Open Source DIY Earth Dam Design & Construction for Water Retention, Pond & Lake Creation, etc.

This page is about earth dam construction for water retention purposes. Building a small to medium-scale earth dam like the ones described on this page can provide water for irrigation, aquaclture, recreation, ecosystem restoration, and other uses.

Note: We are not experts in earth dam design. We’ve just done an immense amount of research on the topic after identifying a need for earth dams as part of the open source One Community Highest Good Housing and Food components.

We share all we’ve learned with the following sections:

- What is Earth Dam Construction

- Why Open Source Earth Dam Construction

- Ways to Contribute to this Open Source Component

- DIY Earth Dam Construction Steps

- DIY Earth Dam Disaster Risk Mitigation

- Dam Risk Analysis, Assessment and Management

- Risk Communication and Emergency Preparidness

- Resources

- Summary

- Frequently asked questions

RELATED PAGES (Click icons for complete pages)

CLICK THESE ICONS TO JOIN US THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA

WAYS TO CONTRIBUTE TO EVOLVING THIS SUSTAINABILITY COMPONENT WITH US

SUGGESTIONS | CONSULTING | MEMBERSHIP | OTHER OPTIONS

KEY CONSULTANTS TO THIS COMPONENT

Julia Meaney: Web and Content Reviewer and Editor

Loza Ayehutsega: Civil Engineer/Assistant Civil Engineer

Yi-Ju Lien: Environmental Engineer

WHAT IS EARTH DAM CONSTRUCTION

Earth dam construction is a viable option in many places for water storage and pond or lake creation. Systems will vary from place to place, so the design of your water storage feature warrants flexibility and careful observation of the surrounding landscape. The ideal solution is one that maximizes water storage and minimizes human intervention. This can be accomplished by mindfully educating ourselves on the natural elements we are working with.

Earth dam construction is a viable option in many places for water storage and pond or lake creation. Systems will vary from place to place, so the design of your water storage feature warrants flexibility and careful observation of the surrounding landscape. The ideal solution is one that maximizes water storage and minimizes human intervention. This can be accomplished by mindfully educating ourselves on the natural elements we are working with.

The earth dam construction content here is from hours of research on this topic. Our goal is to organize what we’ve learned into some broad guidelines and hopefully turn a nebulous and daunting task into a viable water-retention solution. The overall steps of the process are outlined in the flowchart below.

WHY OPEN SOURCE DAM CONSTRUCTION

Dams encircle the lower perimeter of where water wants to flow to create ponds that are replenished by both surface runoff and subsurface flow. Although water tanks are preferred for drinking water, they can cost 100x more for the same amount of water stored in an earth dam. The ponds and lakes created by small earth dams also develop valuable wetland ecosystems, beautiful recreation areas, aquaculture options, and large-scale water storage for emergency and/or agricultural use. Small DIY earth dams minimize flooding during the wet season, keep water from drying up during the dry season, combat erosion, and allow the standing water behind the earth dam to better percolate into the ground, recharging the groundwater and raising the water table. In addition, small DIY earth dams also lend the possibility of serving as small scale electricity generation for supplemental power needs through properly planned mini and micro-scale hydro power options.

Dams encircle the lower perimeter of where water wants to flow to create ponds that are replenished by both surface runoff and subsurface flow. Although water tanks are preferred for drinking water, they can cost 100x more for the same amount of water stored in an earth dam. The ponds and lakes created by small earth dams also develop valuable wetland ecosystems, beautiful recreation areas, aquaculture options, and large-scale water storage for emergency and/or agricultural use. Small DIY earth dams minimize flooding during the wet season, keep water from drying up during the dry season, combat erosion, and allow the standing water behind the earth dam to better percolate into the ground, recharging the groundwater and raising the water table. In addition, small DIY earth dams also lend the possibility of serving as small scale electricity generation for supplemental power needs through properly planned mini and micro-scale hydro power options.

Tamera Eco-Settlement Water Conservation Results: This Took Less Than 4 years

EARTH DAM CONSTRUCTION DETAILS

Our goal with this page is to share everything our research has taught us about DIY earth dam construction. There are many different types of earth dams that you can construct, but the basics of construction are the same. The image below shows the most common earth dams and we use the following sections to discuss each of these (and others) and the ways to build them:

- DIY Earth Dam Legal Considerations

- DIY Earth Dam Safety Considerations

- Sealing a Pond or Lake

- Types Of Earth Dams

- Earth Dam Construction Details

- DIY Earth Dam Construction Case Studies

- DIY Earth Dam Cost Analysis

- DIY Earth Dam Disaster Risk Mitigation

- Resources

- Summary

- FAQ

DIY EARTH DAM LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

You must be aware of and adhere to local laws before constructing an earth dam. Failure to do this can lead to forced removal of your construction. Plan ahead for this because meeting with the local watermaster, local county authority for land use permitting, fish and wildlife services, and/or the state for permission can take 6 months or more

DIY EARTH DAM SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

Depending on the size and location of your earth dam, you may also need to enroll a civil and/or structural engineer in the design process. Here are a few of the things to think about:

- Consider your materials for construction. Do you need an engineer to identify if they are sufficient for your purposes?

- Consider what would happen if your earth dam were to suddenly burst and release all its stored water at once. What is downstream from that? Do you need an engineer to make sure this will not happen?

- Consider the permeability and slope of your land. Could the water you are storing cause a landslide? Do you need an engineer to make sure this will not happen?

- Consider animal/ecosystem impacts from your pond and on your pond

- Consider your seismic zone

These and any other safety concerns need to be thought of and addressed from the beginning.

Constructing an earth dam without proper safety measures can result in structural failures, landslides, or ecological damage. Engaging engineers and addressing site-specific risks ensures the dam’s stability and the safety of surrounding areas, preventing catastrophic failures.

It’s a scary business, it’s scary designing, especially when a lot of dirt’s been moved and sheets of water are spreading across the landscape. That’s scary. And if it scares you too much, get someone in to do it.

~ Bill Mollison ~

SEALING A POND OR LAKE

Typically, 1.6 to 3 feet (0.5 to 1.0 meter) of clay is needed to seal an earth dam. The pond water level naturally fluctuates, resulting in periodic wetting and drying of the pond bed. When the bed is exposed and not submerged under water, the clay layer can crack as it dries and these cracks can go down about 1.6 feet (0.5 meters), so 3 feet (1 meter) is ideal to account for this natural cyclical process.

When enough clay is not available at the site of the pond, we must consider other alternatives to seal the pond bed. The benefits of having a pond for water storage outweighs the use of non-natural materials that may be needed. If a pond is leaking, these methods can be tried – ideally in this order if the goal is minimum effort:

COMPACTING OPTION

- Gleying – sealing with organic material, either with a layer of mashed, green, wet plant material or by allowing cows, ducks, and other farm animals to graze within the pond bed. The bed becomes compacted by their hoof action and as the manure decomposes, it forms a material that naturally seals small cracks. The basic process entails having a layer about 6-9 inches deep of green organic material (either plant or manure) over the pond bed (base and sides) and then covering this layer with soil, cardboard, plastic, etc.. The trapped material begins to decompose anaerobically. In cold areas, allow 1 to 2 weeks. In tropical areas, allow 1 to 2 days. Once the process is complete, remove the layer used to cover the organic material.

BLANKETING OPTIONS

- Imported clay – this is an expensive option. The imported clay can be spread and rolled 9 to 12 inches thick over the entire pond or the area with the potential leak.

- Bentonite ” bentonite* is a clay-powder from volcanic ash that swells when watered and it is this swelling action that seals a pond. When applying bentonite, start with a nice bowl shaped pond with 30 percent slopes and ensure that the surface of the pond bed is rock-free. Then, spread bentonite out thickly and place 1 foot of rock-free soil on top of the bentonite and roll it in. There are two types of Bentonite: 1) Sodium which has high swelling capacity and 2) Calcium with a negligible swelling capacity.

- Impregnated geofabric – When using bentonite impregnated geofabric, start with a nice bowl shaped pond having 30 percent slopes and trench all the way around the outside. Lay out the fabric and put bentonite on the overlapping sections and gravel in the trench to hold the fabric in place. Place 1 foot of rock-free soil on top of the fabric and roll it in. Once the water hits the fabric, it swells up and forms a seal. These come out like a natural swimming pool, they don’t muddy up at all.

TYPES OF EARTH DAMS

There are many different types of earth dams you can construct. This table shows the most common types.

Here are all the good locations we could find for each of the above using a topo map, Google Earth, and 1-square-mile parcel of land.

Note: The Photoshop topo overlay in this image is not as accurate as the Sketchup overlays above and below.

We explore each of these (and a few others) with additional notes and more specific imagery below.

VALLEY DAM

Valley earth dams are constructed across a valley or gully. These dams, sometimes called a “barrier dam,” are most frequently used as energy systems. Especially when built in the path of a flowing or intermittent stream bed. These dams are also valuable for storing large volumes of water, as well as for irrigation. For these dams, it is particularly important to overdesign the spillway and accommodate any fish passage that has been obstructed due to dam installation.

RIDGEPOINT DAMS

Ridgepoint earth dams are located on flattened portions of descending ridges and are quite rare. It is composed of a single, horseshoe-shaped wall. These dams are most useful for water storage and runoff collection.

KEYPOINT DAMS

Keypoint earth dams are located in lower countries where hills transition from convex to concave. These dams are primarily used to store irrigation water and are amenable to being placed in series on descending contours. These are most appropriate for 4-12% slopes.

CONTOUR DAMS

Contour earth dams are located along hillsides where the contour widens on relatively flat terrain (slope of 8 percent or less). They are 3-sided and the front of the dam is either concave or convex to follow the contour. They are most useful for domestic livestock and aquaculture. These tend to be relatively expensive in comparison to their water storage capacity. Like keypoint dams, contour dams are amenable to being placed in series on descending contours. There is insufficient natural catchment so diversion channels or swales are essential.

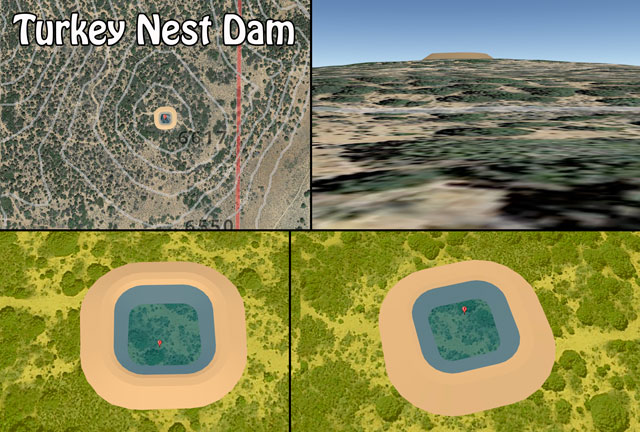

TURKEY NEST DAM

Turkey nest earth dams are earthen water storage tanks best placed on the highest available site with flat ground. These dams do not capture runoff, so they must be filled with external water sources. These are much cheaper than constructed tanks, but limited to use for irrigation, whereas constructed tanks can be used for drinking water as well. These dams should be at least 100 feet x 100 feet x 10 feet (providing approximately 0.6 million gallons of storage) to be cost effective.

SADDLE DAMS

Saddle earth dams are unusual because this type of land feature is rare – a saddle between two hills. These dams have two walls. These dams are most useful for fire control and ecosystem/wildlife support. This type of dam typically ends up being the highest dam on the landscape and has the potential to fill from hill runoff.

