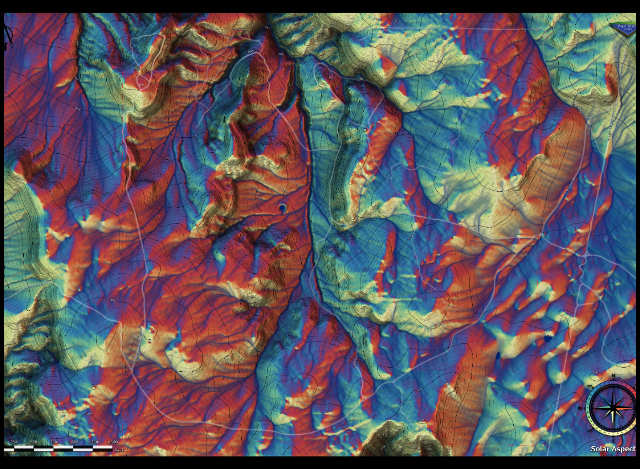

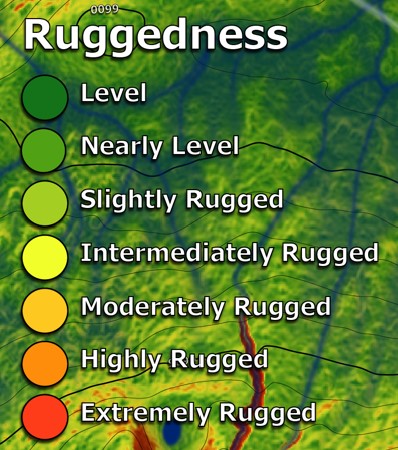

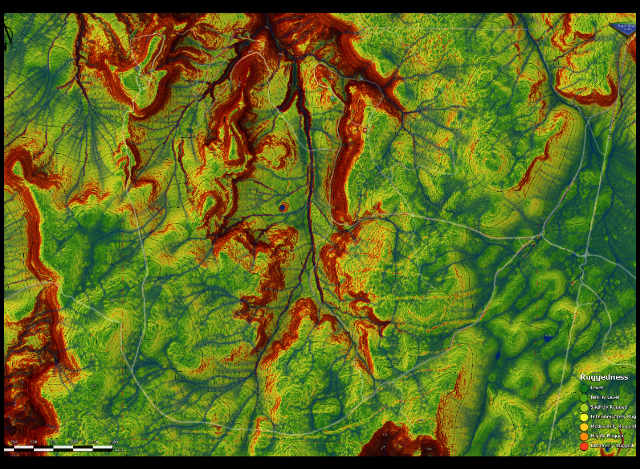

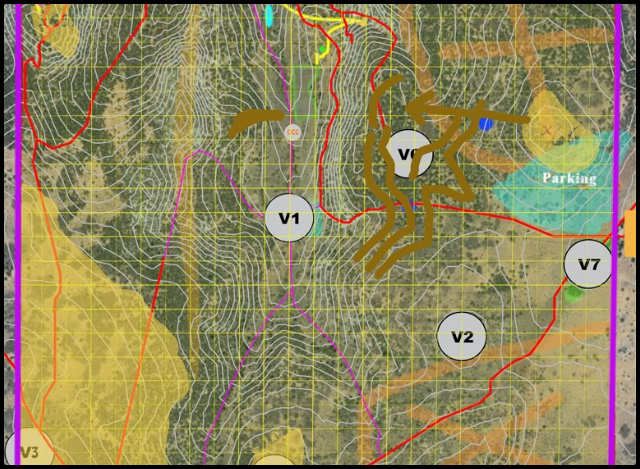

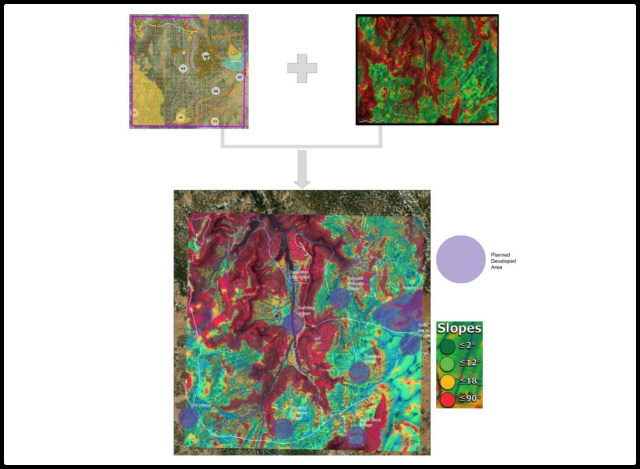

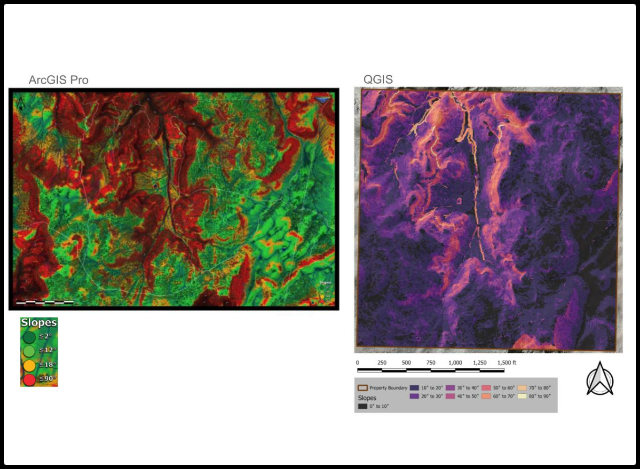

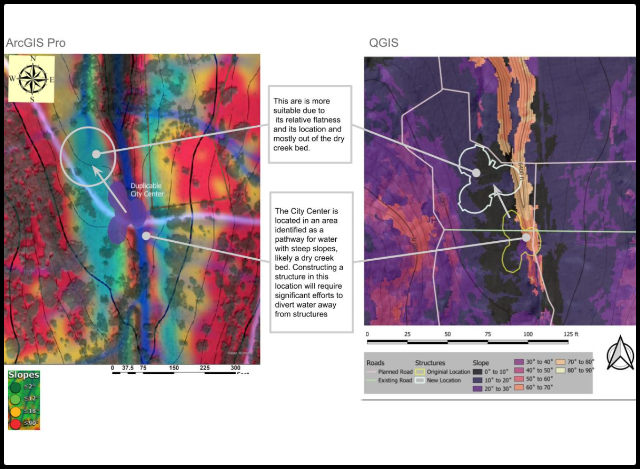

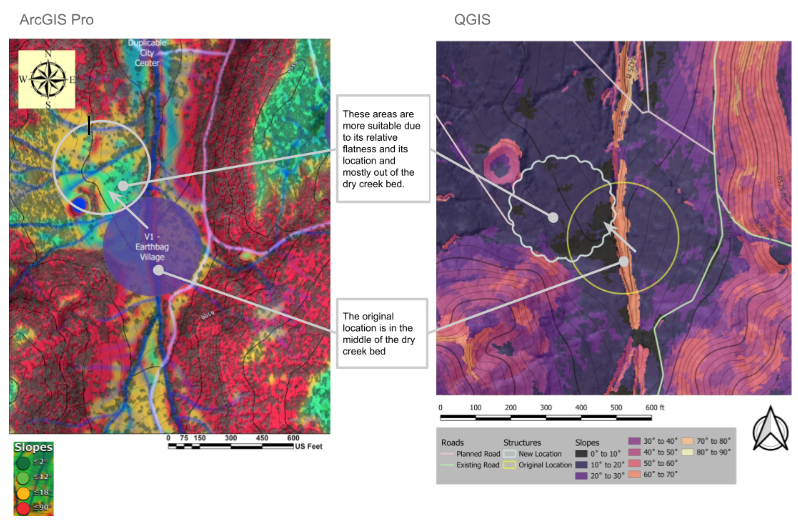

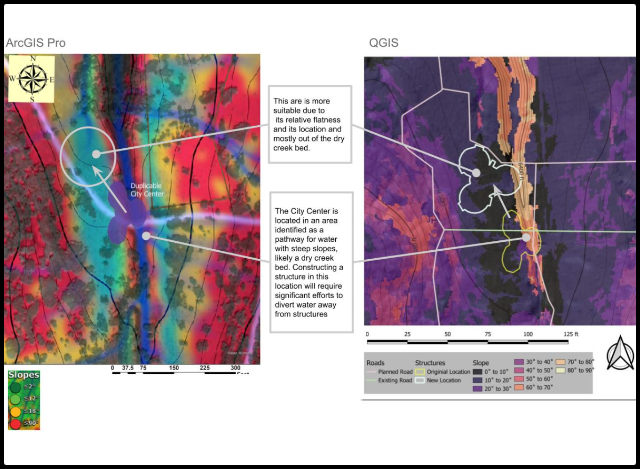

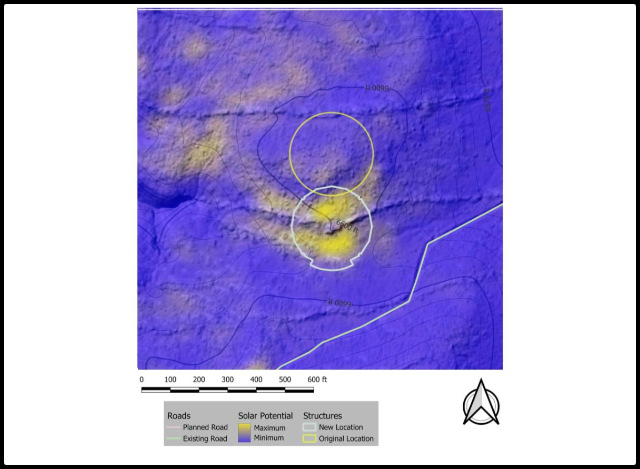

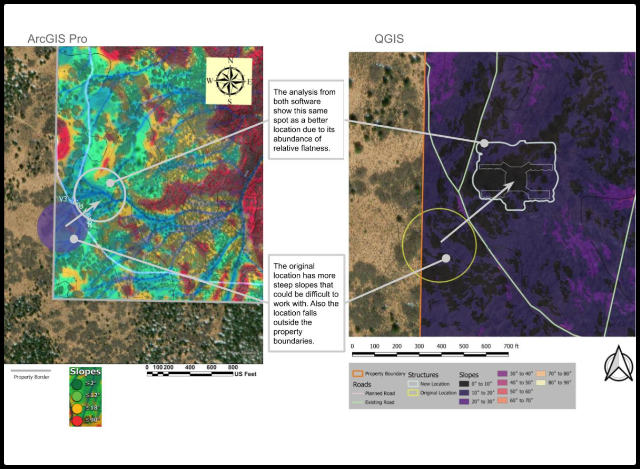

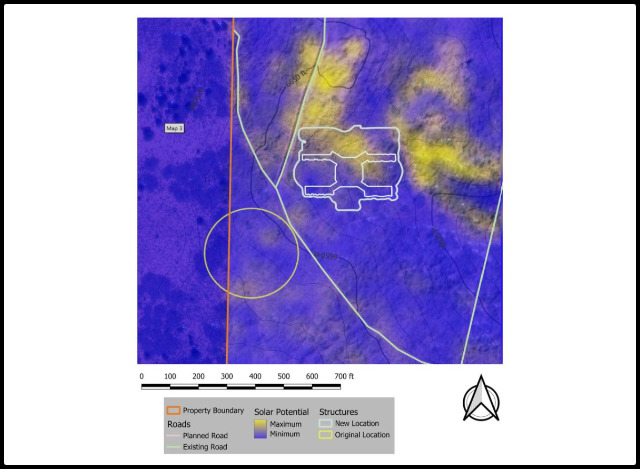

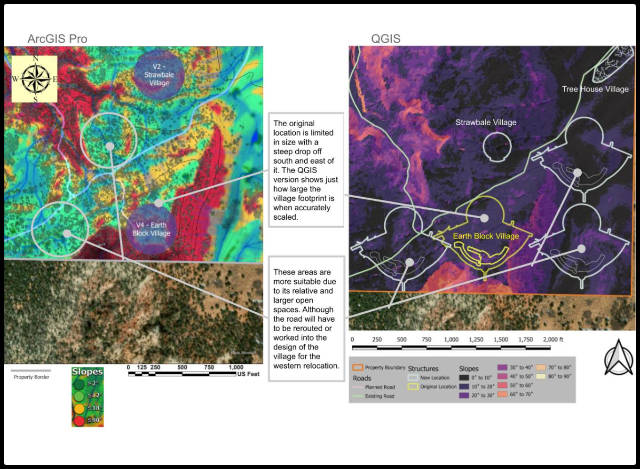

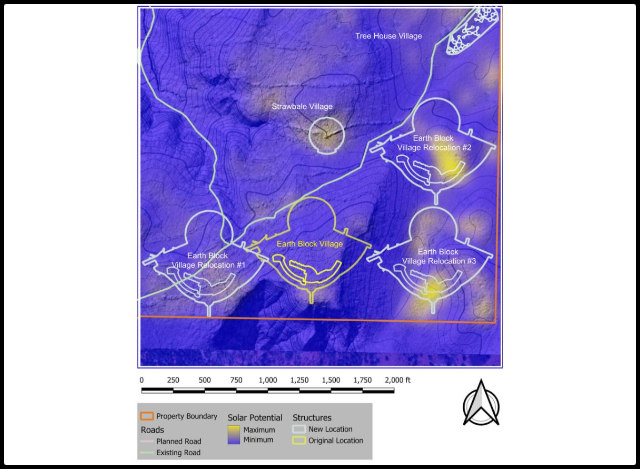