BARRAGE DAMS

A barrage earth dam is one of the least likely DIY dams you’d probably consider constructing. This is because they incorporate a large mechanical component to control gates that regulate the amount of water they store. Barrage dams are normally built near the mouth of the river and used to divert water for irrigation needs or limit the amount of water going down-stream. Water builds up behind these dams and a number of large gates are opened or closed to control the amount of water passing through. This allows the structure to regulate down-stream water while also stabilizing river water elevation upstream for use in irrigation and other systems.

Here’s a video about these commonly commercial-scale dams. It provides a good explanation of the difference in function between a traditional dam and a barrage dam.

DIY EARTH DAM CONSTRUCTION STEPS

Here we discuss the steps for constructing your own earth dam. Again, we’re not experts in earth dam design or construction. We’ve just done an immense amount of research on the topic after identifying a need for earth dams as part of the open source One Community Highest Good Housing and Food components. We share here all we’ve learned with the following sections:

Here we discuss the steps for constructing your own earth dam. Again, we’re not experts in earth dam design or construction. We’ve just done an immense amount of research on the topic after identifying a need for earth dams as part of the open source One Community Highest Good Housing and Food components. We share here all we’ve learned with the following sections:

- DIY Earth Dam Planning

- Earth Dam Selection

- DIY Earth Dam Initial Assessment/Site Selection

- Taking Test Slices

- Water Storage Feature Design

- DIY Earth Dam Construction

DIY EARTH DAM PLANNING

Throughout the life of the project, engage in a dynamic thinking process and be flexible and receptive, allowing nature to be your guide. During the planning stage it is important to clearly define the purpose and overall desired outcomes of the project and identify the resources available. Include in your resource evaluation your financial resources, your equipment resources, the lay of the land, and personal and local knowledge base.

- Engage in a dynamic thinking process

- Set your goal to make the land resilient and vital

- Allow your design to change based on findings during construction

- Nature is the ultimate guide, make experiments, use applied knowledge

- Define project goals

- Budget

- Water volume

- Water uses. Ex: drinking, fire suppression, irrigation, etc.

- Identify resources

- Potential supplies

- Favorable slopes

- Elevations

- Key points

- Local construction methods

- Evaluate possibilities using a contour map

- Aridity of the area – Data available from the Global Aridity and PET Database

- Legal ramifications: Meeting with the local watermaster, local county authority for land use permitting, fish and wildlife services, and/or the state for permission can take 6 months or more.

Earth dam construction involves significant risks, including structural failure, environmental damage, and legal issues. Engaging engineers and complying with local regulations is essential to mitigate these risks, ensuring the project’s safety and sustainability while protecting downstream communities.

Earth dam construction involves significant risks, including structural failure, environmental damage, and legal issues. Engaging engineers and complying with local regulations is essential to mitigate these risks, ensuring the project’s safety and sustainability while protecting downstream communities.EARTH DAM SELECTION

When working with nature, it is imperative to have a variety of applications that serve the same or similar end uses. With a water retention landscape, it is wise to have a mixture of earth dam types to meet your end-use needs. This is safer and usually easier. It also better prepares you for unpredictable natural events, such as seasonal and intraseasonal extreme weather variations. To select the appropriate number and types of earth dams, the following table can be utilized:

Here are some additional guidelines:

- Observe the existing patterns of water movement

- Assess climate and topography to determine water potential

- Seek to work with and amplify the site’s natural characteristics

- Assess prevailing winds – they increase losses due to evaporation

- Aim to have multiple earth dam types to serve a variety of end uses

- High potential-energy dams: located high up, such as keypoint and ridgepoint dams

- High water volume dams: located on gentle slopes, such as valley dams

- Maximum value for money and effort spent is achieved when the resulting length of water retained behind the earth dam is 3x the length of the dam wall

DIY EARTH DAM INITIAL ASSESSMENTS/SITE SELECTION

It is crucial to have soil with sufficient clay content for the earth dam structure, as well as the pond bottom. Soil with at least 40 percent clay is necessary to build a water-tight earth dam, and to retain water in the pond. Given the importance of this criteria, it is worth the money to rent an excavator to dig and evaluate the soil at the potential earth dam sites identified in the step above. The “Taking Test Slices” section below discusses how to do this.

Use models and small experiments to more deeply understand the local landscape’s potential for water storage. It is very hard to work with free-draining soil (deep or coarse sands), rocky areas, and/or areas too steep or unstable. The bottom of gentle slopes are usually better choices.

If clay has to be brought in (versus mined on your own property), rethink the pond location and/or water storage method.

TAKING TEST SLICES

Taking test slices helps you understand the types of soil you will be dealing with. Using an excavator (if available), assess the geology 6 to 12 feet below the ground surface at around 6 different locations. You can go as deep as 15 feet, but beyond that returns diminish. Dig until an impermeable layer is reached near the depth you want your pond to be. This article called “soil permeability” explains well what you are looking for and why.

The geology can be significantly different just 30 feet away. In some areas it is helpful to have the excavator put each scoop in sequence so each layer can be assessed for clay content. The excavated materials (called the “overburden”) may need to be sorted to arrive at the correct clay content. Forty percent clay or more is the goal. If you don’t have 40 percent or more clay, another area on the property may need to be mined. The video below shows how to test and measure your clay content.

Note: For earth dam construction, it is preferable to use test slices over coring. This is because coring typically only provides an assessment for the first 3 feet below the ground surface and you are seeking to assess your soil between the depths of 6 and 15 feet.

Testing Soil for Clay ContentWATER STORAGE FEATURE DESIGN

Earth dams may not be the ideal solution for all locations and there are many different kinds of earth dams (see “Types Of Dams” above). Here are the key guidelines our research identified:

- Seek to minimize earth dam size

- Seek to maximize water retention

- Look at the resources you have

- If you have a valley, pick the narrowest point

- Minimize earthwork and disturbances/maximize undisturbed areas

- Use models and small experiments to test your ideas before starting construction

- Keep your thinking process dynamic/be open to change

- If you have to bring in clay, then rethink your pond location and/or water storage methods

- It is ok for your earth dam and water reservoir to leak, because subsurface and surface runoff are filling the pond

- If using your pond for fire suppression or irrigation, place the pond 100-250 feet above your area to irrigate/protect so it can function without electricity. For fire suppression, talk with the fire department to outline the exact place, including access and fittings.

Sepp Holzer uses a water-retention-landscape style where the surrounding forest is your water reservoir. Water from your dammed area spreads through the surrounding ground and helps develop a lush landscape. The picture and video below are about one of Sepp’s earth dams and the landscape like this that he created.

Tamera Eco-Settlement Water Conservation Results: This Took Less Than 4 years

WATER IS LIFE - The Water Retention Landscape of TameraDIY EARTH DAM CONSTRUCTION

A successful water retention landscape can be created using basic principles and well-established parameters. At a minimum, a water retention landscape consists of earth dams, embankment ponds, spillways, and erosion control interventions. On some landscapes, sediment traps, diversion drains, and swales make sense. In simple terms, assure that the local soil has at least 40 percent clay, all earth dam walls can be less than 20 feet (6 meters) high and still meet minimum volume/end-use requirements, and that the pond length behind the earth dam is at least 3 times longer than that earth dam’s length. An expanded array of details is provided in the image and text below:

A successful water retention landscape can be created using basic principles and well-established parameters. At a minimum, a water retention landscape consists of earth dams, embankment ponds, spillways, and erosion control interventions. On some landscapes, sediment traps, diversion drains, and swales make sense. In simple terms, assure that the local soil has at least 40 percent clay, all earth dam walls can be less than 20 feet (6 meters) high and still meet minimum volume/end-use requirements, and that the pond length behind the earth dam is at least 3 times longer than that earth dam’s length. An expanded array of details is provided in the image and text below:Below are our notes taken regarding the main features shown in the image above:

EXCAVATION

- It’s a good idea to strategically place excavated material in locations where they will be used.

“Wherever you are doing earthworks, you need to carefully remove the topsoil and not conglomerate topsoils and subsoils together. It’s taken 100s or 1000s of years to make that topsoil, you’re not going to make it again too easy. Separate it and then make your shapes and forms.”

~ Geoff Lawton ~EARTH DAM STRUCTURE

- With 10-foot (3-meter) high earth dams made of 50 percent clay, there is confidence in the structural stability. We came across statements that 40 percent clay content is also good and can go as high as 20 feet (6 meters) tall without consulting an engineer. We’d always suggest an engineer though.

- Keyway should tie into the parent clay layer to cut off subterranean water flow and may need to go 13 to 23 feet (4 to 7 meters) down, but any deeper could cost the job. Meaning, if there isn’t clay after you have dug 23 feet, then it could be too costly to keep digging and you should consider exploring alternative methods and/or other ways to seal the pond.

- Inside wall should have at least a 1:3 slope.

- Outside wall should have at least a 1:2 slope.

- You can build your earth dam slightly concave for added stability and the earth dam will naturally take that shape over time.

- Suggested to have your crest wide enough to drive a tractor across it.

- Top dress the earth dam wall from the waterline on the water side, over the crest and down the entire backside. This adds a layer of healthy, organically rich soil that plants can grow in, which adds stability to the system.

- A lot of water builds up on the back of a dam, typically saturated, with lots of potential to support plant growth. Be prepared to be ready to seed when earth work is done.

- Plant vegetation with shallow roots (such as bamboos and grasses) and avoid deep-rooted and water-hungry plants. Bamboo sits well on the back of the wall, and on the water side of the wall above the freeboard, as well as on the opposite side of the dam. Avoid plants with taproots, like acacia. Bamboo is also a natural weed preventer, as you will only find bamboo leaves that are slow to decompose and high in silica around bamboo groves. You want to keep plants around the dam small, if it is too big to take down with a machete and a chainsaw is needed, then you have let it go too long, and need to remove asap.

- When stripping the top soil off, hold it as high as possible, because it is easier to move the soil downhill as opposed to pushing it uphill when redressing the dam wall to plant stabilizing vegetation.

- When moving earth, you have to do something with the roots – they are massive and hard to move with conventional farm equipment, so it is important to move when earth movers are there. One option is to just mound the roots and paper mulch all around the roots, and plant pioneer and hardy trees around the mound, and then plant perennial ground cover that is easy to maintain, like legumes and sweet potatoes. This gets stumps out of the way so you don’t accidentally run into them when trimming and mowing the property. The mound of roots gets an entire ecosystem going on their own. A whole lot of habitat developed in the roots. Another option is to have an old stump in the middle, and trim around the stump. If the stump happens to be hollow, you can fill up with good soil, and plant avocados. Avocados like 4 feet of well-drained soil. Over time the stump degrades.

MATERIAL USED TO BUILD EARTH DAMS

- Build with material that is slightly damp. You should be able to make a ball with it that holds together and does not expel water.

- If possible, start your project when your soil has the right moisture, otherwise build during the dry season and bring in fire trucks for water.

- Avoid: anything larger than an orange, logs, top soil, and/or clumps of grass.

- If good clay-content material is limited, use the best material on the water side and not-so-good material on the back side. The water side of the earth dam needs to be watertight, but the outside of the earth dam does not.

KEYWAY

- Track roll the earth dam keyway and wall every 200 mm (7 inches). The basic process is to lay out soil about 200 mm in depth. Then to pass over the soil again and again until depth is about 6 inches (150 mm). If using a sheepsfoot roller, this takes somewhere between 6-12 passes at a roller speed of 2-4 mph (3-6km/hr). This Manual on Small Earth Dams (PDF) has information on compaction requirements on Page 63 and says the following: “Farm machinery (e.g. tractor tires filled with water following a staggered track or small rollers) and hand methods are usually only sufficient to successfully compact layers 3 to 4 inches (75-100 mm) deep. Heavier plants such as sheepsfoot rollers (ideal for clayey soils), vibratory and smooth wheeled rollers (ideally for sandy soils) can work with layers up to 200 mm thick and obviously are preferable where large quantities and widths require compaction.”