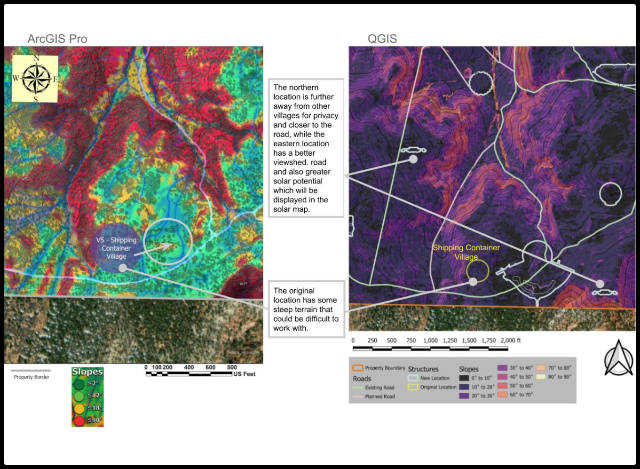

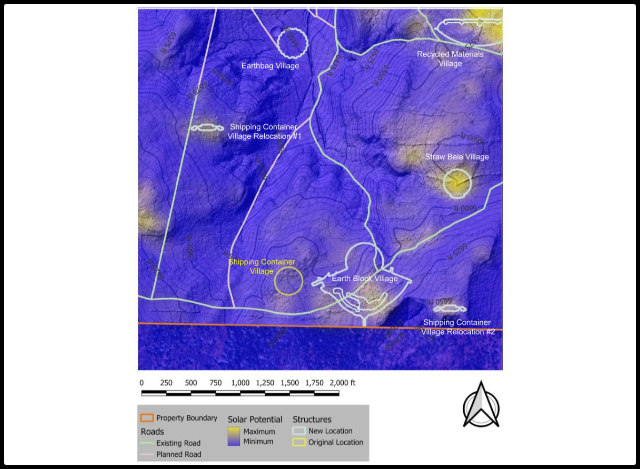

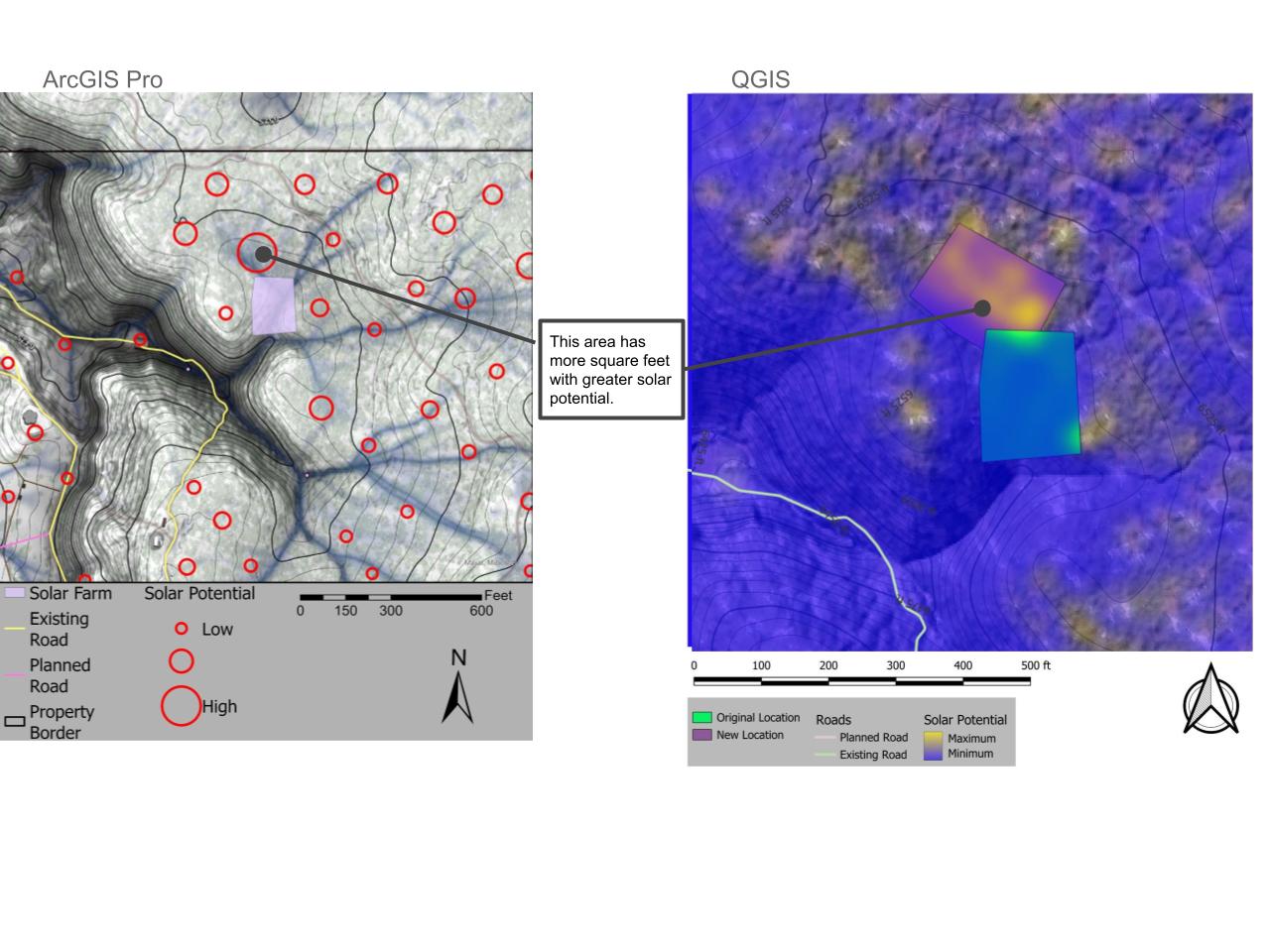

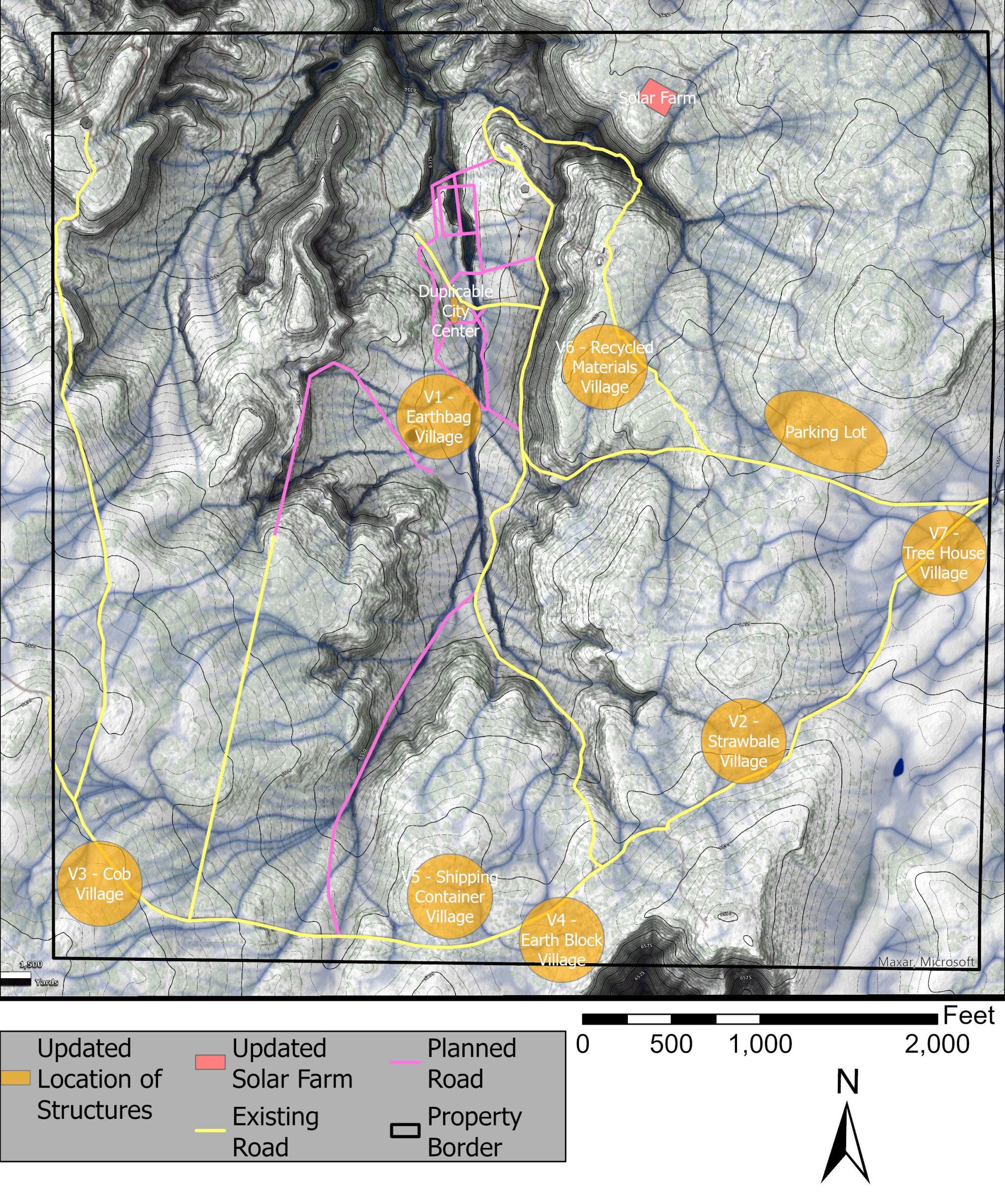

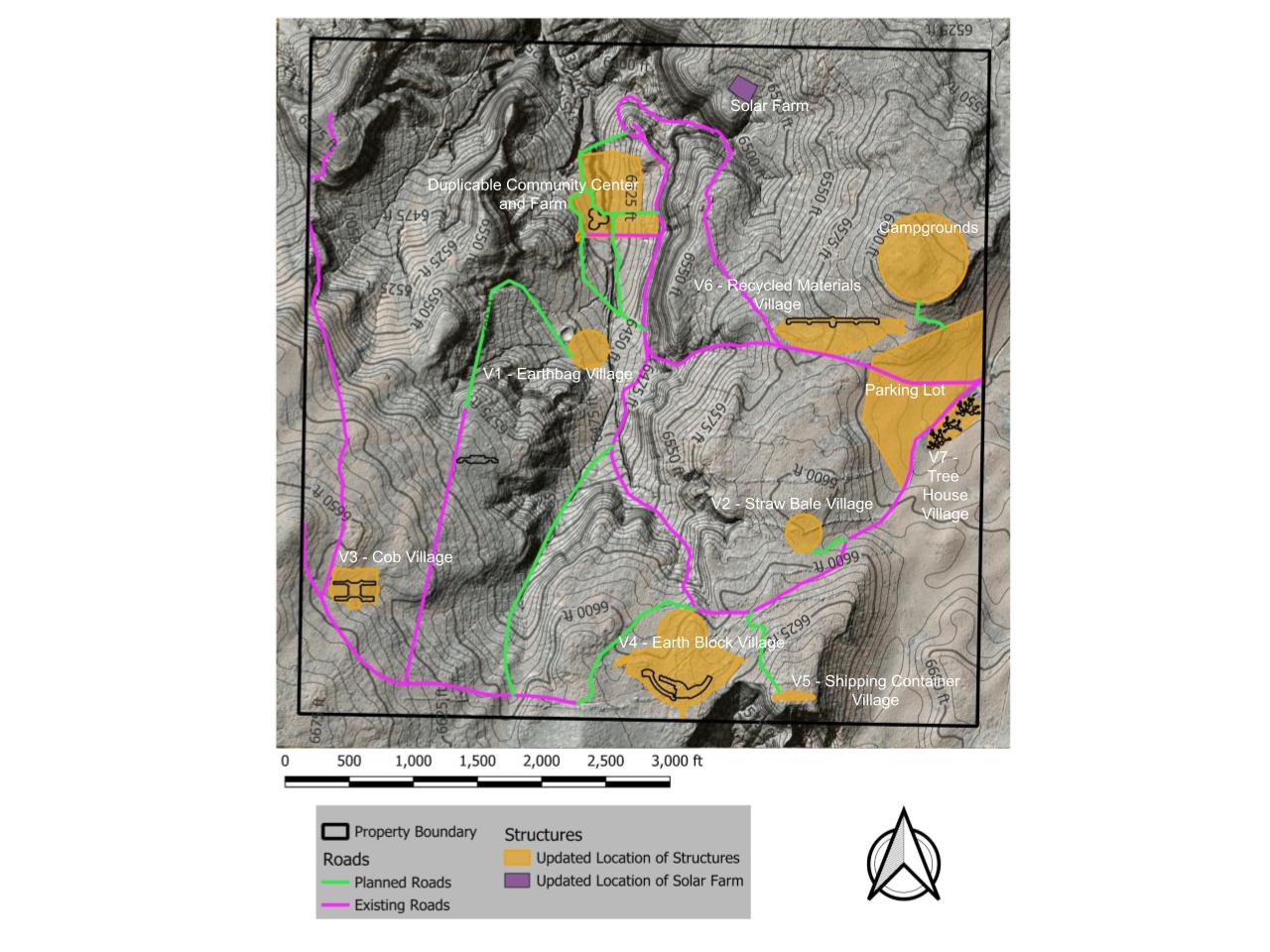

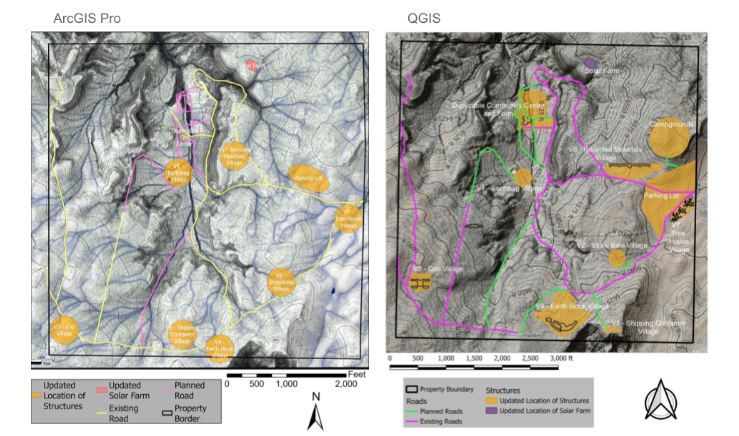

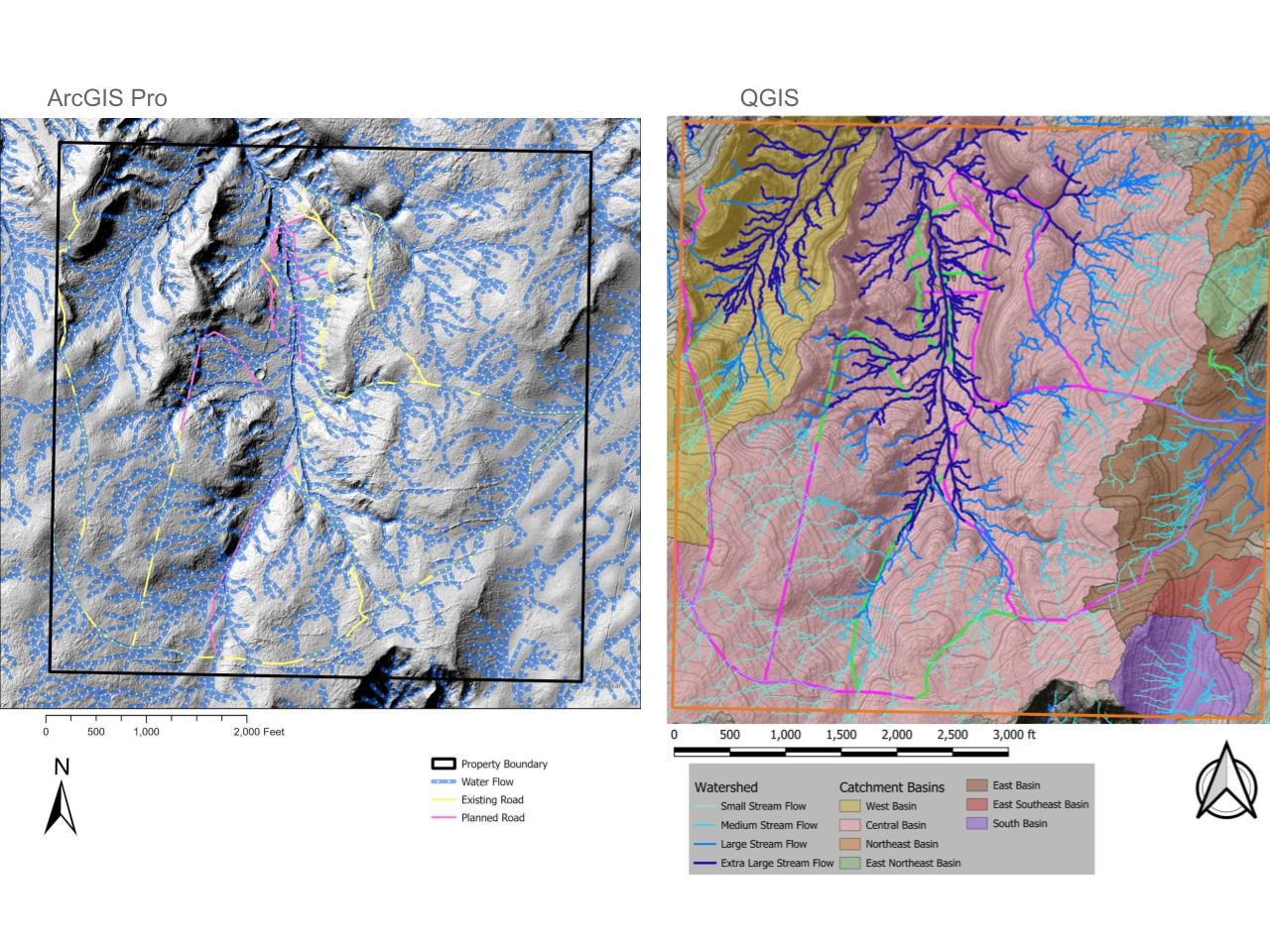

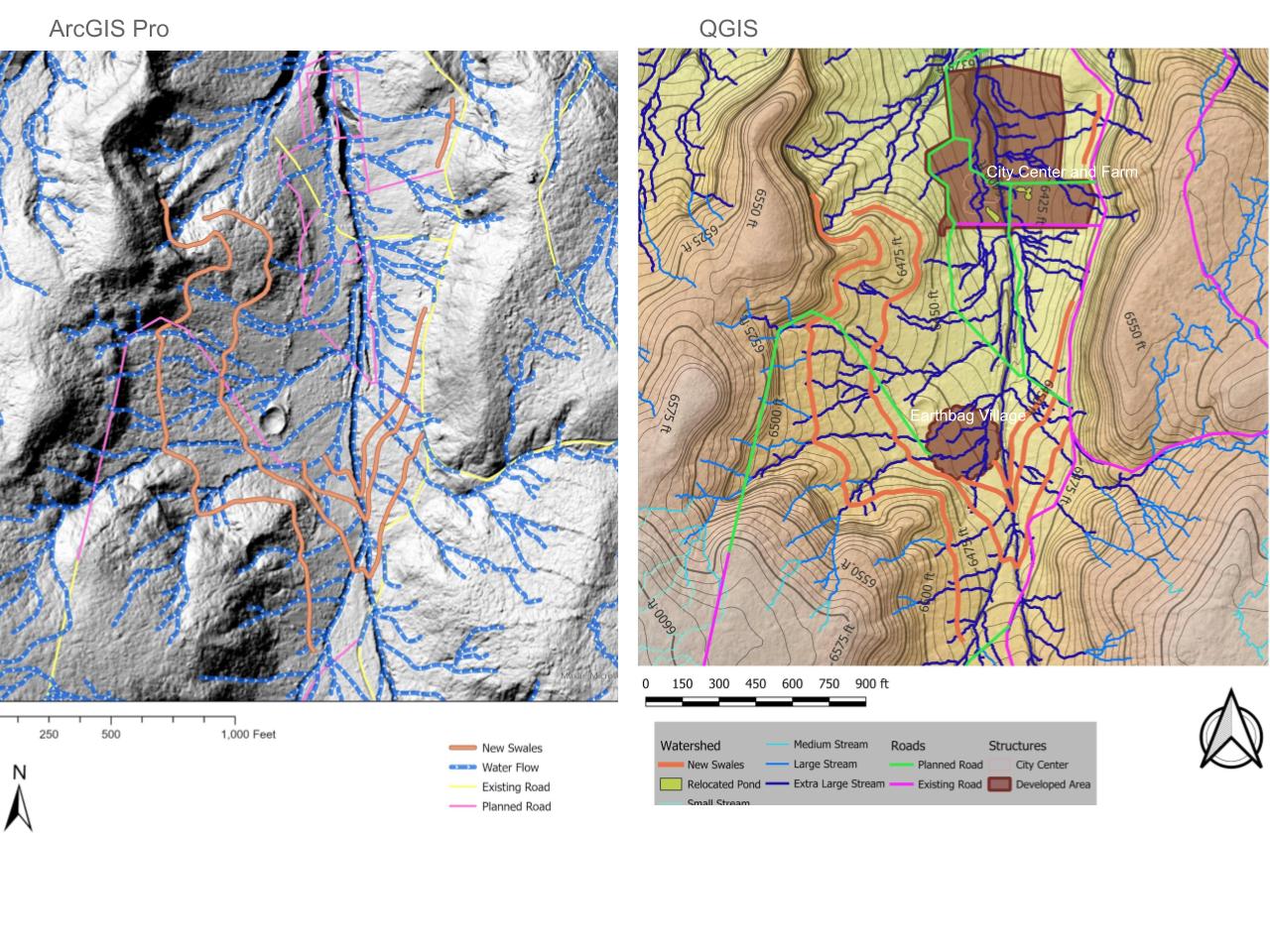

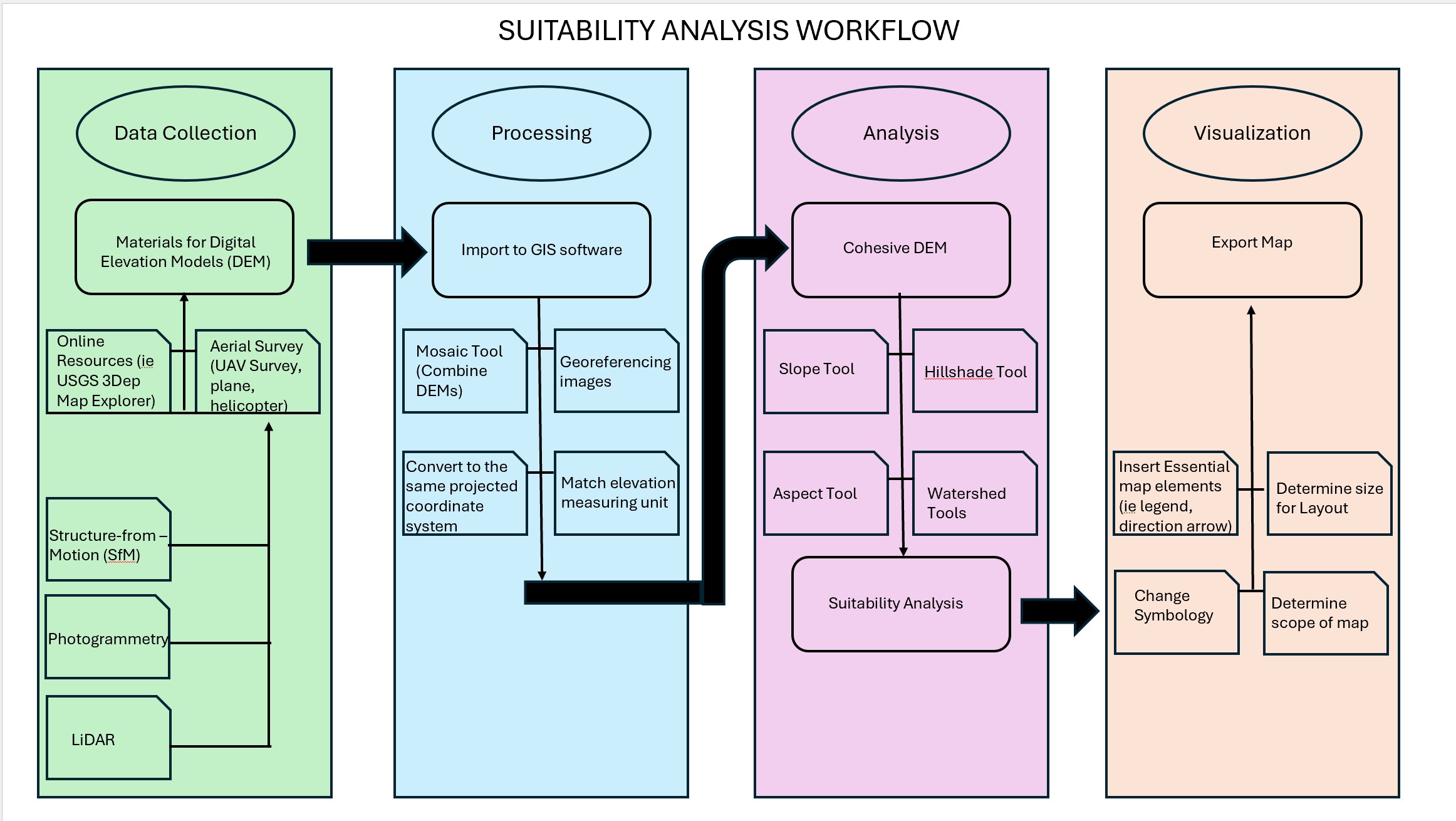

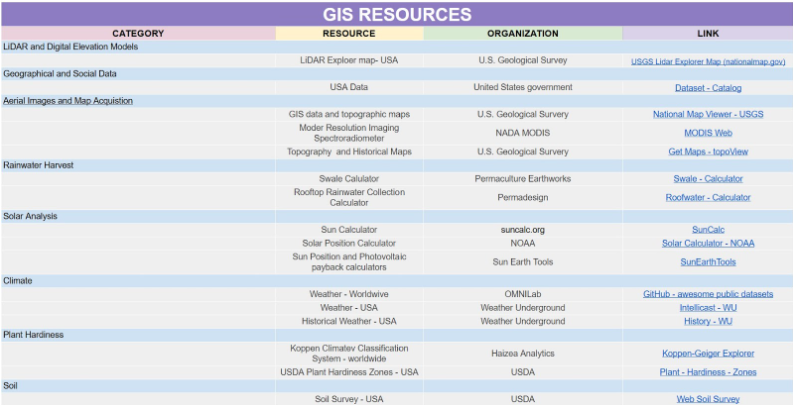

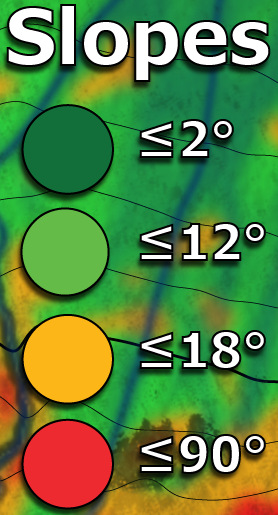

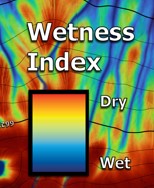

A more detailed approach to viewing the landscape and producing a more accurate basemap is to use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software. With GIS software, contour lines can be generated at any interval, and it can display the landscape’s slope degrees, the cardinal direction it faces (aspect), and the shadows cast by the topography (hillshade) at different times of the day. This is all based on data from aerial surveys that produce Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), which can often be acquired online for free. Much of the United States has been surveyed, and DEMs – some as detailed as 1 square meter or even finer – can be found on the USGS Lidar Explorer Map (nationalmap.gov).