- Since you are compressing, you will need more soil than you think.

WATER FEATURE

- Search for a good clay layer, you know you have found it when the layer is hard to dig through – no tamping necessary.

- Align water features in the direction of your prevailing winds.

- Your pond/lake can be 5 to 6.5 feet (1.5 to 2 meters) deep.

- Aim for a minimum of 3 feet (0.9 meters) freeboard.

- Your water feature can take a long time to fill up – the ground underneath has to become saturated.

SPILLWAY

- Over design your spillway, it needs to quickly get excess water away from your dam.

- Design for 1000-year storm since we are moving into severe weather due to global warming.

- Make your spillway wide, flat, and shallow.

- Build on undisturbed subsoil.

- Avoid steep sections.

- Your spillway opening should be 1.5 feet (½ meter) below the lowest point of the earth dam.

OVERFLOW

- Use an overflow pipe to keep your water level constant.

- Make sure you also have secondary overflow control.

- At least a 6-8 inch diameter pipe is recommended, not much smaller.

- Monk pipe design notes (from Geoff Lawton Permaculture 6&7 video – timestamped 6:26:00): Used as a water level control valve, as well as serving as an overflow. Blitz cement/C900 pipe/belled 90, remove gasket on straight part of joint to be able to pivot, ok if it leaks.

EROSION PREVENTION

- Maximum angle of repose for terraces is 1:1.

- Maximum angle of repose for land in contact with water is 1:2 in all directions.

- Vegetate/mulch the banks or secure with tight rows of Vetiveria Zizanioides.

OTHER ATTACHMENTS

For desert landscapes, have your silt (or sediment) trap above the main water feature.

- Can be a deep pond filled with gravel and plants with roots underground and heads above, such as reeds.

- Be sure you have easy access to your sediment trap so it’s easy for an excavator to dredge.

You can put in other attachments too. Examples are swales (tree-growing systems), ledges for plants, and/or deep-water refuge for fish in areas where water freezes.

- Diversion drains/ditches are giant earthen gutters to move water like a rain gutter.

- Swale built on permeable soils – slowing, spreading, sinking water across the landscape.

Wherever you are in the business of making swales, work out how big they ought to be, then triple it. If they’re going to be a meter wide and a meter deep, make them 3 meters – 4 meters wide, and 3 meters deep and you might hold those big events. But if you don’t, it’ll blow the lot out. If your top swale blows, then the bank goes, and all your other swales go.

~ Bill Mollison ~DIY EARTH DAM CONSTRUCTION CASE STUDIES

Two case studies are presented below from work completed by Geoff Lawton. These are from the Permaculture Design Course DVDs where he taught with Bill Mollison. One key takeaway from both is placing emphasis on making things very level, so water flows will soak passively and carry nutrients around the property. We’ll add our own case studies here with videos, much clearer explanations, and complete tutorials as we complete our own dam constructions as part of the 7 sustainable villages.

DIY EARTH DAM CASE STUDY #1

The first case study presented is Lawton’s permaculture property that he eventually sold to one of his students. The property is located North of Brisbane, Australia on the sunshine coast where it rains quite a bit. The property is 5 acres and zoned as a small farm, about half forested and half farm fields. The forested area was inaccessible because of a valley with a creek running through it. There are three creeks on the property:

- The main creek receives 200 acre-ft of water and is located in the valley that divides the forested land from the farmland

- The secondary creek receives about 50 acre-ft of water and is located in the forested area

- The third creek originates on the property

Lawton completed the work successionally – taking approximately ½ of his time for 2 years. An image of the work (dams, swales, and roads) is shown in the screen capture below from the video where he discusses this case study:

DIY Dam Case Study – Geoff Lawton’s Brisbane, Australia Property

The first thing Geoff did was install a dam to gain access to the forested side of the property that was originally deemed unusable – the road over the dam is what allowed access. A serious 8-meter wide spillway was also installed that fed back into the primary stream. It was big to minimize the erosion potential to the dam wall. During big rains, 1 meter of water would go over the spillway. A pump was installed with a float and weighted foot valve to transfer water to the top of the property. The inlet to the pump was held below the water surface with a weight and off the floor of the dam with a float. The next two were placed in succession on the secondary creek with the spillway of the upstream dam feeding into the dam in series and the second dam fed into the third stream that originated on the property. Lawton believes that replacing 20-year-old growth forest with bodies of water is beneficial because life is boosted by increased water retention.

When a wet spot was noticed at the top of the property, a contour dam (also called a top tank) was installed. It was supplied partially by the road and nature strip. Its spillway drained into multiple swales on-contour that were in-series to direct the water around the farm field. This contour dam had geese and ducks, which resulted in nutrient-rich water. When water is released during the dry season, it takes a couple of days to soak into the dry ground, then it only takes a few hours to soak the land with nutrient rich water.

Then in the bottom corner of the property, it started to get boggy after about 6 months. A neighbor began complaining about this effect, so Lawton dug a trench 2 meters wide, 1 meter deep and put the excavated material on the downhill side. When earth movers hit clay in the trench, they compacted it by hitting it with the back of the bucket. This half circle pond filled quickly. After this, a third large swale was added to further disperse the water throughout the property. Lawton hand-dug 8 to 10 meters every day for about a month and the swale ended up being more accurate than the excavator.

The neighbor continued to submit complaints and caught Lawton on a technicality, which led Lawton to improve upon his design even further. Lawton was not allowed to divert any flow from the secondary stream to the third stream. This led to the addition of another contour dam on the third creek that was connected to the dam on the secondary stream using a canal (angled banks going down to a flat bottom). Two spots were picked that were the same elevation to have easy control over the direction of the water flow. The lower dam wall was extended to cover both the secondary and third creek, which created yet another pond at the third stream. Mounds and swales were used to direct extra water into the third creek and with a slight height difference and sluice gate to direct water back to the secondary stream, so no water was being diverted from there.

Beyond this work, Lawton also had small swales near the simple temporary home near the gardened (bamboo and legumes) area for kitchen flows. These swales were 2 meters across, 1 meter deep and with 2 meters across and 1-meter high mounds. Graveled footpaths were also added between the gardens off the lower-corner dug pond, where water had been pooling near the neighbor’s property. Because the footpaths were next to the pond, they were partially flooded with water. He trellised over the pond and grew trees on the mound next to the pond and used water weeds as mulch for the garden. The last addition was a ridge point dam, which was the 7th body of water added to the property. Lawton essentially confused the catchment, melded them together and while he fixed one problem, he technically caused another problem, but creatively fixed that too. In the end, Lawton achieved the goal of having 15% of the property under water.

DIY EARTH DAM CASE STUDY #2

The second case study was a consulting project that Lawton worked on located in Clunes, Northern Wales. It was a hilly project serving as a demonstration and teaching site. The work completed included building two dams, a large lower valley dam and a small upper contour dam.

The entire process began with a plan on a good contour map. In the lower one, a mix of bad soil and clay were found, so earth workers and their machines had to find better material elsewhere on the property, as well as blend dirt together to attain the appropriate clay-content necessary for the keyway and water-side of the dam wall. This was especially important to do because the lower dam had a decent flow and catchment area to it. Valley dams, like this one, are important to seal.

The lower dam was built with a Jetty too. Jetties have to be pre-built before the dam is filled with water. These provide a clean edge to the dam and somewhere peaceful to sit. The top of the dam was also a minimum of 3.5 meters wide so tractors and other average-sized machines could go across it to trim growth or do other work. Topsoil was placed (it is like icing a cake) on the waterline and then hydro mulched with seed (i.e. sprayed with wet mulch containing seed). The hydro mulch contained pioneer trees, bushes, and cover crops, along with organic glue and shredded paper.

The lower large dam used a large spillway swale with level sills and was installed by ripping the soil with a tilted blade on contour. All heights were checked with a laser level (laser level emitter on tripod and laser receiver – earth movers sometimes have these for rent) and considered adequate when within 10 mm. The elevations were marked before starting and double checked along the way and at completion. To achieve clear water (the clarity of a dam at best is usually weak tea type of clarity), he installed three silt trap ponds before the dam and made sure the edges were well vegetated.

This second dam was installed 20 meters above the house and acted as their water tank. A dam holding about 125,000 gallons is less than half the price of a tank holding that same volume. It is more economical to build a key point dam on top of the property.

Notable comment from this case study: It can be surprising what you find when you start digging. You never quite know what you are going to hit. If you hit a big rock and you don’t know how big it is, have the bulldozer bump/ram (as hard as he can) the rock while you stand next to the rock. If the ground shakes, then it is a floater, meaning it has a bottom and you can typically move the rock out of the way or work around it. If there is no shake, the rock is part of mother earth. Earth moving contracts usually mention OTR, which stands for Other Than Rock, because rocks are hard to deal with and hard on the machines.

DIY EARTH DAM COST ANALYSIS

Conducting a thorough cost analysis is essential to assess the financial feasibility of a dam project. The methodology for estimating costs and the expected range of accuracy will vary depending on the project’s stage of development and intended use. For projects at different maturity levels—such as conceptual, preliminary, or detailed design phases—specific estimation techniques are applied, each offering varying degrees of precision. One of the most commonly used methods in engineering projects is unit cost estimation, which assigns a cost per unit of work (e.g., per cubic meter of clay materials). As the project becomes more defined and detailed, the estimate evolves to include more precise line items, often at the assembly level, along with take-off quantities for greater accuracy.

However, several factors can introduce biases or uncertainties into cost estimates, including the quality of reference data, assumptions about key variables, market conditions, construction timelines, and the estimator’s experience and expertise. Therefore, a careful and critical evaluation of these factors is required to minimize estimation errors and ensure the project’s financial viability is accurately assessed.

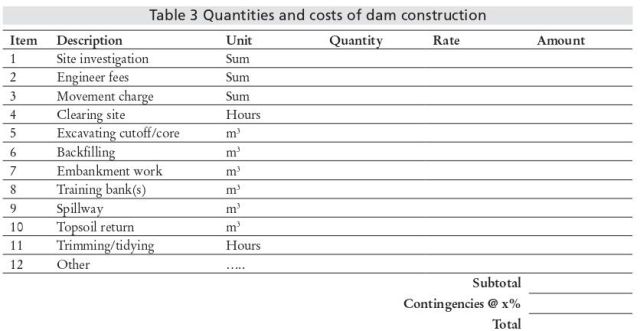

The Manual on Small Earth Dams provides a table detailing various items essential for conducting a cost analysis. With the preliminary dam construction design in hand, users can utilize this table to assess expenses effectively. The items are categorized as follows: the first three belong to the preliminary and design phase. This phase includes expenses such as permits, land acquisition, and other necessities required to proceed with construction. The following items are classified as direct construction costs, reflecting expenses directly associated with the physical construction of the dam. It’s important to note that additional items may be included based on the specific circumstances of the project.

At the bottom of the table, the “contingencies” box, which requires entering a percentage, serves to provide a financial buffer against uncertainty. The contingency amount can be determined using methods such as range estimating, as introduced by the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering (AACE).

EXAMPLE OF HIGH-LEVEL COST ANALYSIS

The report provides high-level (low accuracy) cost estimates for various dam storage configurations within the Hughenden Irrigation Project, facilitating the evaluation of infrastructure needs against changes in dam yield to identify optimal storage solutions. In the cost section, alongside previously mentioned items, key factors such as miscellaneous costs, general expenses, contractor profit, and taxes are also discussed. Given the limited available information, costs are estimated based on certain assumptions, such as calculating them as a percentage of direct costs. This approach is common in the early stages of planning and design, though it may lead to unavoidable inaccuracies.