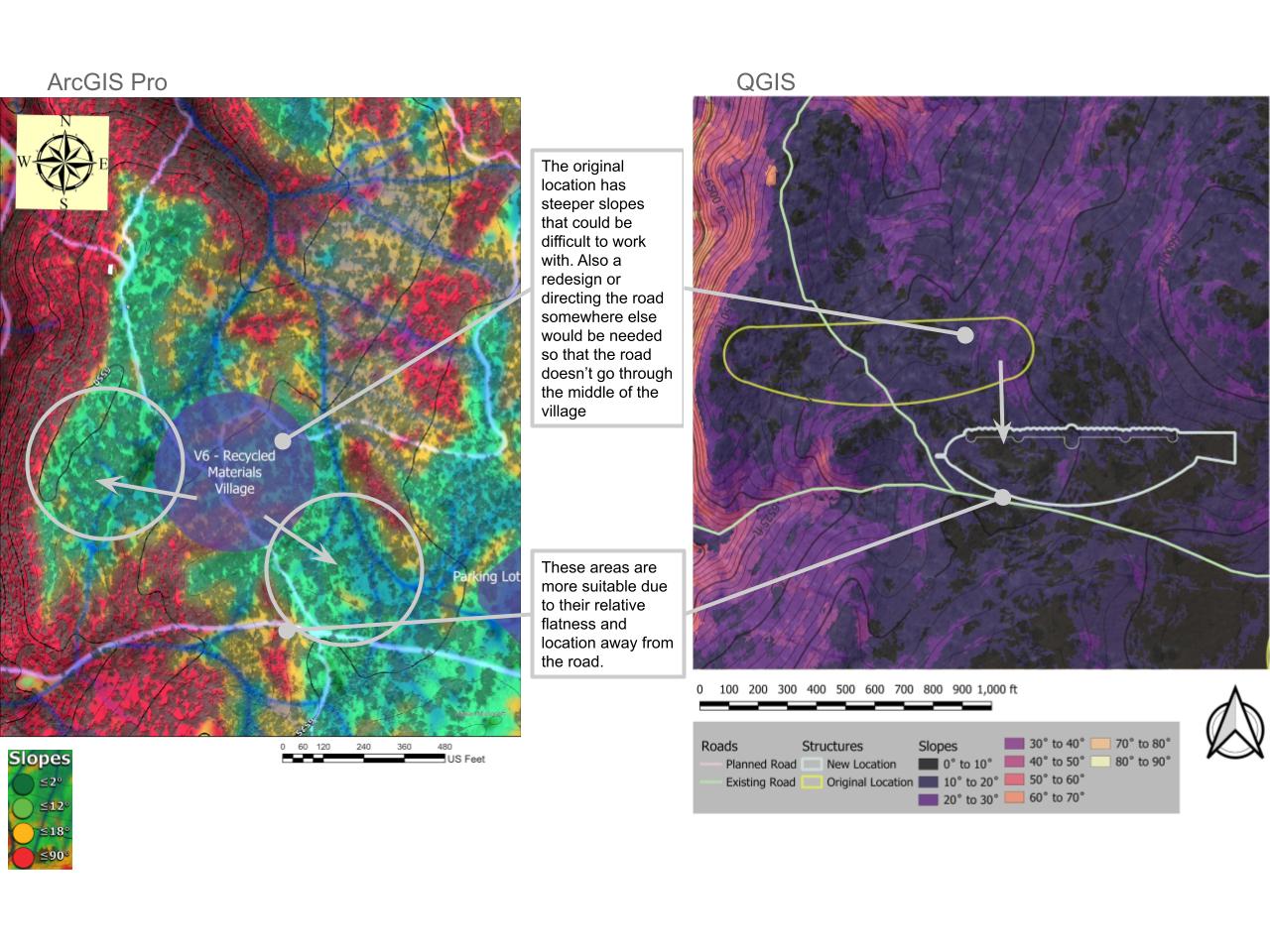

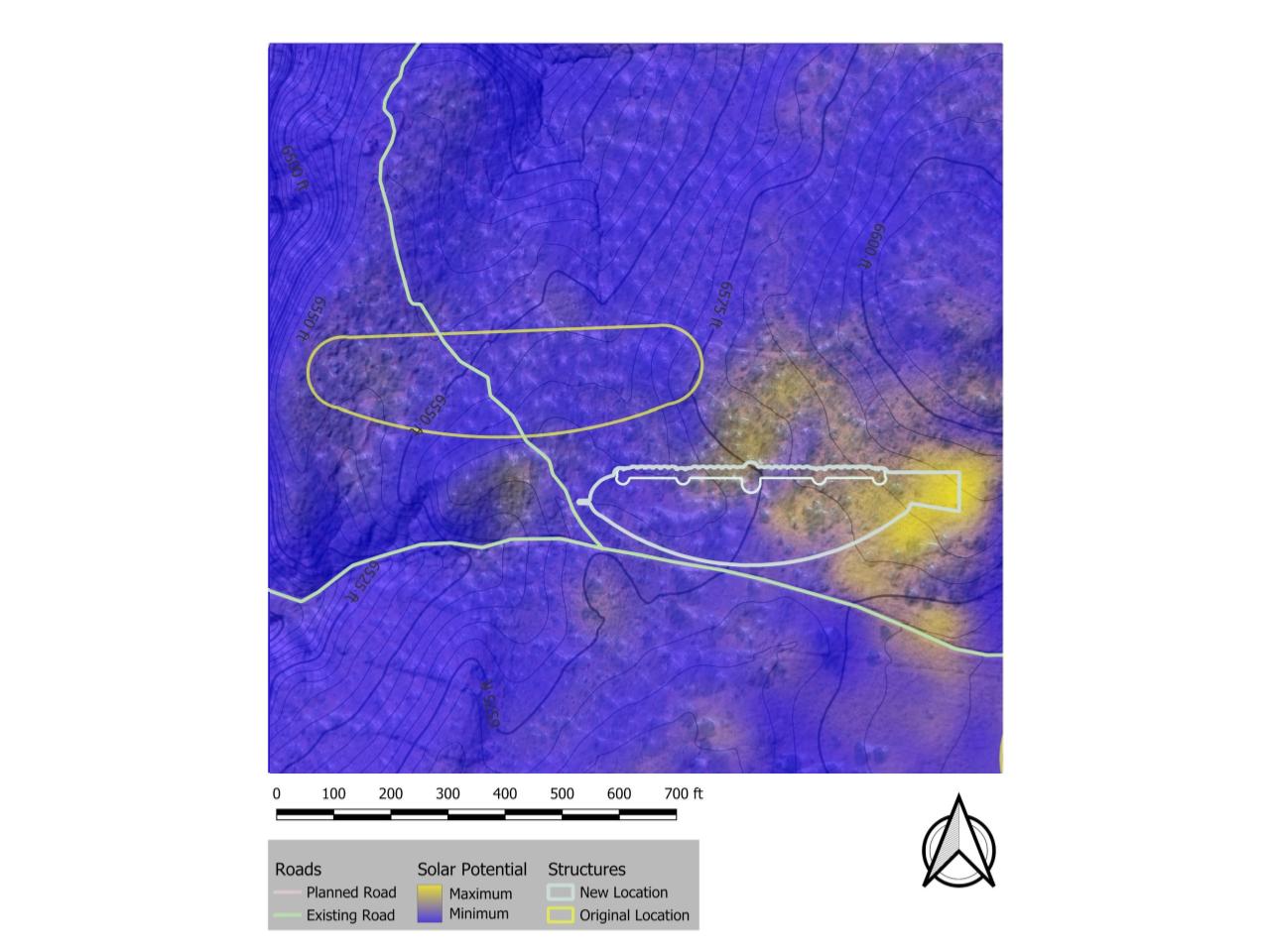

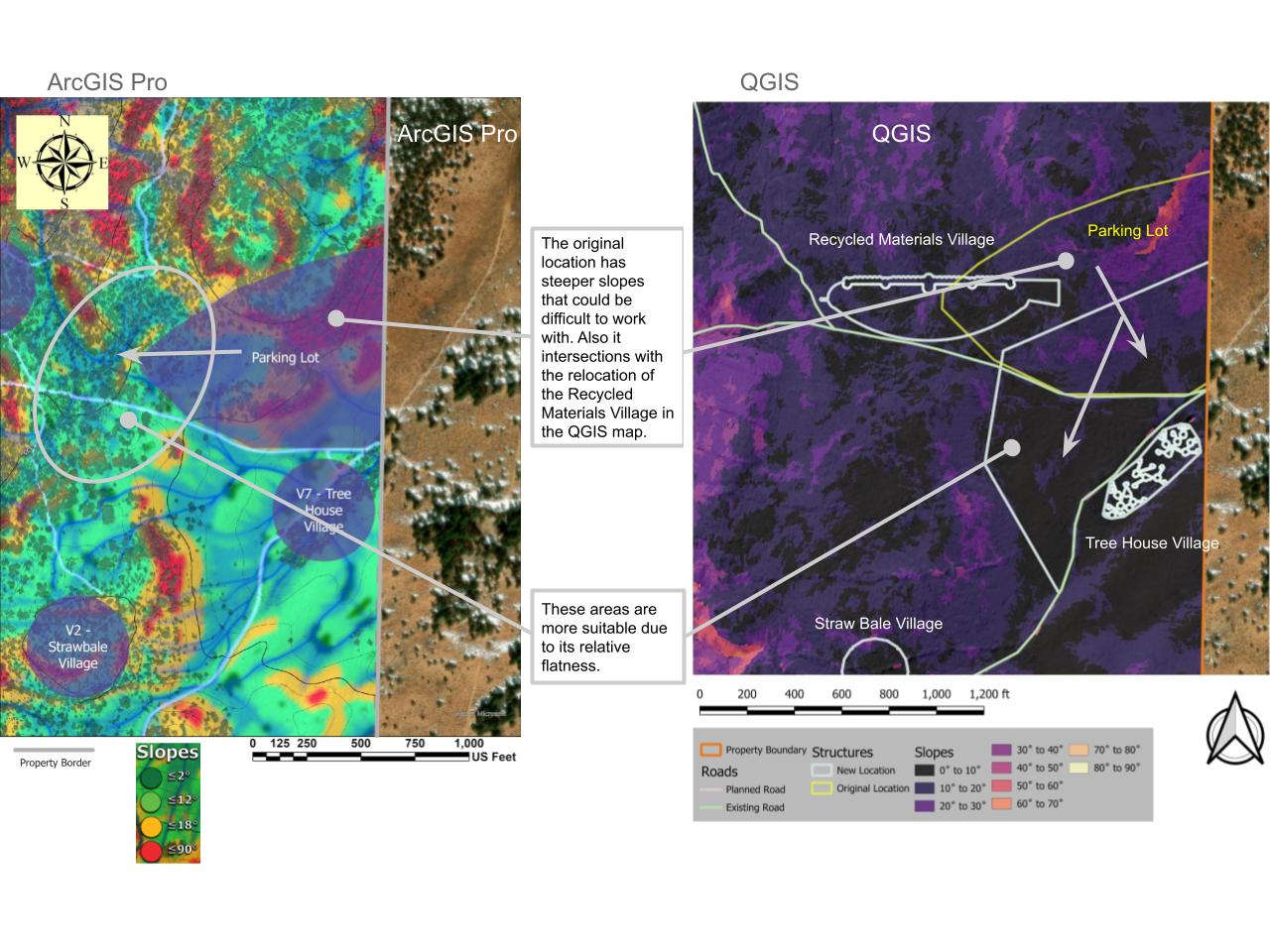

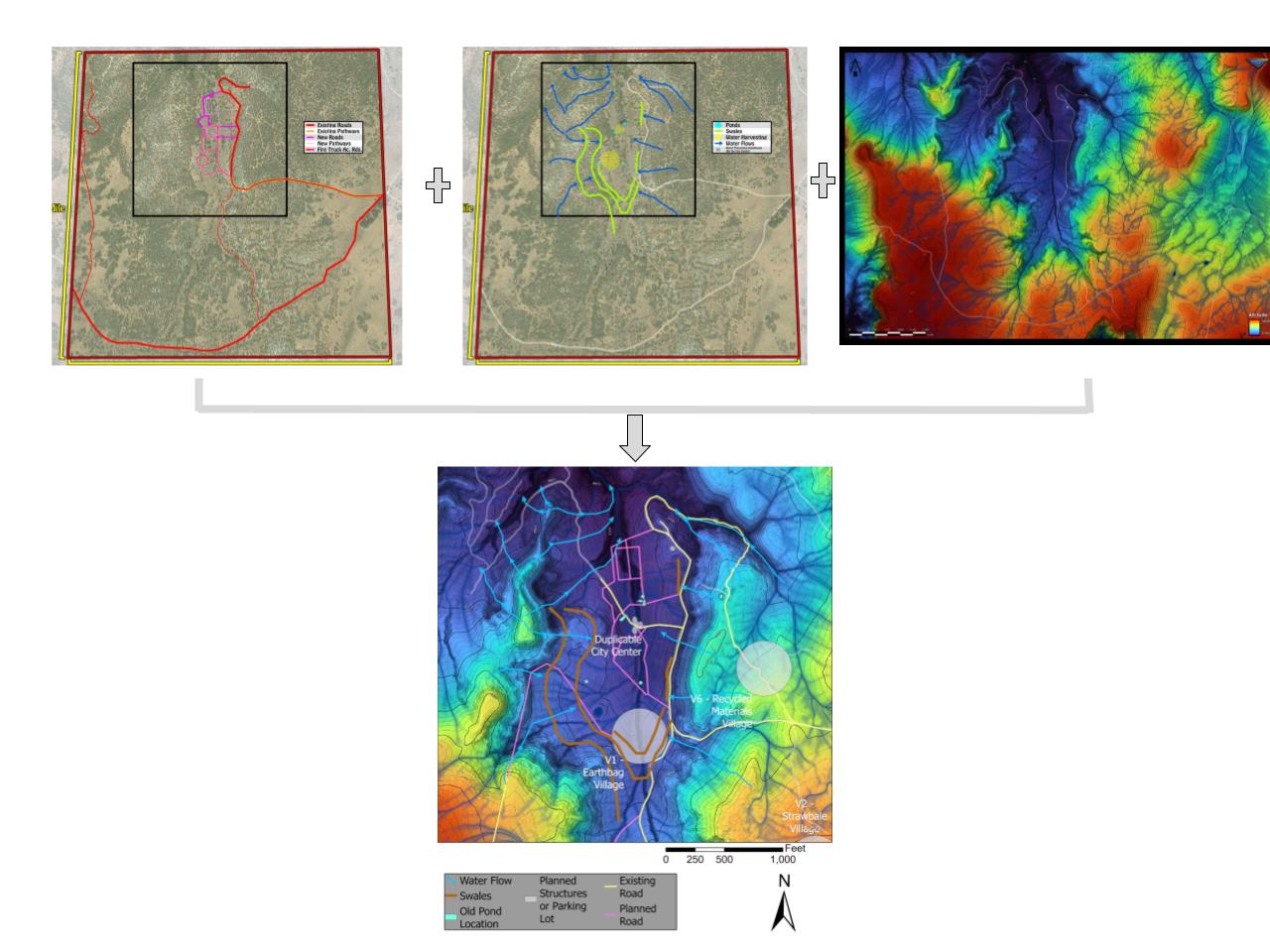

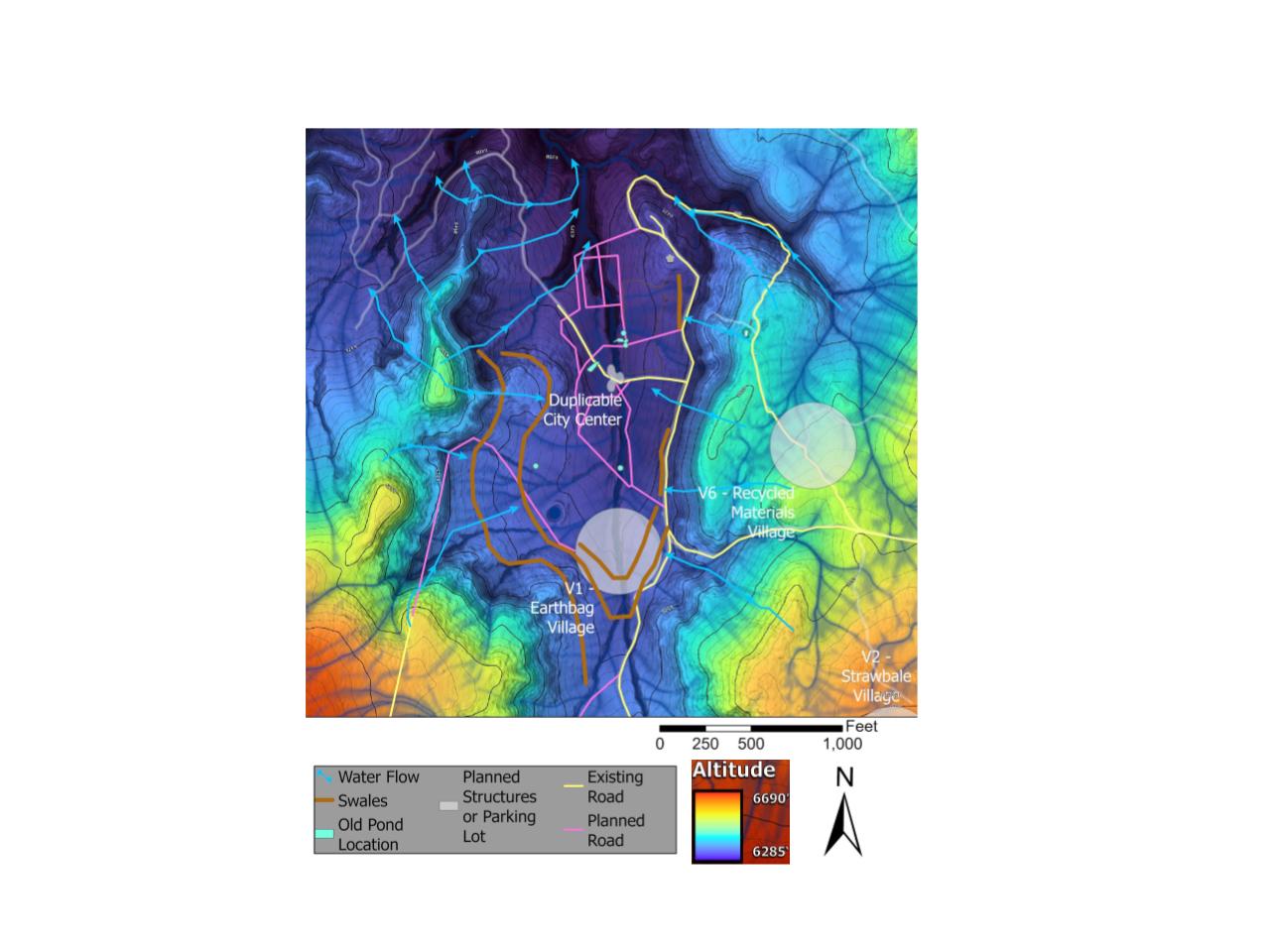

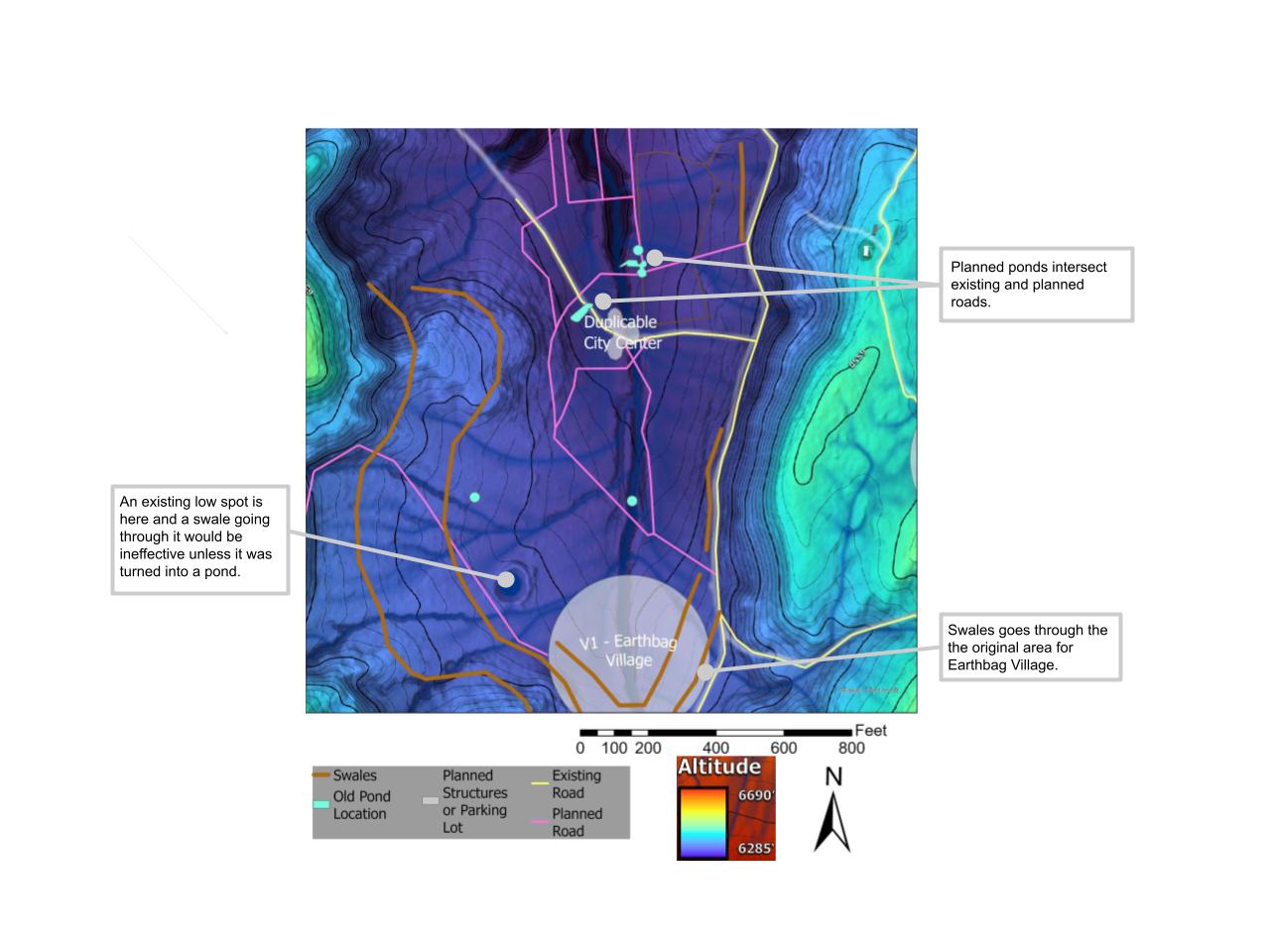

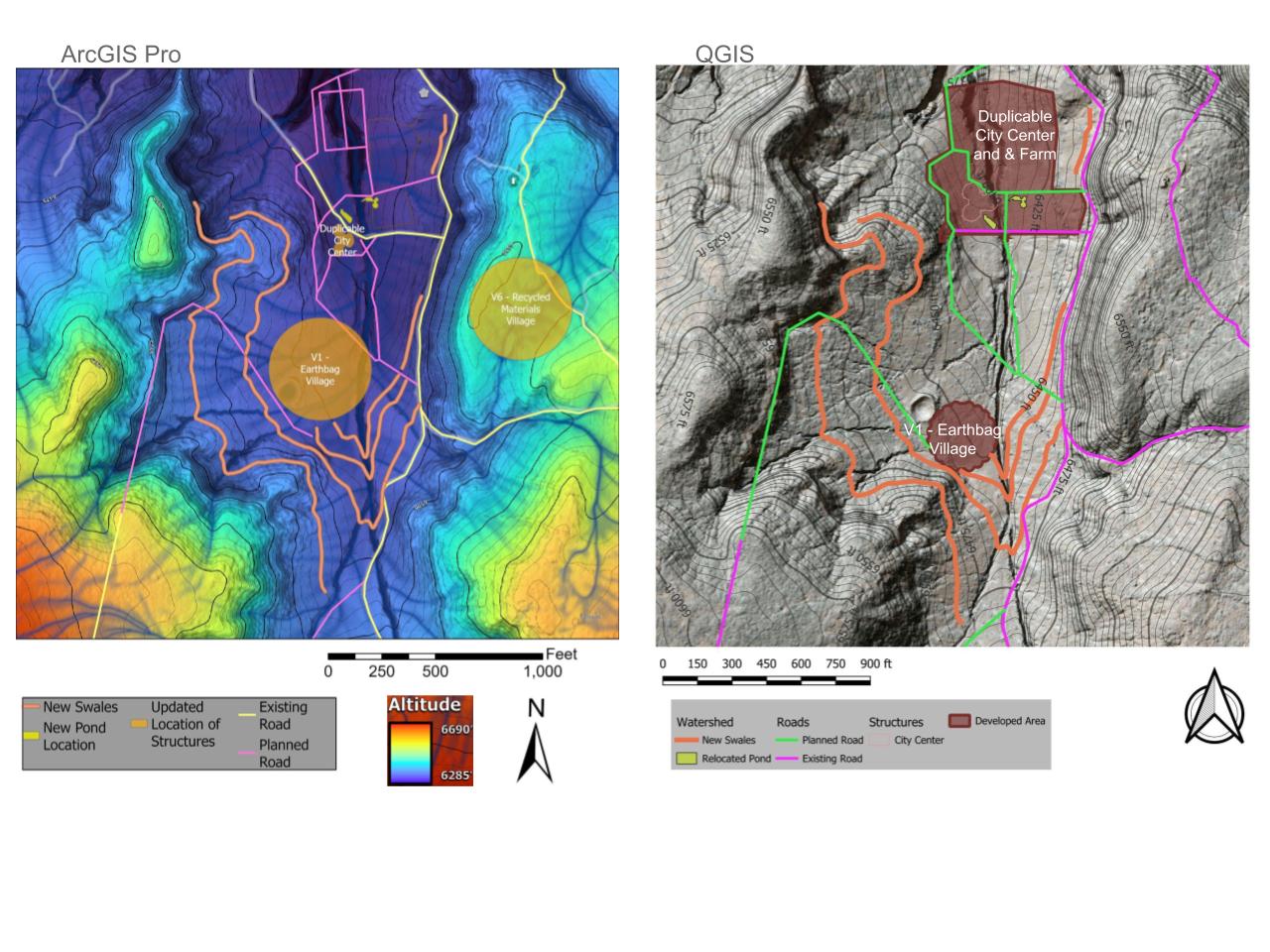

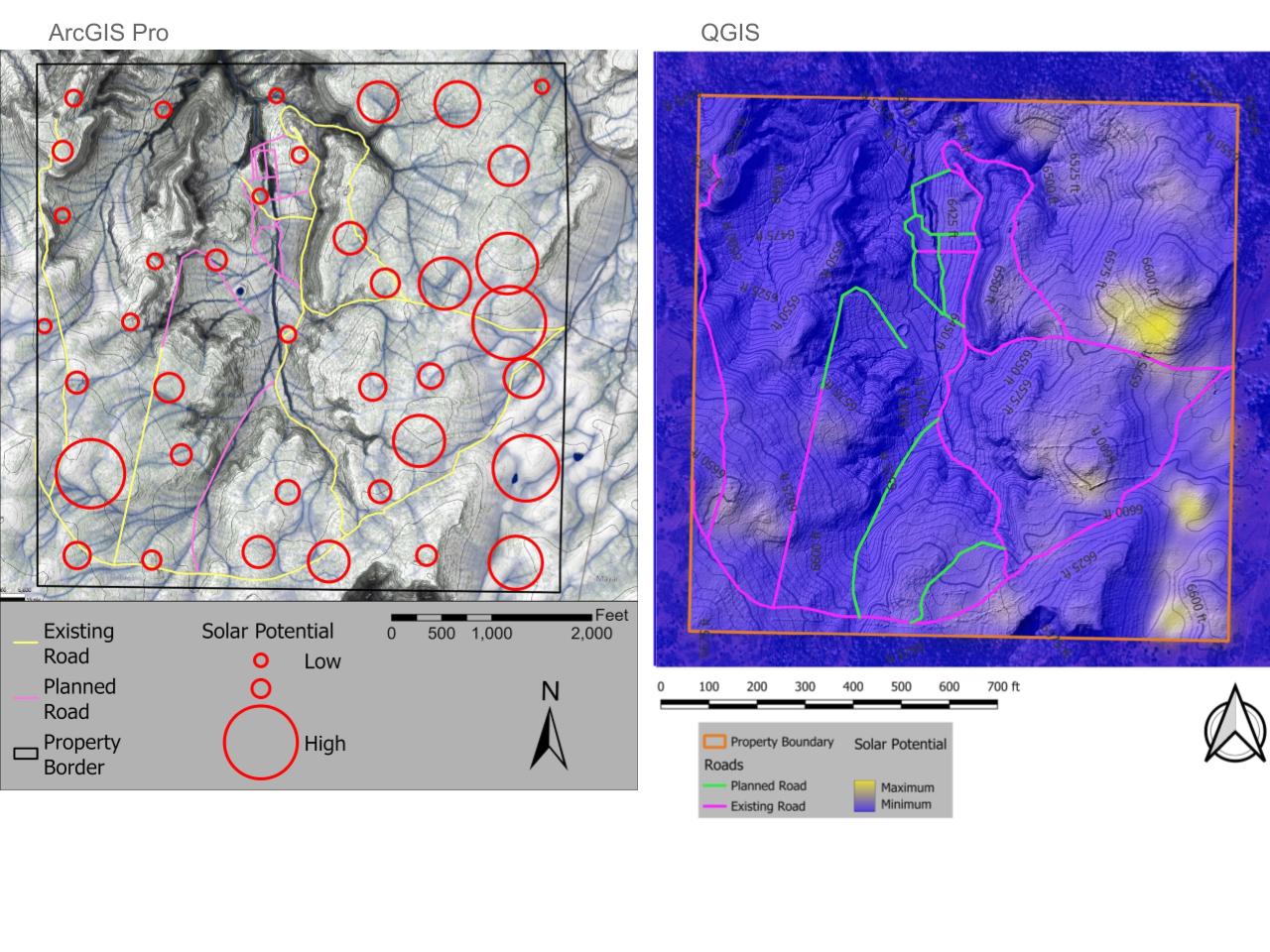

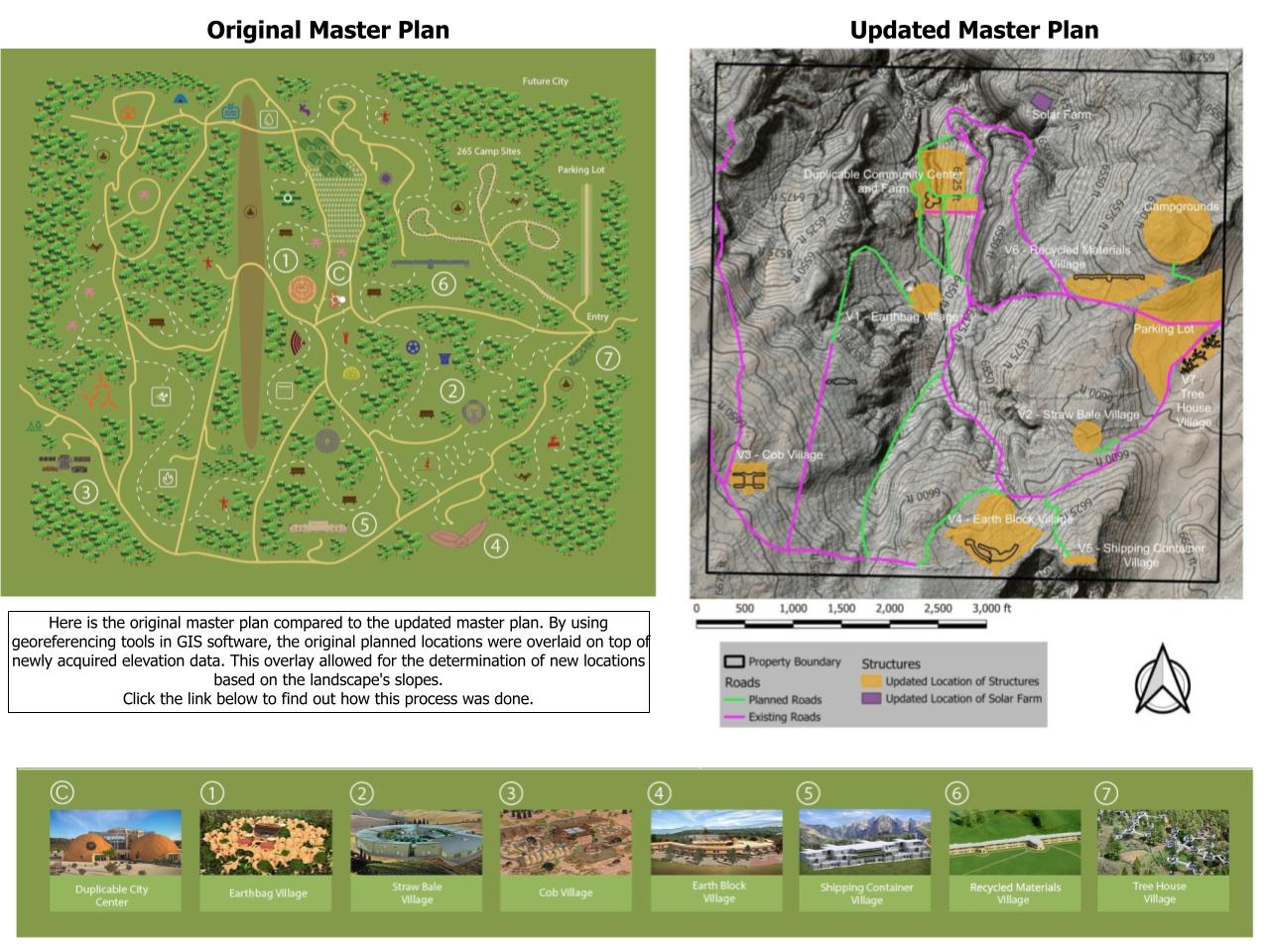

This level of detail showed mistakes and new opportunities in One Community’s masterplan layout of its structures and infrastructure that was based solely on contour maps. Further information on how GIS can be used in permaculture design can be found here: (link to the webpage with GIS content).

Ideally, spend one year observing before implementing your permaculture design. Become intimately familiar with the land that you are working with. Watch and experience the seasons. Walk the property as it rains so you can observe where and how the water flows and collects. During a rainfall is the perfect time to be outside to observe where the water is accumulating. Observe what plants thrive to learn about the soil conditions and microclimates. Walk the area taking notes, making drawings, and mapping. Note the topography, such as the high, low, and flat areas. Get to know the lay of your land in the context of the whole process. As you walk the property, mark up the basemap freely. Record any relevant information on the following topics:

- CLIMATIC FACTORS: Climate includes precipitation, temperature, wind, first/last frosts, and plant hardiness. Climate also includes other forces that move through the site, such as the sun’s rays, floods, fires, pollution, and wildlife.

- GEOGRAPHY: Landform or geography includes catchment area, topography, streams and other water features, it is the lay of the physical lands.

- ASPECT/ORIENTATION: The slope types, and landscape profiles (ridges, valleys).

- WATER: Water sources (creeks, dams, ponds) and flow directions.

- ACCESS: Driveways, footpaths, animal corridors, and farm areas.

- FLORA AND FAUNA: What’s thriving?

- INFRASTRUCTURE: Existing buildings, fences, and other man-made structures, such as water and sewage provisions.

- ENERGY COMPONENTS: technologies and sources (sun, hydro, wind, and/or bio-gas).

- SOCIAL COMPONENTS: People, culture, trade, economics, and legal.

RESEARCH AND ANALYZE OUTSIDE INFLUENCES

Research is key to closing the gap between that which was observable and that which is more efficiently collected using off-site resources, such as books, local experts, and the internet. This is the information age and there is a lot of valuable information out there that can feed into the design process. A helpful guide for this sort of research is provided by William Horvath’s How to Set Up a Permaculture Farm in 9 Steps and his Permaculture Farm Checklist.

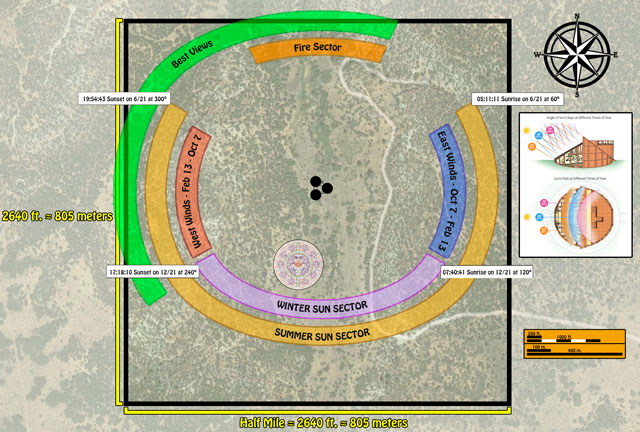