COST CURVE OF SMALL DAM

For typical dam designs, online resources, such as reports from the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE), provide a cost curve that estimates the costs associated with small rock-fill dams and three types of concrete dams. This cost curve facilitates easy estimation based on dam height and length. The cost curve is derived from specific unit prices and accounts for 20% in preparing and running costs. However, it is important to note that the cost curve is based on certain assumptions, was developed several years ago, and reflects conditions specific to Norway. As such, it may not accurately represent current situations in your project area. Therefore, while it can serve as a rough estimate, a detailed cost estimation is still necessary for your specific site and design.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Cost analysis in dam construction is complex and subject to numerous site-specific and external factors. Several key factors need to be carefully considered, particularly because the nature of dam construction is heavily reliant on civil engineering work, which varies significantly depending on site conditions. For example, remote sites tend to incur higher transportation costs due to the challenge of delivering materials, equipment, and labor over longer distances. Additionally, sites with complex geological conditions lead to increased construction challenges, raising the overall costs due to the complexity of the engineering work.

Research on dam costs and overruns shows that cost overruns are more significant compared to other construction projects. A key factor identified is the length of the construction period. Longer projects are often more complex, harder to plan for, and more vulnerable to inflationary pressures, making accurate long-term cost estimation particularly challenging.

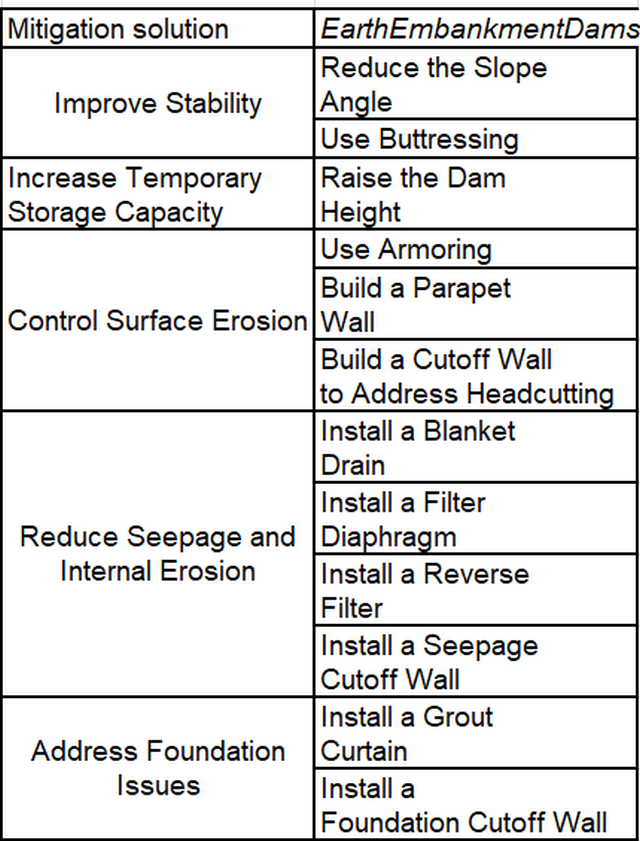

DIY EARTH DAM DISASTER RISK MITIGATION

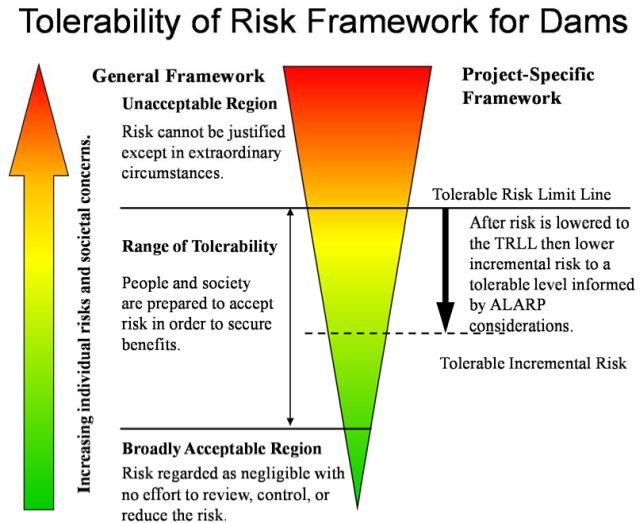

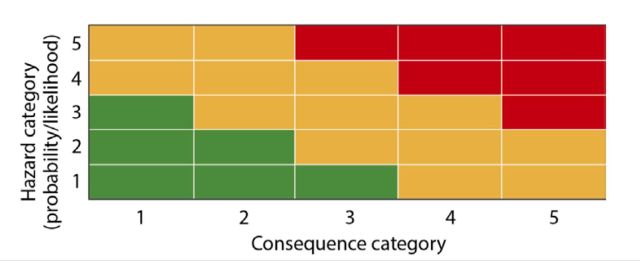

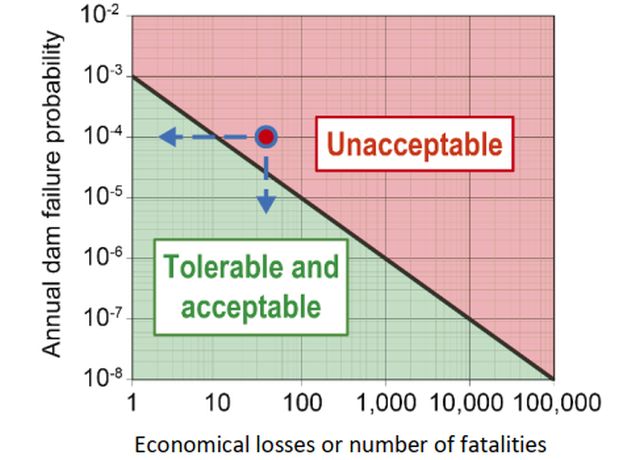

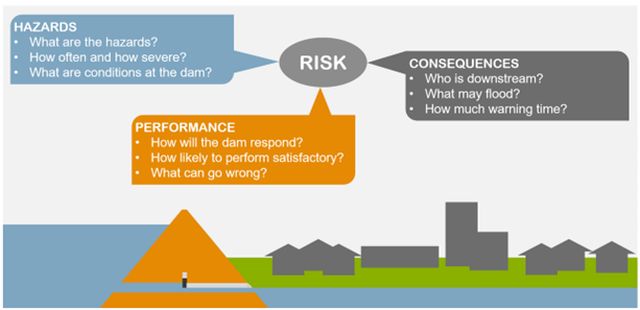

“Risk = Probability of Dam failure X consequence of Dam failure”

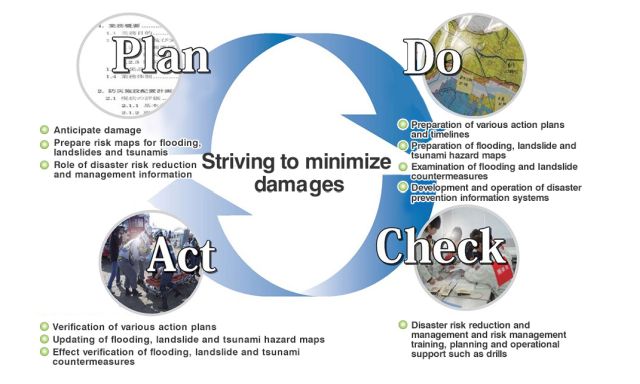

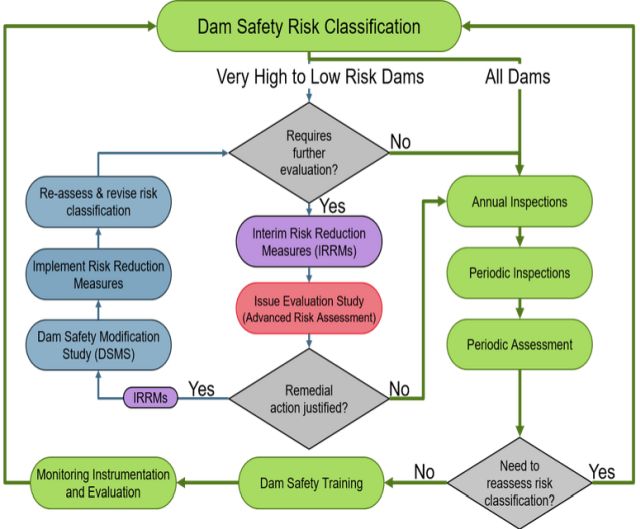

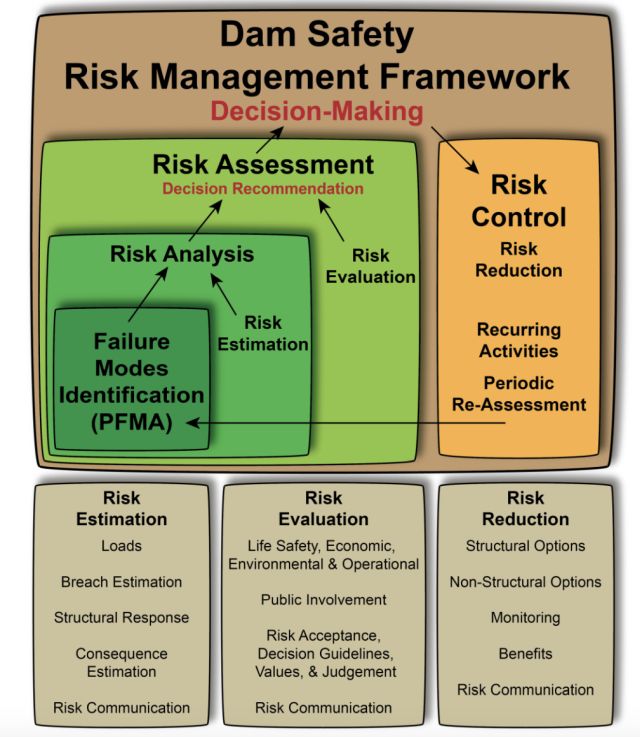

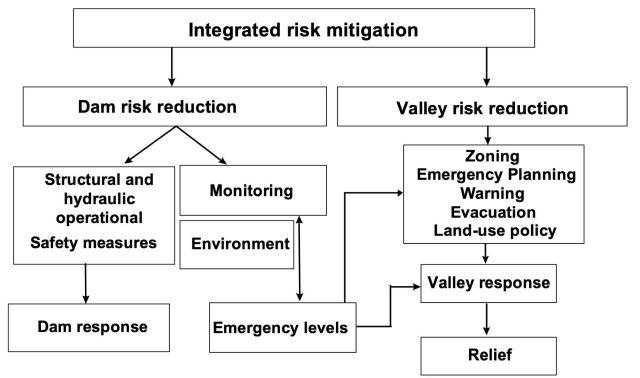

The purpose of risk assessment is to help people and organizations better understand the various measures that can be taken to reduce the risks of and improve resilience to dam failure. These measures can be taken by individuals, dam owners and dam operators, organizations, communities, relevant state and local agencies, or tribes. This section provides an overview of the risk reduction measures for consideration and use based on individual situations and provides resources with more information.

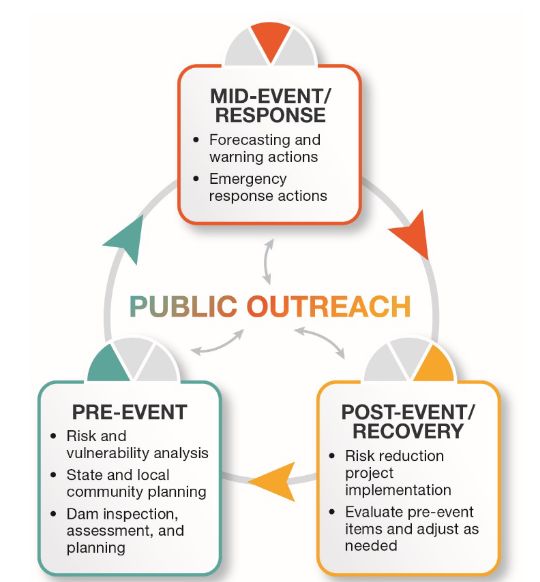

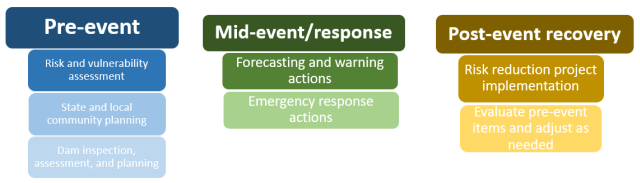

Risk reduction measures aimed at reducing the likelihood of a dam failure and improving the resilience of those impacted by a potential dam failure should be tailored to the needs of all stakeholders. Stakeholders must understand their roles and responsibilities to ensure effective risk reduction and incident management. One of the initial critical steps is identifying the at-risk population and understanding each stakeholder’s mission, objectives, obligations, and expectations for risk reduction. Ensuring effective communication among stakeholders will improve coordination among the various entities, particularly following a dam failure. The actions can be categorized according to the event scenarios as seen in the image below.

Earth Dam Risk Mitigation Chart

We go into further detail about dam disaster risk mitigation in the following sections:

- Pre-Event Planning

- Mid-Event Actions

- Post-Event Recovery

- Detection of a Hazard

- Warning the Population at Risk

- Dam Safety Guidelines and Inspection Procedures

- Dam Safety Inpection Program

- Comprehensive Evaluation Inspections

- Dam Problems, Causes, Consequences & Recommended Actions

PRE-EVENT PLANNING

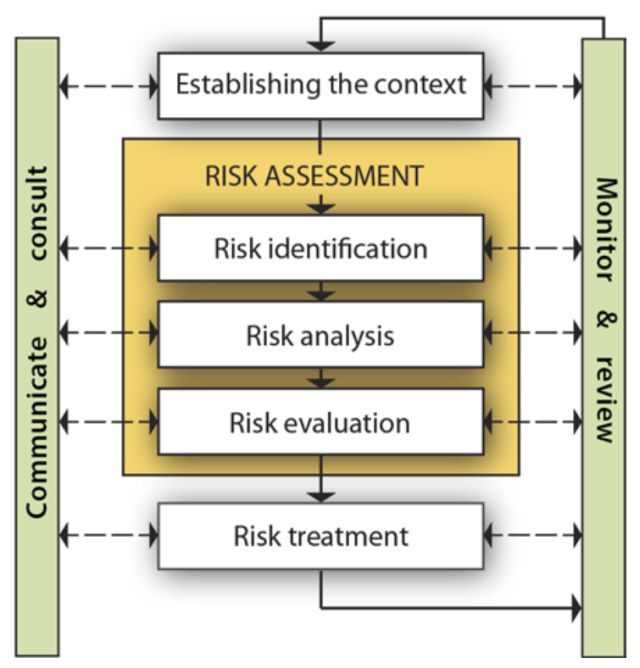

Many entities from federal to local are involved in and responsible for dam safety planning activities. These activities serve a wide variety of purposes, from long-term resilience to short-term emergency response. Many types of stakeholders may find it advantageous to conduct a risk assessment. A risk assessment identifies potential hazards and analyzes what could happen if a hazard occurs. The methodology and information included in the assessment will vary depending on hazard types and mitigation measures used in the pre-planning processes.

It is important for those involved in risk management of dams (owners, regulators, state and local officials, and individuals, among others) to understand the all necessary actions to ensure dam safety and the extent of the evacuation needed for particular scenarios. An evacuation may be triggered by a catastrophic dam failure, but it could also be necessitated by the activation of an emergency spillway. Both scenarios may have different inundation and evacuation maps. Details related to different failure scenarios and dam releases should be outlined in the Emergency Action Plan (EAP) / Emergency Operations Plan (EOP). All appropriate stakeholders should be involved in dam safety and crisis response.

Important Terminology – As defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)- Hazard ” Natural, technological, or human-caused source or cause of harm or difficulty (FEMA, 2010).

- Threat ” Natural or manmade occurrence, individual, entity, or action that has or indicates the potential to harm life, information, operations, the environment, and/or property (FEMA, n.d.)

- Vulnerability ” Physical feature or operational attribute that renders an entity open to exploitation or susceptible to a given hazard (FEMA, 2010).

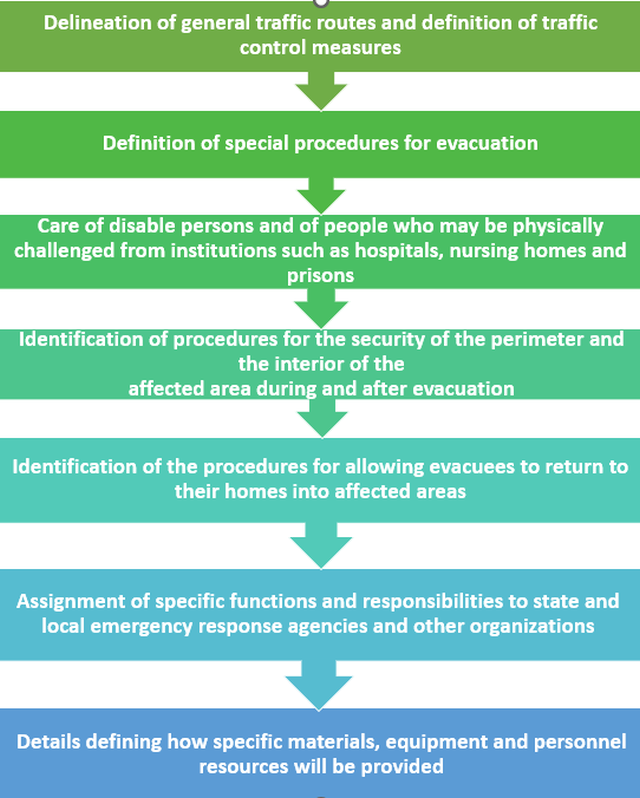

DIY EARTH DAM PLANNING ACTIONS

Planning activities, including developing an Emergency Action Plan, should be performed by dam owners and operators. Serving a wide variety of purposes, from long-term resilience to short-term emergency response, many entities are involved in these activities.

The following advisory presents several suggested planning activities. However, it is not intended to be inclusive of all planning that could be performed by stakeholders to reduce the risk of a dam failure, prepare for potential dam failures, and improve response and recovery activities should such an incident occur.

Suggested Types of Planning Actions (source):Preparedness

- Develop pre-disaster Memorandums of Agreement and/or Memorandums of Understanding with adjacent jurisdictions.

- Gather information from risk and vulnerability analyses, dam EAP, dam failure inundation maps, and state or local hazard.

Operational

- Prepare for mass care (sheltering, feeding operations, emergency first aid, bulk distribution of emergency items, and collecting information on victims and providing it to their families).

- Test and evaluate pre-disaster plans through exercises (e.g., tabletop exercise, functional exercises).

Mitigation

- Determine whether critical or essential facilities require mitigation and retrofitting such as wet or dry floodproofing.

- Voluntarily move, remove, or elevate already-existing structures and restrict new development in the dam failure inundation zone.

Security

Zoning

- Review hazard creep regularly.

- Review and update zoning as needed.

Emergency Operations

- Include evacuation maps in the EOP. Evacuation maps are used by emergency management personnel to notify the public and evacuate areas potentially affected by an emergency.

- Evacuation maps should show information such as road closures, detours, and shelters to facilitate the timely evacuation of people.

- Emergency management personnel can also adapt inundation maps to facilitate evacuation procedures by adding features such as highlighted evacuation routes and emergency shelters.

An Emergency Action Plan (EAP) is vital for every dam to ensure a swift response in emergencies. Effective communication and coordination among emergency management agencies and stakeholders are key to minimizing damage and saving lives. Regular training and inspections are crucial for preparedness.

An Emergency Action Plan (EAP) is vital for every dam to ensure a swift response in emergencies. Effective communication and coordination among emergency management agencies and stakeholders are key to minimizing damage and saving lives. Regular training and inspections are crucial for preparedness.DIY EARTH DAM EMERGENCY ACTION PLANS

Every dam should have an Emergency Action Plan, regardless of their hazard potential. An EAP is a formal document that identifies potential emergency conditions at a dam and specifies actions to be followed to minimize the loss of life and property damage.

Emergency Action Plan

- Emergency protective measures.

- Monitoring procedures during incidents.

- Inundation maps, which show the areas that would be flooded if a dam failed.

Conduct Training

- Train personnel in monitoring and inspection procedures for the dam.

- Train staff to understand the instrumentation used at the dam, how to interpret the data, and typical seasonal trends so they can notify the dam owner of abnormalities.

Conduct Dam Inspections

- Review the latest inspection report.

- Complete a thorough inspection of the dam and appurtenant features to assess their operation and condition.

- The frequency of inspections depends on dam conditions.

Conduct a Dam Evaluation

- Review the latest inspection report.

- Perform a desktop review of changes in recommended practices.

- Determine whether a specific dam evaluation is needed (e.g., seismic).

- Evaluate conformance to current engineering standards and dam safety requirements and upgrade the dam to meet the appropriate standards as needed.

Perform Operations and Maintenance

- Properly maintain the dam and follow a comprehensive maintenance schedule to ensure that elements are repaired before they become problematic or expensive to fix.

- Perform needed repairs.

- Consider installing instrumentation and establishing a corresponding monitoring program when warranted

Perform Needed Mitigation

- Adding redundant or improved operational systems for complex dams.

- Adding interim risk reduction measures to reduce risk until permanent solutions can be funded.

- Decommissioning and removing the dam to eliminate dam-related hazards if the dam is no longer needed or outlives its benefit.

DAM HAZARD POTENTIAL CLASSIFICATIONS

Dam hazard potential classifications are important to know because the hazard potential classification may impact the mitigation solution. The possible classifications include low hazard potential, significant hazard potential, and high hazard potential. They are each defined as the following:

- Low Hazard Potential ” Dams where the failure or mis-operation results in no probably loss of human life and low economic and environmental issues

- Significant Hazard Potential ” Dams where failure or mis-operation results in no probable loss of human life, but it could cause economic loss, environmental damage, disruption of lifeline facilities, or impact other concerns

- High Hazard Potential ” Dams whose failure or mis-operation results in probable loss of human life

MID-EVENT ACTIONS

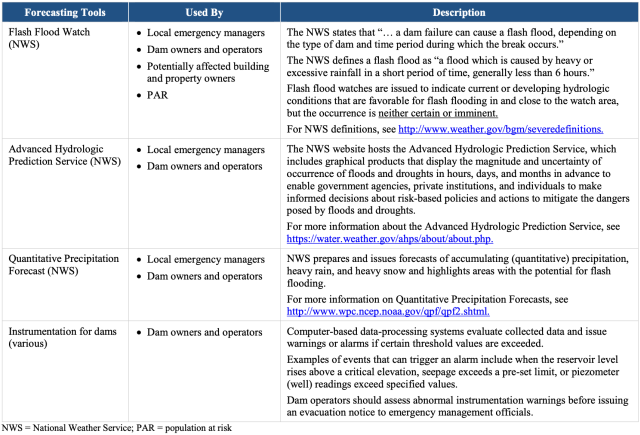

Forecasting and pre-emergency warning systems and emergency action for dam owners and operators can be used.