The major task during the research phase is to take inventory of outside forces that impact your goals and living situation. This is done through sector analysis and includes understanding the impact of the sun, wind, flooding, fire, pollution and wildlife. The sectors of a property are those elements that are set and difficult to change and/or have control over. Although there is little control over these elements, we can enhance or redirect them. Nature has both beneficial and detrimental forces. Depending on how a given force is interpreted and integrated, it can be the difference between success and failure.

The step to actually consider nature is foundational to permaculture thinking, which promotes working with and within the bounds of nature to create boundless, long-term yield. In working with nature, we protect our investments from detrimental natural forces and enhance our yield by tapping into the infinite energy source offered by nature, which secures the fate of our system and ultimately brings ease and harmony to our landscape and existence.

Collect as much data on the forces that exert the strongest unalterable influences to any action taken on the site. It is easiest to make multiple copies of the base map or, if working digitally, create digital layers. Start with about 12 layers and then label each page/layer as a “sector” to represent the possible factors influencing your site.

The most common sectors included are:

- CLIMATIC FACTORS: Sun, wind (this site is also helpful: wind), precipitation, and temperature variations, including first and last frosts, if applicable.

- GEOGRAPHY: landscape profiles and views worth preserving.

- WATER: Flooding/Draining, flows and directions, and watershed.

- FLORA AND FAUNA: Plant hardiness and Wildlife

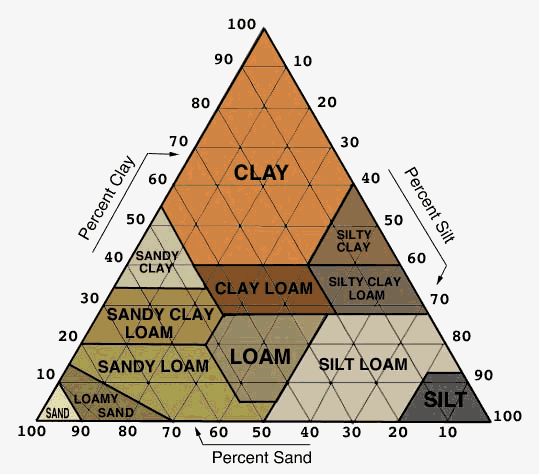

- Soil Types: Web Soil Survey

- UNWANTED INFLUENCES: Fire, Noise, Dust, Smells, Crime, Air/Water/Light Pollution

In addition to the resources provided above, a number of online resources are cataloged here that can help you understand your land and the surrounding area better. Here are a couple examples of what a sector map can look like – ours are included in the Case Study Section:

The sector analysis consolidates the effects imparted on the site that the dweller has little to no control over, without substantial input of resources, such as the sun, wind, water, fire, weather, and wildlife. We can either fight against these forces or work with them.

SUN SECTOR EXAMPLE

The most dominant outside force is the sun, so we have provided a more detailed discussion here. Whether to channel or shield the sunlight depends on the component of interest, so it is important to understand sun exposure. Understanding sun sectors becomes more relevant as you move away from the equator and have more dramatic sides of the property. One will be sun facing and hotter and dryer, and one will be pole facing, which will be shaded during winter months. The east side of the property is showered with morning light, thus warming earliest in the day, helping to burn away the frost. The west side receives the strongest sun at the hottest part of the day. Proper orientation in relation to the sun can provide maximum energy or protection, depending on the need of the particular component you are designing.