POST-EVENT RECOVERY

Post-event data are especially critical for risk assessment. To be better prepared for a dam safety incident, stakeholders can improve their understanding of potential consequences of an incident, including an

unplanned large reservoir storage release or failure scenario for a particular dam and the probability for a given event scenario (e.g., mechanical failure; inoperative gate or valve; trash rack or inlet clogging) at that specific dam. Post event recovery can be done by collecting accurate data that provides additional insight to the dam’s design, condition and performance, and effects on downstream assets by:- Verifying inundation models Updating/refining dam breach parameters

- Comparing observed width and depth of breaches to equation-based estimates

- Evaluating failure mode(s)

- Refining failure/breach analyses for developing Emergency Action Plan inundation mapping

- Obtaining water depths at the inundated areas of failed dams

- Using lessons learned to prepare for the next event

- Obtaining high water marks to help determine water surface elevations at the upstream and downstream faces or left and right abutments of breached or overtopped dams

With this information, dam owners can develop dam-specific plans and establish memorandums of agreement so they are better prepared to respond to emergency incidents. In addition, communities can include this information in mitigation plans, land use plans, a dam-specific annex to their Emergency Operations Plan

There are some evaluation conducted as part of post event learning, particularly related to improving emergency performance for future events.According to the research study, there are five main types of formal post-event emergency management evaluation.

- After-action review and operational debriefs

- Community meetings/debriefs

- Community surveys and other social research

- Government inquiries and reviews

- Independent evaluations

Measures considered are those that fall under FEMA’s Category B Emergency Protective Measures.

Emergency protective measures conducted before, during, and after an incident are eligible if the measures eliminate or lessen immediate threats to lives, public health, or safety OR eliminate or lessen immediate threats of significant additional damage to improved public or private property in a cost-effective manner.

DETECTION OF A HAZARD

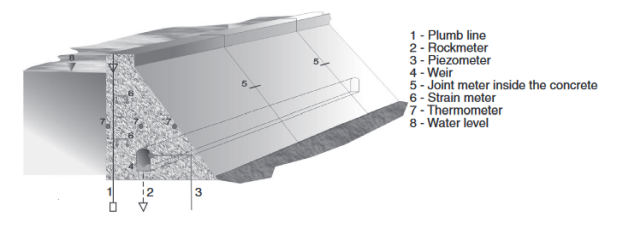

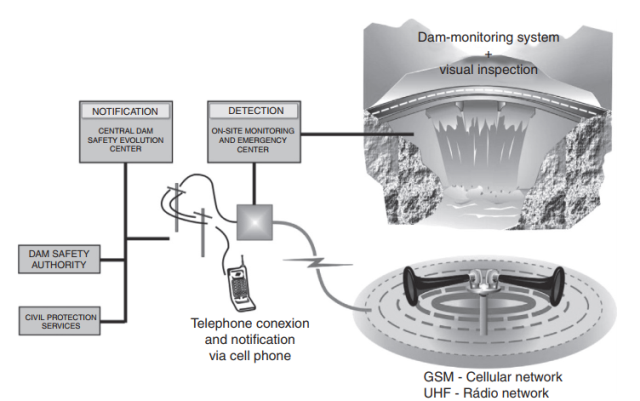

A successful dam safety monitoring system consists of the following four components:

- Visual inspections

- Instrumentation

- Data collection

- Data evaluation and management

This system is ultimately utilized to detect any possible threats to a dam infrastructure, such as floods and landslides.

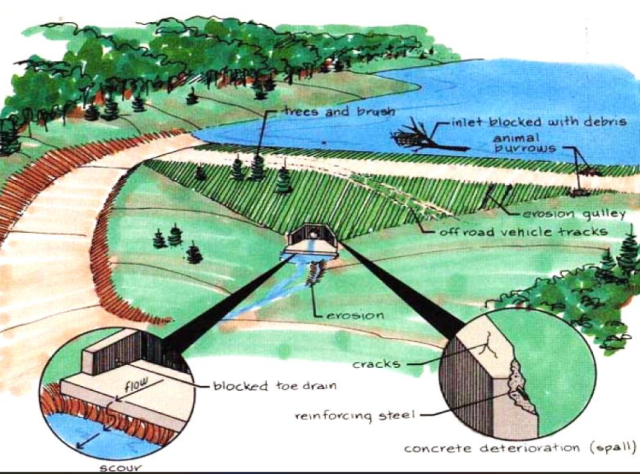

VISUAL INSPECTIONS

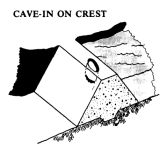

Visual inspections are a key factor in a dam safety monitoring system. In fact, there are a lot of situations, like the evolution of an important crack, which can only be evaluated through visual inspections.

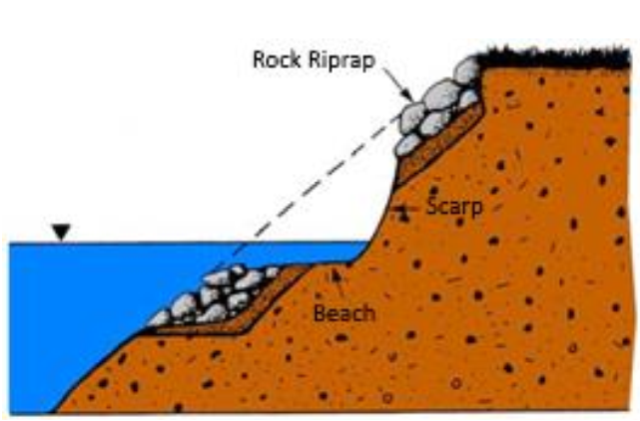

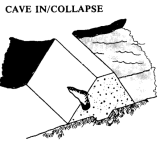

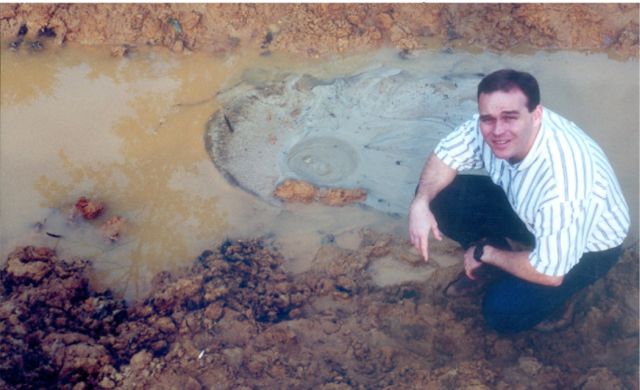

The engineers check for cracks, bulges and hollows on the upstream and downstream face. Just like landslide the dam could indicate unstable, and there is a possibility that with time, a portion of the slope could collapse. Hollows can also indicate that floodwater has been over topping the dam and gradually eroding the downstream slope. Engineers check signs of water leakage through or under the dam. Leakage through the dam can erode away the material inside gradually creating a large cavity. Eventually, the cavity can collapse in on itself reducing the stability of the dam.

Nowadays new technologies are adopted for a better visual inspection of the dam. Combined laser scanning and digital image technologies are recent fields of research and the use of such technologies will certainly enable the automation of visual inspection data collection. Moreover, this calls for an effective implementation of a visual inspection support system which will enable the identification of deterioration processes in a rather accurate, complete and faster way.

INSTRUMENTATION

The instrumentation component of a dam safety monitoring system includes sensors for the measurement of key parameters that can be used to monitor the ongoing performance of the dam.

Sensors must be installed in order to undertake the following recommended measurements (Tavares de Castro [28]):

- Temperature

- Seepage, flow, and uplift pressure

- Displacements

- Strains and stresses

- Accelerations

DATA COLLECTION

Data collection can vary from manually read instruments to fully automated data acquisition systems. The most appropriate data collection system depends upon the dam safety monitoring objectives. A typical dam safety monitoring system consists of a small number of measurements with fully automated data acquisition, sufficient for allowing a fast and efficient evaluation of the dam safety conditions. This is often complemented by a large number of instruments read by hand-held computers, thus allowing for a better and more complete knowledge of the dam behavior.

DECISIONS AT THE DAM SITE

Decisions that must be made at the dam site include:

- Detection of the occurrence of an extreme event or of a dam’s anomalous behavior

- Sending warnings to the population at risk and the evacuation of the population at risk

- Notification system

These first three components are generally a responsibility of the dam owner and must be considered in the emergency plan for the dam (Internal Emergency Action Plan ” IEAP). After an emergency event is detected or reported, those responsible for the IEAP must classify the event into a scale of emergency level.

Emergency level classifications are as follows:

- Level 0 – Non-emergency, minor incidents occurring in the dam which do not compromise its structural safety.

- Level 1 – Unusual event, slowly developing, leading to possible discharges (effects in the downstream valley).

- Level 2 – Rapidly developing accident that may compromise the structural safety of the dam; this situation may eventually lead to dam failure and the occurrence of flash floods downstream.

- Level 3 – Dam failure appears imminent or is in progress and cannot be prevented; flash floods will occur downstream of the dam.

For each of these emergency levels the IEAP must provide the following information:

- Define clear descriptions of trigger situations to adopt for each emergency level.

- Provide the specific actions and procedures that must be performed in response to each emergency level.

- Identify the human, material, and technical resources needed for emergency responses as well as allocating the emergency equipment.

- Define the decision chain and identify all persons who act in case of an exceptional or an accident occurrence.

NOTIFICATION SYSTEM

A notification system should be implemented for facilitating communications between the dam owner and the agencies responsible for the dam safety.

The following peoples and groups should be responsible for and involved in the IEAP the notification system:

- The dam operators and the person responsible by the dam

- The dam owner (usually the reservoir operation agency)

- The dam safety authority

- The downstream civil protection services

Flow Diagram of a Fully Automated Data Acquisition, Notification, and Warning System – Click for source

WARNING THE POPULATION AT RISK

The warning system is commonly implemented in the community that is in the most dangerous zone of the downstream valley. Public warnings can be sent through audible systems such as radio and television, door-to-door warnings, and visible systems like personal direct notification via telephone or cell phones (SMS and notification Apps).

Each system has its advantages and disadvantages.4 However, of most importance is to ensure that the message is easily understood by the public and to guarantee that the system is reliable. For this, false alarms must be avoided and maintenance needs to be efficient.

Public warnings using the Internet and the World Wide Web pages of those organizations in order to expand coverage. Billboards also constitute a simple and inexpensive way of warning but are a solution limited in coverage as traditional boards do not allow for up-to-date warnings. However, electronic billboards are now widely used to issue warning messages to those traveling on highways.