The sun’s exposure has 2 periods of extreme impact – during the summer and winter. Let’s explore how this works. The earth rotates around an axis and each rotation around that axis is considered a day. The earth’s axis is not perpendicular to the path the earth follows around the sun. Each rotation around the sun is considered a year. Here is a visual of the earth’s daily spin and yearly rotation and another explanation of the earth’s spin and rotation around the sun path can be found here:

During the earth’s rotation around the sun, the tilt of the earth does not change relative to the sun – for a period of a year, the north pole for all practical reasons points in the same direction. Right now, the north pole is pointing at Polaris (or the North Star).

From the perspective of the northern hemisphere, the two extremes occur when: (1) the north pole is facing away from the sun, which marks winter, and (2) when the north pole is facing the sun, which marks summer.

In the northern hemisphere, during the winter when the northern hemisphere has an apparent tilt away from the sun, two physical conditions contribute to the cooler weather – day length and intensity of the sun beam. The sun is hitting the northern hemisphere for fewer hours, as shown below:

And, the total amount of sunlight reaching the northern hemisphere is more dispersed because the sunlight is not hitting the surface of the earth head-on, but at an angle. So the light (or energy from the sun, including heat energy) is spread out over a greater surface area, as shown in the image below:

The sun path (or solar graph) diagrams show arcs and that is how much daylight a given area is getting. This video and this website explains the parallel between the sun chart and what is actually going on physically, along with the image below:

Two common terms used for a sun chart are azimuth, which is where the sun is relative to North and altitude, which is the vertical angle to the sun relative to horizontal, as depicted below:

The sun chart defines important parameters, such as the solar window, which lies between 9 AM and 3 PM and is also bracketed by the summer and winter trajectories – all from the perspective of looking towards the equator – the Earth’s rotational center. The following free sites are available to plot the sun’s path at any given location:

http://suncalc.net/#/45.997,-66.8751,11/2019.09.15/20:23

http://solardat.uoregon.edu/SunChartProgram.html

The University of Oregon site is simple and easy to use. The site outputs a chart like this:

Created for zip code 48317, near Detroit, MI.

A solar heat gain study was completed for One Community’s Tropical Atrium and the design was based on maximizing sun in the winter and minimizing sun in the summer. For this component, the angle of the sun and the apparent path of the sun during different times of the year were applied to capture the sun’s energy during cooler weather and deflect it during warmer weather, keeping the temperature inside the atrium optimal for humans and plants. Additional information is available here.

The following image shows how the windows were placed to harness this natural source of nearly infinite free energy during cooler months and the roof was placed to shield this powerful force during warmer months:

Solar Heat Gain in relation to Azimuth: Click to open the open source Tropical Atrium Temperature and Humidity Control in a new tab

SUMMARY OF CURRENT REALITY

The permaculture design process is a fun, yet long journey that requires a great ability to adapt within dynamic climatic and economic bounds. Organize the information gathered through observation and research and identify the strongest influences. This summarizes your current reality. Develop drawings and bulleted lists of what you have learned about the land to aid in the conceptual and more detailed permaculture design process, as well as answer the question: Are my goals achievable?

STEP 3 – DEVELOP A CONCEPTUAL DESIGN

The next step is to develop your conceptual design. Using all the information and analysis you’ve done to this point, now you can start to actually visualize and outline the specifics of what you want to create. This is just the concept design, the detailed design is step 4.

The observation and research phase resulted in a basemap, sector map, and other relevant information for the design of a system that optimally works with nature to minimize exploitation and human intervention. With this thorough assessment, the components of the property and zones can now be placed appropriately. With permaculture design, we make a deliberate effort to work with nature and its forces. The design journey can vary depending on which methods you choose to use. Several options are discussed in Bill Mollison’s Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual. A few are highlighted below, some of which have already been described and used:

- OBSERVATION: The site’s observable characteristics often reveal the design itself

- OPTION AND DECISIONS ANALYSIS: The design process is a series of decisions based on the options available and the characteristics of each component, and each choice informs the next decision that needs to be made.

- RANDOM ASSEMBLY: A method by which innovative combinations are formed by piecing together seemingly unmatched components. This often results in unexpected positive connections that do not naturally present themselves. This is discussed further below under STEP C.

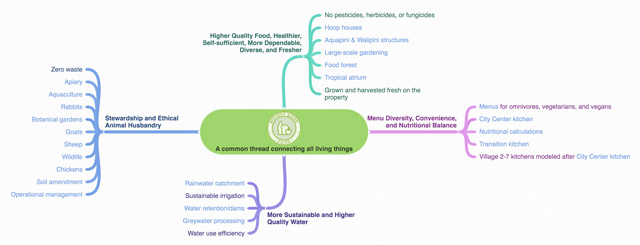

- FLOW DIAGRAMS OR MIND MAPS: Flow diagrams and mind maps are great ways to organize the design and/or see the connections and the flow of movement around the property. This is especially helpful when thinking about workflow and making daily tasks as easy as possible.

- ZONES: Placement of components based on zones is also a way to make life easier and increase flow. Zones are further described below under STEP B.

- SECTOR ANALYSIS: Placement of components based on the sector analysis makes life easier in the long run because we are following natural order and using it to our advantage rather than struggling for a lifetime to combat the inevitable. The map that resulted from the sector analysis is a layer that can now be used for the conceptual zone map.

- INCREMENTAL DESIGN: This is at the heart of the permaculture lifestyle. The design made on paper is merely the start of the journey. The journey itself is a gradual design process whereby continual adaptations contribute to a system that progresses towards improved efficiency and performance.

- DATA OVERLAY: This type of design uses map layers to best place components within a system, the layers can include topography, sun sectors, wind sector and the such.

Ultimately, no matter which process you go with, allow yourself to be guided by the permaculture principles. A permaculture system is ever-evolving and thriving on observations and trials and an openness to change (both expected and unexpected).

Here is a general 3-step process that combines a number of the above mentioned strategies and can be followed for the development of your conceptual design:

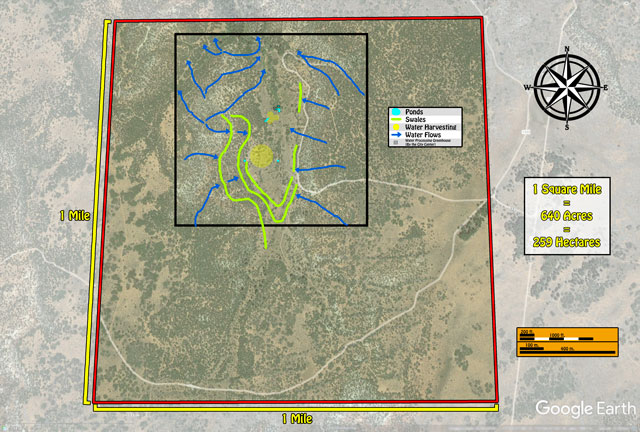

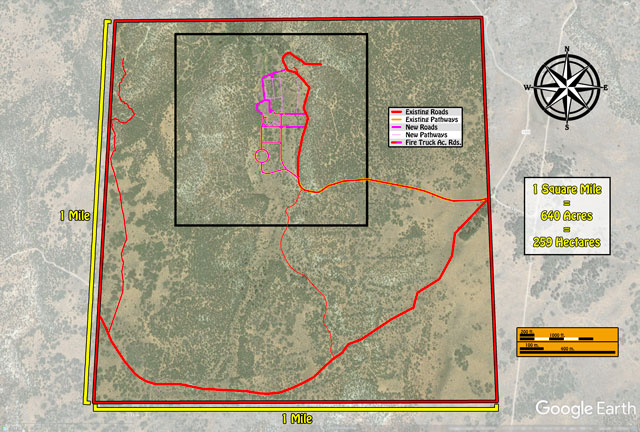

STEP A: MAINFRAME MAPPING

Begin with what Geoff Lawton calls the ‘mainframe.’ The mainframe components are the essential infrastructure, such as: water systems (water storage, harvesting, irrigation), access (farm roads, tracks, paths), and structures (house, outbuildings, portable structures).

During concept design the base map is marked up with the relative placement and rough size and shape of major features and functions. Rough bubble diagrams with notes can also accompany the map. Use your basemap and, in this order, place the following mainframe components:

- WATER: Darren Doherty calls climate “the rules of the game” and William Horvath calls the landform the “board on which you play.” Water is often considered on par with climate and landform, as this element is a prerequisite for life, growth, and surplus. There is substantial effort that goes towards harvesting and retaining water within the system. Water is optimally stored high in the landscape so the water is gravity fed when needed during dry periods. Topographic maps can be used to identify these logical locations. Tap into water sources for storage in this order, when possible: surface stream flows, ponds, rainwater, and underground aquifers. Swales on-contour, like those used with keyline cultivation, are particularly effective at slowly infiltrating the water to hydrate the landscape. The storage can be covered tanks or earthen dams. The first step to designing the water supply system is determining your water needs, which includes water for crops, livestock, and personal needs. One way to determine if your needs are met is to use the rule of thumb that 1 mm of rain on a 1m2 surface is equivalent to 1 L of water.

- ACCESS: The placement of roads and other access components is essential as this is what determines how you move through the property. When the property is easy to move around on, overall maintenance of the property becomes easier and adds to the overall enjoyment of the property. The best location for main roads are on ridges, because they stay dry and are easy to maintain. Other beneficial road locations include along boundaries and near channels. Roads can serve as much more than just access routes, if placed properly – roads are great water harvesting surfaces and fire breaks. Wherever they end up being, assure that the roads are on contour to prevent erosion and pooling of runoff.

- STRUCTURES: All structures should be designed and placed with water, sun, wind, and access in mind. When planning the layout of buildings and structures, it is important to first put effort towards looking after what you already have in place. The next priority is to restore what you can, and then lastly to introduce new components into the system. Buildings should be sheltered from the wind, not overly exposed to the sun, have good solar access, and should ideally be on a slope. Ancillary buildings, such as sheds, are ideally placed higher than residential buildings so they can house water tanks that are gravity-fed to the home.

The idea of working with natural forces is key to permaculture design. Our physical world affords a variety of free, unlimited natural resources, such as the wind and the sun. Working with the sun sector as it pertains to structures is given as an example here. In the northern hemisphere, the sun rises in the east and sets in the west while moving across the southern sky. How high and where the sun appears depends on the time of year and your geographical location. The closer you are to the equator, the higher the sun appears in the sky. Important angles to know for designing a building are the azimuth angle (horizontal angle along the horizon from due south) and altitude angle (vertical angle above the horizon). For example, during the summer in Detroit, MI, the sun does not set due west, but rather 58 degrees from due south. This information is advantageous when building or renovating structures. Because with this knowledge, we can maximize a site’s potential for passive heating and cooling. Good orientation reduces the need for heating and cooling. In the northern hemisphere, this typically means good southern exposure. Designing to let the sunshine in when needed (in winter) and keeping sunshine out in the summer, regulates the inside temperature naturally. Passive solar temperature control allows a house to heat and cool on its own. Passive solar is low tech and does not rely on mechanical devices, like HVAC systems that use fans, pumps, and electrical components. Controlling solar energy, both light and heat, reduces our reliance on fossil fuels.

There are a number of ways to utilize solar energy:

- DIRECT GAIN: Heating or cooling directly through solar gain or shadows, like what happens through a window with a sun shine or when an awning shades a window from the sun. The space is heated and lit when solar energy (radiation) passes through the window.

- INDIRECT GAIN: Heating or cooling indirectly through conduction of a thermal mass, like an outside wall that is heated and that heat is transferred into the home. The wall acts as a thermal mass that absorbs, stores, and distributes energy at a slow rate, which can help to regulate and control the temperature within a given space.

- ISOLATED INDIRECT GAIN: Heating or cooling an adjacent space then relying on convection to transfer the temperature, like a sunroom.

All passive solar designs use controls, such as insulation, overhangs, or vegetation, to control the way heat and light enters a space. This is happening by way of bouncing, filtering, and regulating solar energies.

Once water, access, and structures are positioned, the placement of other components becomes more apparent.

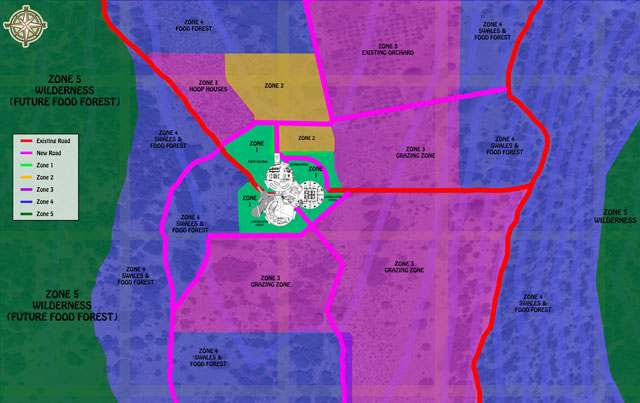

STEP B: ZONES

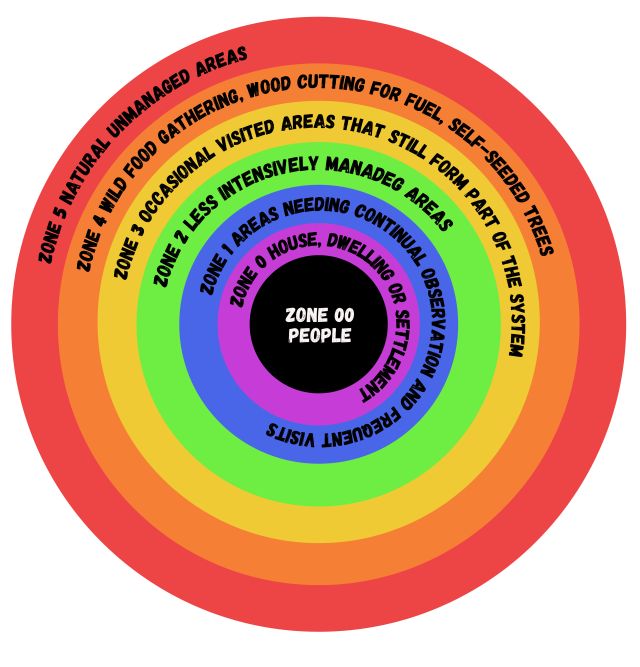

Zones are an interesting concept that implements a common phenomenon, namely that humans maintain what is closest in proximity. Zones are a guide for the placement of components based on how much human input is necessary. Here is a simplified zone map, although shown as concentric circles here, in actuality the zones end up being different shapes (greatly based on the sector maps) and sometimes with disconnected areas:

The final product of the concept design needs to include a map that delineates your zones and sectors. The delineation of zones organizes the space based on how often it needs to be accessed or needs attention. Sectors delineate and define how outside forces impact our site. Zones and sectors allow us to create a design that meets our needs, as well as works with the sways of nature. In order to do this you have to have a central point, and this point is your dwelling. If your dwelling does not exist yet, you may try multiple locations and create multiple maps with zones and sectors for the different dwelling location options. So this point is a great time to identify and work with all your zones.

The final product of the concept design needs to include a map that delineates your zones and sectors. The delineation of zones organizes the space based on how often it needs to be accessed or needs attention. Sectors delineate and define how outside forces impact our site. Zones and sectors allow us to create a design that meets our needs, as well as works with the sways of nature. In order to do this you have to have a central point, and this point is your dwelling. If your dwelling does not exist yet, you may try multiple locations and create multiple maps with zones and sectors for the different dwelling location options. So this point is a great time to identify and work with all your zones.

Your zone map should be a layer on the map that provides some guidance as to the placement of components, reminding you to keep the work-intensive components near your dwelling. The easier it is to access the things that need the most attention, the greater chance that they will be properly maintained. So the most energy intensive components are placed near the dwelling, which is the central point and diminishing energy needs radiate out, with the most unmanaged areas on the outskirts of the property and furthest from the dwelling.

Here are some details on each zone in bulleted form, as well as a summary table:

- ZONE 0: Zone 0 is where the design starts. This is our home, where we spend the majority of our time. The home is ideally built with local resources and designed in a way that the sun and wind serve as natural climate controls, so outside energy input is unnecessary to maintain comfortable indoor temperatures. Also, the home is designed to catch and store water to meet household needs. The waste cycle is a closed loop, generating only the waste that the property can handle. Zone 0 is the smallest sector, typically made up of a relaxing and welcoming home.

- ZONE 1: Zone 1 is the high-traffic zone surrounding the home. After the home, this area is the most accessed with the most human input imparted – requiring daily attention. This area supplies the majority of our needs – this is where kitchen crops are grown and quiet animals are reared, such as fish, rabbits and compost worms. The success of this zone is guided by humans. This zone is designed for diversity (25+ planned species) and dense productivity (high produce growth per square foot). For a small family, Zone 1 is typically ¼ to ½ acre in size.

- ZONE 2: Zone 2 surrounds Zone 1 and is the nexus between human intervention and allowing natural processes to flourish without exploitation – requiring seasonal attention. This zone is for components like your crops that can be stored easily and eaten throughout the year, noisier animals such as poultry, milking cows, and goats, as well as trees for firewood harvesting, windbreaks, and visual barriers. This would be your first place to plant a food forest also, which could also be extended into other zones. Like Zone 1, this zone is also designed for diverse species (25+ planned species). The size is typically 1 to 2 acres.

- ZONE 3: Zone 3 is the grazing zone and increasingly guided by nature, with little human intervention – often requiring only yearly attention/intervention. The components are much larger, comprised of pastures, large windbreaks, woodlots, hardy fruit trees and additional food forests. This zone is designed for a limited number of market species (10 or less) and is substantially larger, 3 to 10 acres.

- ZONE 4: Zone 4 is a wild forest that supports fungi, bamboo, and timber. This zone is also designed for a limited number of market species (10 or less) and requires little attention – occasional pruning and harvesting on a decade timeline. This zone is on the order of 100 acres.

- ZONE 5: Zone 5 is wilderness that is maintenance-free and serves as a recreational and educational area to learn from nature and the ways in which nature is utilizing the climate and the setting in which we are living.

STEP C: COMPONENTS

List the components that already exist and the components that you wish to have within your property. Include everything on the property – all buildings, all animals, roads, energy, water, skills, and other land uses. A small farm will have these components: a house, barn, greenhouse and chicken coop. Other components could include cows, sheep, goats, rabbits, gardens, pastures, food forests, wood for fuel, roads, water systems, as well as conceptual components such as labor, finance, skills and market.

Here is an extensive list of common components developed by Geoff Lawton (your site may have additional components based your unique needs and your property’s unique potential):

- Water

- Irrigation water

- Drinking water

- Access

- Roads, footpaths, etc

- Crossing pipes over water systems (swales and spillways)

- Structures

- Houses

- Plant houses

- Ponds

- Fences

- Boundary

- Animals

- Crop Gardens

- Kitchen gardens

- Main crops

- Plants / Trees

- Planting guilds

- Species: Perennial, Annual

- Waste Systems

- Waste water

- Recycling

- Utilities

- Grease traps

- Composting

- Worm farms

- Reed beds

- Aquatic Systems

- Plants

- Animals

- Fungi Systems

- Tools and Machinery

- Energy Components

- Animal Systems

- Small animals

- Large animals

ANY OTHER DESIGN COMPONENTS:

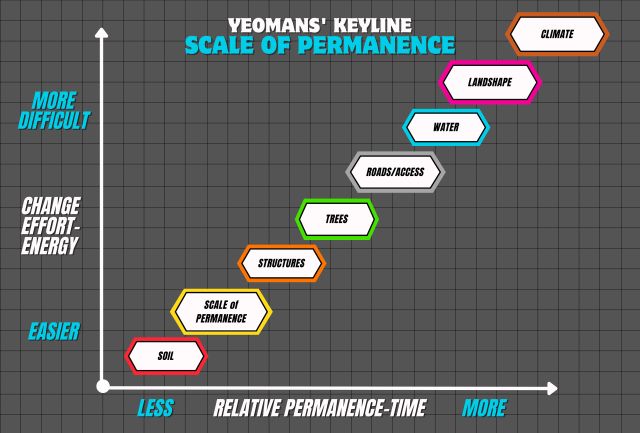

Another approach for developing the list of components is using the Scale of Permanence, originally coined by P.A. Yeomans, an agricultural designer. In the original list by Yeomans, there are 8 factors needing consideration, which are listed in the order of their permanence – a combination of how much effort it takes to change it and how long it functions without changing.

Since its introduction, the list has been adapted and altered, but Yeomans list remains relevant and includes the following, in order of greatest permanence to least permanent.

- Climate

- Landshape

- Water

- Roads/Access

- Trees

- Structures

- Subdivision/Fences

- Soil

This graphic is a helpful learning tool:

We think the Scale of Permanence is helpful because it guides you to work with the most permanent (fixed, unchangeable, or requires significant energy input to change) components of your land first, so the more flexible components are best fit within that context and within the constraints and latitudes. This is on par with the principle of Design From Patterns to Details. In its simplest terms the Scale of Permanence and the principle Design From Patterns to Details are proclaiming the importance of working with and learning from nature, because nature has the final say for the long-term survival of any endeavor.

A revamped list was developed by permaculturists Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier that incorporates both the ideas of the Yeoman’s keyline design, as well as permaculture design:

- Climate

- Landform

- Water

- Social and Economic factors

- Access and Circulation

- Vegetation and Wildlife

- Microclimate

- Buildings and Infrastructure

- Zone of Use

- Soil

- Aesthetics and Experience

The following table by Tara Hammonds summarized each of these components:

Once you have all your components listed, start thinking about how they are all connected and/or could be connected. Think about the energy inputs and outputs of each one and how the energy transfers between them.

Energy is transformed or transferred from one system to another and this transfer/transformation process is not 100% efficient. This causes an increase in entropy or messiness. At the top of a mountain there is highly dense energy, but little life, whereas in the lowlands, especially around estuaries, there is high life energy and low potential energy. The goal of permaculture is to extend and spread the life of a system, which means slowing down and spreading out entropic loss to gain a life advantage – transferring trapped energy from one component to the next as many times as possible before the energy is transformed into a form that no longer serves the system as a whole.

Overall, we are aiming for growth and yield from a system that starts out needing substantial maintenance and then gradually transforms to a system that just needs to be managed. To achieve this objective, it is important to use nature as your directive and the core resources offered by nature – sun, wind, rain, air, beauty, and the landscape itself. An annual garden takes a lot of energy input, but the remainder of the permaculture design is nearly self-managed based on implementing lessons from nature and maximizing the energy stored in the system.

When designing, think about how you can link the different components within your complex living system. Integrate chickens for pest management and organic fertilizer, more than just meat and egg production. Collaborating with cows for regenerative soil building through rotational grazing, generating milk and beef production as a byproduct. Mimicking the natural processes within nature in conjunction with animals will create a cooperation to reconstruct our ecosystems, rebuild the soil, and regenerate our land. Aim for diverse productivity that is self-regulating and not exploitative. Interconnectedness brings stability by making it so the breakdown of one component doesn’t mean a complete failure because there is backup and support. Connected systems built on diversity generate abundance, collective benefits, creative co-creation that develops nurturing and regenerative cultures. Separated systems create outputs of depletion, competition, scarcity, culture-nature spilt, and homogenization. This encourages exploitative and degenerative cultures. Interconnected permaculture systems reside on the nexus of order and chaos – we promote wild forests that do not require our input to thrive while also maintaining organized vegetable gardens that require our input to even exist. The true goal is to strike a balance on the land that results in a self-replicating and self-regulating system with minimal human intervention and labor.

During this process, consider the needs and inputs of each component and consider assembling components so they serve each other. The more you do this the more you will see components supplying the needs and utilizing the outputs of each other. Establishing strong connections between components minimizes our work and leads to a more stable and supported system. Take the time to describe the attributes you seek for each component and how they can support each other. Make sure each component in the design is getting its needs provided by other components that are also part of the overall design, so each component serves and nurtures other components within the overall design.

RANDOM ASSEMBLY

Once you’ve considered zones, permanence, and made your lists and drawn as many connections as you think you can, Random Assembly can be a fun way to guide you to think outside the box and consider links and interactions between unseemingly paired design components. Begin by rewriting all the components that need to be placed on your land on individual cards. Examples would be vegetable garden, ducks, ponds, access path, shed, drain pipe, dam, and greenhouse. Write each one of these on a note card and place them face down.

Now write six linking words on a different colored note card. Use prepositions like these:

- Above

- Under

- On

- In

- Between

- Beside

- Far from

- Attached to

Next, pick two components at random and one linking word to place between them and see what comes up. At right is a photo of how it can look.

Have fun with the process. Give each combination a chance and take note of each combination and whether it is positive, negative or interesting. Explore what you have learned through this process by asking yourself these questions:

- Would any of these new ideas work?

- Should these ideas be incorporated during the Detailed Design step?

- Did any of these connections teach me something I might want to avoid?

- Did I come up with any new components that I may have forgotten?

- Save what you learned here for the next step, Developing A Detailed Design.

SUMMARY

As the conceptual design comes to fruition, we want to assure that we have accumulated all the relevant information that is available at this stage of the process. These can include things like having a general understanding of the property and how our choices may impact the other aspects of how the property functions, as well as the property’s potential. At this point, it is also important to be aware of any limitations and challenges present, this should include things such as fire, frost, pests, etc. Along with these challenges, come resources and unique beneficial aspects of the property in the form of plants, skills, and landscape. This thorough scouring, scrutiny, and assessment of the information available, leads to a design that is a robust starting place for small trials and performance-based feedback that ultimately leads to a sustainable overall system.

STEP 4 – DEVELOP A DETAILED DESIGN

Developing a detailed design is the final step. This is where you design the details of what you’ll actually do. This last step is done on paper and is the culmination of the entire process described up to here. This step can be a real rabbit hole because each component could have a whole website about it. As you put this section together, use all the resources you have available to you (people, books, online, etc.) to understand the intricacies of each component you are planning to include.

The primary book used by most during the actual details of the design of each component is Bill Mollison’s Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. Other books recommended online include: Regrarians Handbook by Darren J. Doherty, The Bio-Integrated Farm by Shawn Jadrnicek, and A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander. There are also many excellent online resources. Take the time you need to find the resources that are best suited for your situation and your learning style. Be quick to post on forums and reach out to the community that has practical applied experience. These are the resources that we found especially helpful during the development of this tutorial:

- Permaculture Apprentice Resource Page

- Setting up a Permaculture Farm Checklist PDF

- A Resource Book for Permaculture – Solutions for Sustainable Lifestyles PDF

- How to Set Up a Permaculture Farm in 9 Steps

- The Ultimate Guide to Starting a Profitable Permaculture Farm

Along with the above mentioned resources, here is a list of potentially valuable or interesting links (from a quick internet search) for designing the details of each component:

- Water

- Access

- Structures

- Living Fences

- Crop Gardens

- Perennial

- Fruit Tree Guild

- Planting Guilds

- Food Forest

- Nursery

- Soil

- Monetary Profits

- Animals/Animals

- Chickens

- Aquatic systems

- Fungi Systems

- Tools and Machinery

- Waste systems

- Waste water

- Energy

For each component, complete the following chart to summarize the thinking behind it (Swales and Chicken have been completed as examples):

Now that you’ve got all the information you need, create your detailed design. The detailed design is a collection of drawings and images that provide sufficient details for the actual implementation of your ideas. Start by placing tracing paper over the base map and experiment with the placement of the things you want. Draw at least 4 different potential designs that detail actual size, shape, and placement of each component, all the while maximizing the positive connections between components. Allow your mind to wander, be creative, and work without bounds. Keep the permaculture ethics and principles in the forefront and allow them to guide you and check back frequently with the results from the random assembly exercise and your research.

Out of the potential designs you develop, pick out the one that is most practical, efficient, and low-maintenance and you are ready for Step 5 – Implementation and Evaluation.

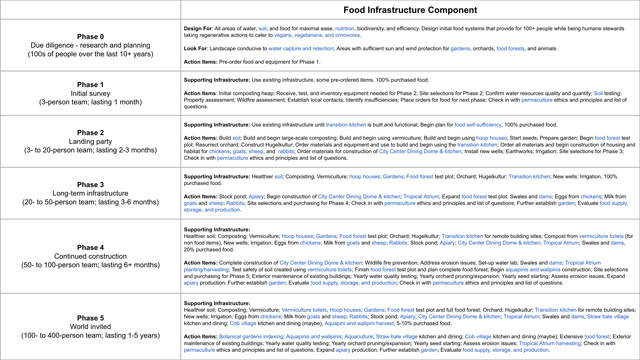

STEP 5 – IMPLEMENTATION & EVALUATION

The implementation phase is when the design is installed. The pace at which this happens depends on your unique situation and personal, environmental, technical, seasonal, and financial factors. This stage has a smoother rollout if you make a plan of action you can follow. The plan details the logical order of execution – basically a ‘to do’ list with a basic timeline that covers the first three years. The logical order for implementation is to (1) look after what you have; (2) restore what you can; and lastly (3) introduce new elements.

An overall approach can look like this:

- Fencing: An effective way to subdivide the property is to follow the transitions made by the more permanent infrastructure. The main fenceline often ends up closely following roads, enclosing animals, and planting areas. The zones can also guide the placement of fences. Flexible and mobile fences can be especially beneficial for areas enclosing animals as part of the regenerative process.

- Soil is low on the permanence list, because depleted or unhealthy soil can recover quickly – 2 healthy inches of soil can be converted every year. Soil is however the backbone of the system and warrants immediate attention to building the soil. This will contribute to securing a successful first round of planting. Soil is an excellent indicator of success. Several simple methods can be selected to improve soil fertility, such as keyline ploughing, cover cropping, mulching, erosion control, biofertilizer and compost tea amendments. Giving the soil life is the best thing you can do to propagate life. Be creative and allow yourself to learn from nature. Continue to amend the soil and allow the richness to penetrate deep into the soil. A great guide to building deep rich soil is available here.