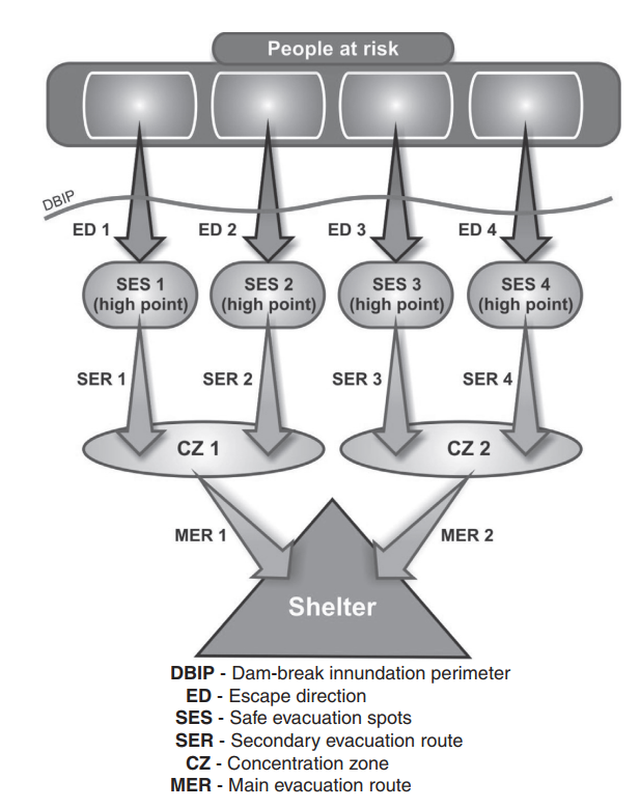

EVACUATION PLAN.

The purpose of an evacuation plan is to relocate people to safe areas whenever their safety becomes threatened, regardless of the hazard. This action implementation is generally the responsibility of the local authorities. A decision should be made to start evacuation either prior to a predicted dam break or immediately in the case of an unforeseen failure. This should take into consideration the celerity of the dam break wave, the distance of the population from the dam, and the reliability of the warning system. In order to ensure efficient evacuations, the nearby population should be educated on evacuation procedures in case of a dam failure. The civil protection teams should also have quality training and there should be an availability of various escape possibilities. Additionally, special considerations should be made for vulnerable persons in affected populations, such as children, the elderly, and disabled people.

CONSEQUENCE OF DAM FAILURE

Flood water can be one of the most destructive forces on earth, especially if caused by an event that unexpectedly overwhelms an existing flood defense or by catastrophic breach of a dam or levee. Decisions on investing in dam or levee improvements are based primarily on risk to life by applying the concept of tolerable risks. Since informed decisions based on tolerable risk require estimates of loss of life for potential flood events, the focus of this section is on estimating loss of life. Estimation of the magnitude of life loss resulting from a flood requires consideration of the following factors:

- Understanding of the population at risk (PAR) in the potentially impacted area.

- Warning and evacuation assumptions for that PAR.

- Flood characteristics including extents, depths, velocities, and arrival time (can be heavily influenced by failure mode and breach parameters).

- Estimation of fatality rates.

Dam failure consequences can be classified as extreme, very high, high, significant, or low. The consequence classification is used to determine the design requirements for a particular dam, with dams of higher failure consequence having higher design standards. In the next section, we explore suggested safety guidelines and inspection procedures for dams falling under the various consequence classifications.

DAM SAFETY GUIDELINES & INSPECTION PROCEDURES

It is helpful to prepare an inspection route in advance to ensure that every part of the dam will be visited. An inspector can take many different approaches to examining a dam, but the selected method should be systematic to ensure that all features are covered and to make the best use of the time available. A recommended sequence to assist with a visual inspection starts at the top of the dam and proceeds downward. Sometimes it may be more efficient to inspect the easiest, or most readily accessible areas first, or those areas of known problems. However, no matter where an inspector is located on the dam or spillway, he should stop periodically and look around 360 degrees to observe other features from that vantage point.

PLANNING A ROUTE

This list provides effective guidelines for routing your visual inspection of a dam.

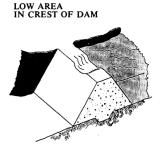

- Dam crest ” Walk across the dam crest from abutment to abutment, observing both upstream and downstream slopes while inspecting the crest surface.

- Upstream and downstream slopes ” Walk across the slopes in a parallel or zigzag pattern along the embankment from abutment to abutment, starting with the upstream slope. Special attention should be paid to the downstream slope below the elevation of the reservoir.

- Embankment-abutment contacts ” Walk the entire length of the embankment-abutment contacts (groin) on both sides of the dam, on both the upstream and downstream embankments (do in conjunction with slope inspections).

- Principal spillway ” Observe all accessible features of the principal spillway and its outlet. Inspect the inlet while performing the upstream slope inspection. Inspect the outlet during or after the downstream slope inspection is completed.

- Auxiliary spillway ” Walk along the entire length of the auxiliary spillway in a back and forth manner.

- Abutments ” Traverse abutments in a practical manner to gain a general feel for the conditions, which exist along the valley sidewalls.

- Outlet works and downstream channels ” Carefully inspect outlet works and reservoir drains that may be present. Travel the route of the stream below the dam to find residences and property that can be affected by dam failure.

- General areas ” Drive or walk along the perimeter of the reservoir and other upstream areas. Carefully inspect all other appurtenant works that may be present at the dam.

DIY EARTH DAM EMBANKMENT SLOPES

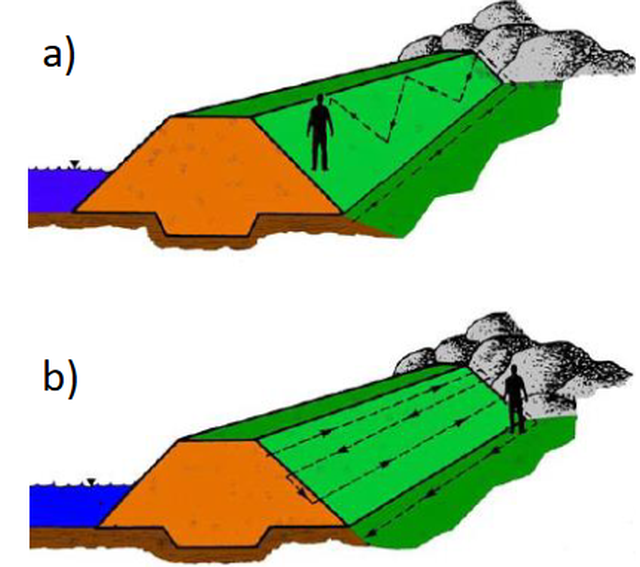

The general technique for inspecting the slopes of an embankment dam is to walk over the slopes as many times as is necessary to see the entire surface area. An inspector must repeatedly walk back and forth across the slope until the whole area has been viewed, giving greater scrutiny to the downstream slope below the pool elevation. The following two patterns can be used for walking across the slope:

- Zigzag ” A zigzag path is one recommended approach for ensuring that an inspector has completely covered the slopes. It is preferable to use a zigzag path on small areas or slopes that are not too steep.

- Parallel ” A second approach is to make a series of passes parallel to the crest of the dam, moving down the slope. It is preferable to use parallel passes on larger slopes or on slopes that are steep because this method is less arduous.

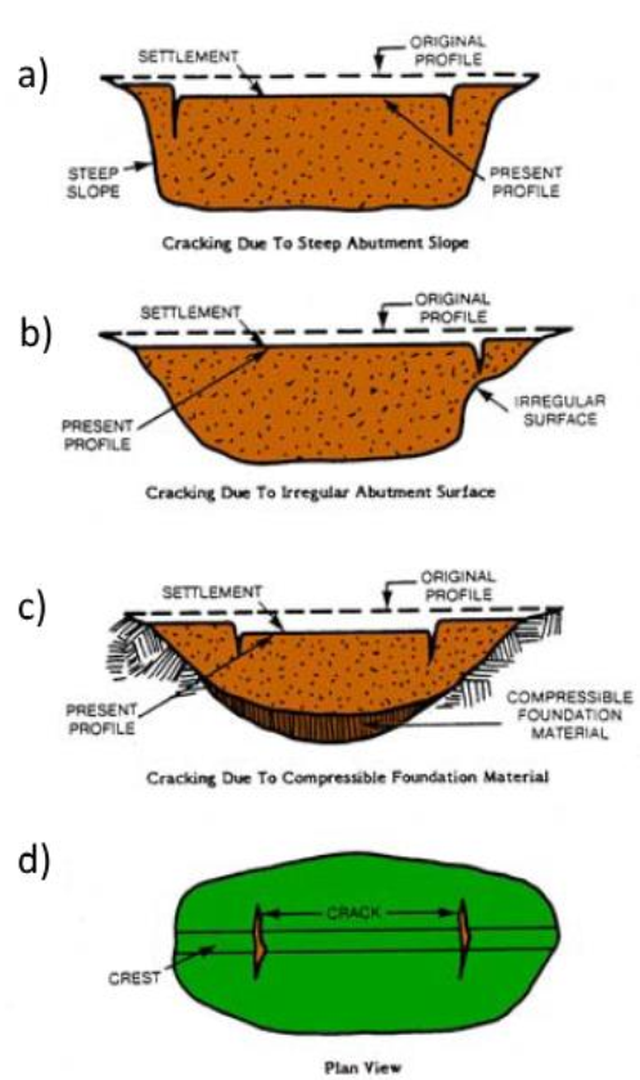

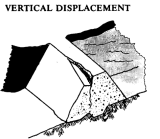

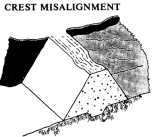

DIY EARTH DAM CRACKS & SLIDES

Cracks and slides may signal serious problems within the embankment. Looking for and spotting cracks may be difficult, particularly if the embankment is covered with heavy brush or vegetation. As a result, an inspector must walk along the slope in such a way that all the cracks will be spotted. Embankment slides are usually easy to find. Cracks in the embankment are often the beginning of a slide and further weaken the soil by allowing more water to enter the embankment. Cracks may be only a centimeter or two wide but 0.5 to 1.0 meters deep. Usually, a depth of more than 0.5 meters means that a serious condition is present. Shallow cracks may be harmless desiccation cracks. All cracks over 0.3 meters deep should be closely checked and evaluated.

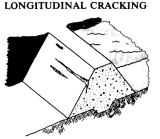

Cracks on embankments are divided into three categories:

- Longitudinal cracks

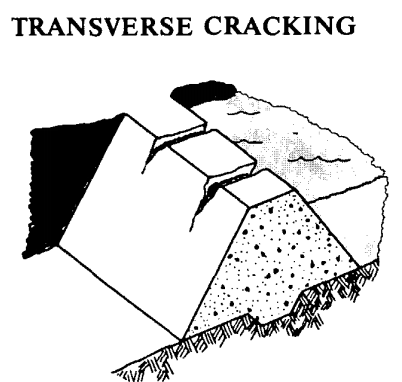

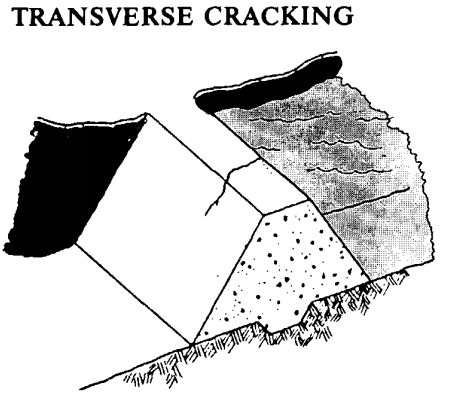

- Transverse cracks

- Desiccation cracks

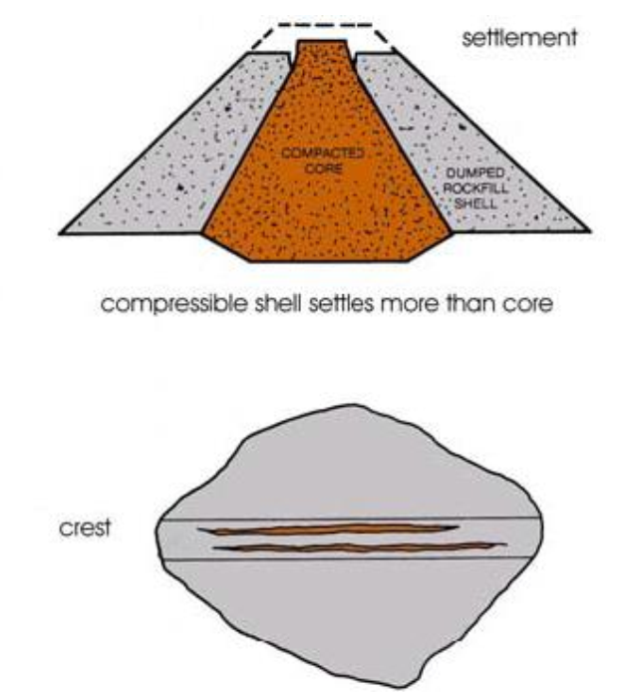

Longitudinal Cracks

Longitudinal cracking may be a sign of localized instability, differential settlement, foundation settlement, and/or movement between adjacent sections of the embankment. In recently built structures, longitudinal cracks may indicate inadequate compaction of the embankment during construction. This form of cracking can occur anywhere on an embankment and is characterized by a single crack or a close, parallel system of cracks along the crest or slope in a direction parallel to the length of the dam.Transverse Cracks

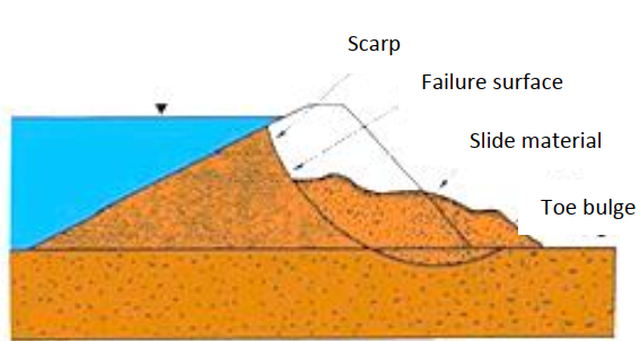

Transverse cracking may be a sign of differential settlement or movement between adjacent segments within the embankment or the underlying foundation. Transverse cracking is usually a single crack or a close, parallel system of cracks which extend across the crest in a direction perpendicular to the length of the dam. This type of cracking is usually greater than 0.3 meter in depth and can easily be distinguished from drying cracks. Transverse cracking poses a definite threat to the safety and integrity of the dam.Embankment Slides

Embankment slides have various names including displacements, slumps, slips, and sloughs and can be grouped into two broad categories:- Shallow slides

- Deep-seated slides

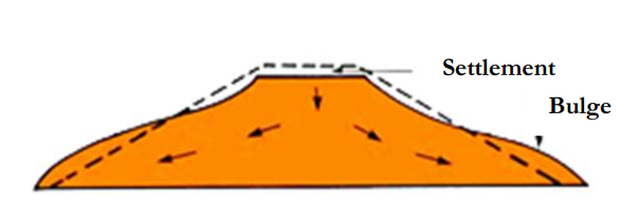

Embankment slides are usually easy to spot and require immediate evaluation by a geotechnical engineer if they are large or are continuing to show movement. Most embankment slides have early warning signs that allow their detection. A bulge in the embankment and vertical displacement at a crack in the embankment are usually signs of sliding.

Bulging of the Dam

Bulging is most evident at the toe of the dam. If an inspector suspects a loss of freeboard (the vertical distance between the maximum water level and the crest of a dam) a survey of the crest should be performed to verify if there has been a loss of freeboard. If this survey confirms a loss, this could indicate a possible dam bulging problem and the probability of dam failure. The area above a bulge should be checked for other indicators of instability such as cracks and scarps. However, not all bulges suggest a stability problem. When the dam was constructed, it may not have been uniformly graded by the bulldozer or grader operator, so there may be bulges in the embankment that were formed during construction. Bulging associated with slides is a more severe problem. If bulging associated with cracks or scarps is discovered, a qualified dam safety professional should be contacted at onceDIY EARTH DAM BREACH FLOOD DETERMINATION

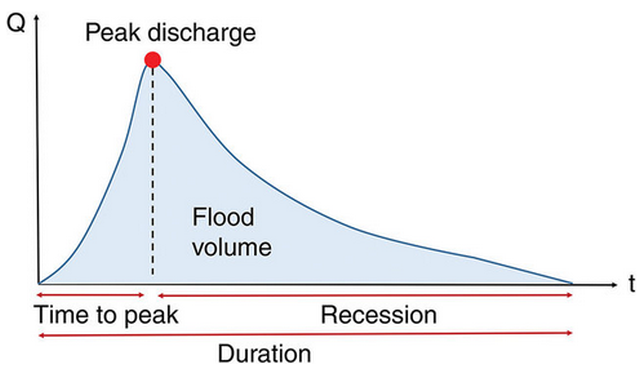

The flood hydrograph (seen below) resulting from a dam breach is dependent on many factors. The primary factors are the physical characteristics of the dam, the volume of the reservoir, and the mode of failure. Characteristics such as dam geometry, construction materials, and mode of failure determine the dimensions and timing of breach formation, volume of reservoir storage, and reservoir inflow at the time of failure; this determines the peak discharge and the shape of the flood hydrograph.

INADEQUATE SLOPE PROTECTION

Slope protection is designed to prevent erosion of the embankment slopes, crest, and groin areas. Inadequate slope protection usually results in deterioration of the embankment from erosion, and in the worst cases can lead to dam failure. Inspectors should look for inadequate slope protection, including eroded and displaced materials and lack of vegetation during every visual inspection.

ESTIMATION OF DAM BREACH PARAMETERS

Dam breach parameters, such as breach width (Wb) and breach formation time (τ), are often estimated using regression equations. These empirical models, derived from historical dam failure data, offer simplified methods to predict breach dimensions and failure timing—critical factors in risk assessment. Commonly used regression equations include those by MacDonald and Langridge-Monopolis, Froehlich, and Von Thun and Gillette, among others. Each regression equation is derived based on different assumptions and datasets, which influences the range of dam sizes for which the equation provides reasonable estimates. If a dam falls outside the range of data used to develop the equation, the resulting estimates may be biased or inaccurate. Below, we present the breach parameter equations developed by MacDonald and Langridge-Monopolis in SI units. For estimates in English units, corresponding figures are provided in the paper.

In 1984, MacDonald and Langridge-Monopolis were successful in relating breaching characteristics of earthfill dams to measurable characteristics of the dam and reservoir. Specifically, a relationship exists between the volume of material eroded (Vm)in the breach and the Breach Formation Factor (BFF), which if defined as the product of the breach outflow volume (Vw) and the height of water above the breach bottom (H):

BFF = Vw (H)

Where:

Vw = Volume of water passes through the breach (m3)

H = Height of water (m) over the base elevation of the breachHowever, before conducting breach analysis, the exact volume of water outflow (Vm) through the breach is unknown. A common approach is to initially estimate Vw as the volume of water in the reservoir at the time the breach begins. This estimate serves as the starting point for the breach parameter analysis. The estimated outflow volume is then compared with the calculated volume from the analysis results. Based on this comparison, a refined Vw estimate is made, followed by a reanalysis and further adjustments. Through this iterative process, the most accurate estimate is ultimately achieved.

Using the calculated BFF, the volume of material eroded in the breach (Vm) can be estimated as follows:

Vm = 0.0261 x (BFF)0.77 for earthfill dams; and

Vm = 0.00348 x (BFF)0.77 for earthfill with clay core or rockfill damsWhere:

Vm = Volume of material in breach (m3) which is erodedUsing the geometry of the dam and assuming a trapezoidal breach with sideslopes of (Zb :1), the base width of the breach can be computed as a function of the eroded volume of material (Vm)as:

Wb = [27xVm – H2 x (CxZb + HxZb Z3 /3)] / [Hx(C + HxZ3 /2)]

Where:

Wb = Width of breach (m) at base elevation of breach

C = Crest Width of dam (m)

Z3 = Z1 + Z2

Z1 = Slope (Z1 :1) of upstream face of dam

Z2 = Slope (Z2 :1) of downstream face of dam

Zb = Side slope (Zb :1) of the breach, Zb can be assumed to be 0.5 (0.5H :1V) according to MacDonald and Langridge-Monopolic.If the calculated breach width is negative, then the reservoir volume is not large enough to fully breach the dam and a partial breach will result. In this case, the head of water (H) needs to be adjusted to estimate the breach depth and peak discharge. Maximum breach widths have historically been limited to less than 3 times the dam height (Fread, 1981). In addition, site geometry often limits breach width.

The time of breach development (τ) in hours, has been related to the volume of eroded material. Interpretation of data suggests that the time for breach development can be estimated by:

τ = 0.0179 × Vm0.36 for earthfill dams

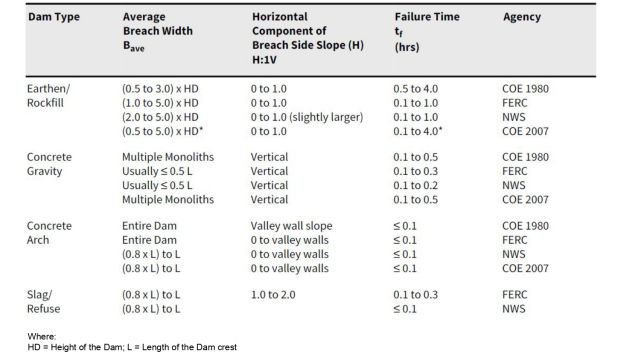

The breach parameter estimation provided by MacDonald and Langridge-Monopolis indicates that their equation serves as an envelope equation, which tends to overestimate breach time. Additionally, beyond their regression equation, several other regression equations derived from various dam datasets can be utilized for estimating dam breach parameters. It is particularly important to carefully examine the validity of parameters for larger dams, as most available failure data pertains to smaller dams. If dam dimensions fall outside the range of existing datasets, regression estimations can become unrealistic. In addition to using regression equations, the breach parameter determination process can be enhanced by incorporating geotechnical analyses and qualitative assessments. It is essential to verify these values against the ranges provided in the Federal Agency Guidelines (as shown in the table below) to ensure accuracy.

Table. Ranges of Possible Values for Breach Characteristics

Table: Ranges of Possible Values for Breach Characteristics

To enhance the reliability of the results, it is essential to utilize parameters from multiple regression equations and conduct a sensitivity analysis. Once several sets of breach parameters have been established, comprehensive physically based computer modeling using HEC-RAS can be performed. This modeling will generate different sets of outflow hydrographs for various study areas, which are crucial for assessing the impact of breach parameters on downstream flood.

For effective risk assessment, it is essential to select the most likely breach parameters for each event or pool elevation, relying on engineering judgment. If breach estimates converge on similar flow and stage values at risk locations, a simple mean value can be used. Otherwise, a more detailed selection process is necessary to avoid skewing results.

Once the final breach parameters have been selected, it is essential to conduct several reasonableness checks:

- Assess the computed peak outflow against peak flow equations to verify consistency.

- Reassess breach size and development time by analyzing breach flow and velocities during breach formation.

These guidelines are based on the 6.3HEC-RAS Hydraulic Reference Manual. For more detailed information on modeling and methods, refer to the “Performing a Dam Break Study with HEC-RAS” chapter of the manual, which offers a recommended approach and includes an applied example.

COMPULSORY COMPREHENSIVE DAM SAFETY REVIEWS

A comprehensive Dam Safety Review (DSR) is a procedure for assessing a dam’s safety as an entirety. This procedure comprises a detailed study of dam engineering with specialist support, which includes an assessment of the records and reports from investigation, design, construction, commissioning, operation, maintenance, instrumentation monitoring, and surveillance activities.

The comprehensive dam safety evaluation should be compulsory in the case of: